3D Search Unlocks Part Database Potential

Using a photograph or CAD file, Physna can search a database of 3D objects to find similar parts. This can streamline engineering and consolidate procurement tasks.

Share

It is hard to imagine the Internet without search engines. In the absence of such tools, users would depend on indexes and personal recommendations for specific website URLs to find content. This scenario sounds like an impossible reality that would diminish the usefulness of the Internet. And yet, many machine shops depend upon out-of-date indexes and tribal knowledge to catalog parts designed and made in-house. The opportunity to forget about past projects that may have incorporated creative solutions to evergreen design problems is one that can impact the profitability and productivity of a shop. While there are many labor-intensive solutions available that require additional manpower, the ultimate solution would be to make a 3D search engine.

This is exactly what Paul Powers, Founder and CEO of Physna, has done. In the system he and this company’s team have developed, a variety of digital formats can be leveraged as input, anything from CAD files to photographs, with the system’s algorithms that the Physna team developed creating a “digital fingerprint” of the 3D object. This fingerprint describes the object and enables the user to search a database of parts using a 3D part as the search term.

The leap from using language to describe a 3D part in a conventional search engine to entering a 3D part itself as the term unlocks aspects of search that the user could not have considered when beginning the search.

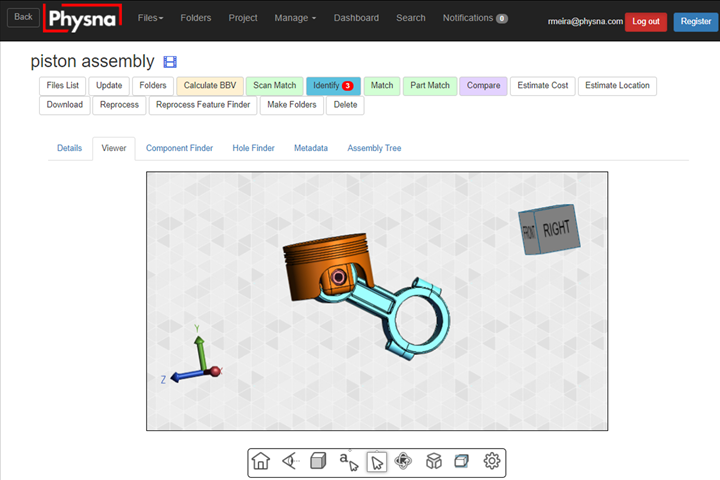

Physna is capable of interpreting assemblies and the parts associated with the assembly. In the 3D viewer, the user is able to inspect the assembly and search for similar parts from the database. Photo Credit: Physna

3D Search Results

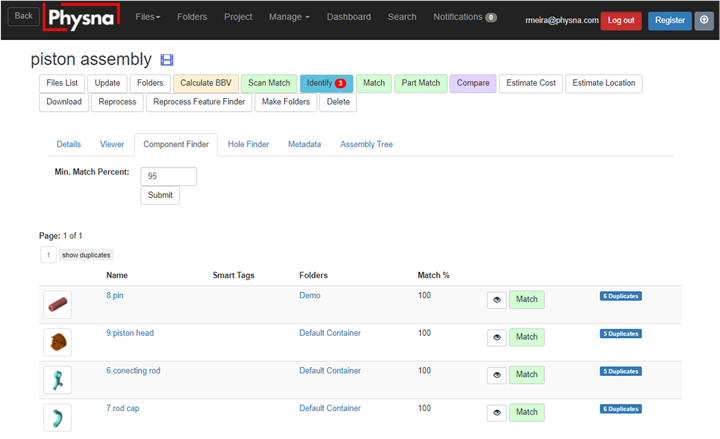

In the absence of this capability, searching for a 3D model is difficult because the process is dependent upon the quality of the search query and the way that the part is described in the database. If a user is not able to describe the part with the same language with which it was added to the database, it is not likely that the user will find the right part. As Powers notes, the problem is eliminated when using Physna because language is not the primary form of search. “We deliver results that are derived from geometry, not language,” he says. The power of this is potentially realized if a business such as a machine shop moves all of the parts that it has ever modeled into the database. Once this process is complete, the software is able to match parts that are not only 100% matches, but parts that are similar or share a certain percentage of geometry.

Physna is able to locate components of a piston assembly with 100% confidence. The match percentage diminishes as variations of the part are found, pointing the user to alternative or similar parts. Photo Credit: Physna

For instance, if an engineer at has modeled a flange that features a 1-inch ID, a common search using language would be “1-inch flange”, but if the engineer uploaded the model to Physna, the fingerprint would include aspects of the flange like its bolt pattern, whether or not it incorporated a bearing and contours of the flange design. This may lead to discovery of previously designed parts or even compatible third party parts if the database is connected to other vendors.

Using the Data

Powers sees many integration options for the software. Many of its functions can be used through APIs that bring the cloud data into custom-built applications or with software that a shop is already using like ERP or PLM. Developing these software integrations is a priority and additional APIs are being rolled out continuously, he says.

Once set up, and once all 3D files are loaded into the software, a shop will start obtaining useful information quickly. Physna will run a duplicate part report that identifies parts that are exact matches and parts that are similar. “We find that companies save, on average, 40% on procurement costs,” Powers says. This is because many companies are not able to fully streamline ordering, so redundant orders are inadvertently made.

This same information can highlight parts that have been previously designed and can be adapted or reused for a new application. This type of information is especially valuable for job shops and contract shops, particularly as turnover and retirement creates gaps in institutional knowledge. Even a partially designed part might trigger Physna to detect a match in database because the digital fingerprint matches parts based on all aspects of its geometry.

The technology in Physna can also accelerate part identification. The shop can search its part database with a single photograph. Physna converts the 2D image into a 3D model using its algorithms and can associate the 3D model with a part that had been previously uploaded with a high degree of confidence.

Bigger than a Single Shop

When granted permission, Physna is capable of reaching external sources to enhance search results. For example, OEMs can source alternative suppliers for parts if multiple vendors opt into an arrangement that would enable visibility to the OEM. This streamlines supply chain sourcing and allow suppliers to market their services to new clients. While this is not a new concept for the industrial market, the process to begins with a single photograph on a shop floor with instantaneous results. Powers says he looks forward to the day when this technology might become a standard feature in shop management software.

Related Content

The Power of Practical Demonstrations and Projects

Practical work has served Bridgerland Technical College both in preparing its current students for manufacturing jobs and in appealing to new generations of potential machinists.

Read MoreHow to Mitigate Chatter to Boost Machining Rates

There are usually better solutions to chatter than just reducing the feed rate. Through vibration analysis, the chatter problem can be solved, enabling much higher metal removal rates, better quality and longer tool life.

Read MoreTips for Designing CNC Programs That Help Operators

The way a G-code program is formatted directly affects the productivity of the CNC people who use them. Design CNC programs that make CNC setup people and operators’ jobs easier.

Read More5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreRead Next

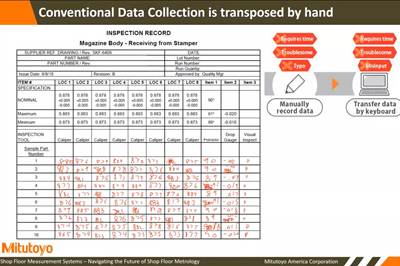

Implementing Digital Shop Floor Metrology

In a recent webinar with MMS, Michael Creney, Mitutoyo America’s vice president of product management, outlined the benefits of digital shop floor metrology and delivered tips for adopting it.

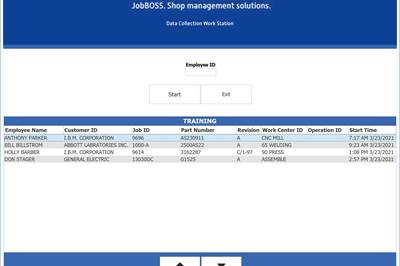

Read MoreERP Becomes a Communication Tool

Enterprise resource planning software modules provide at-a-glance understanding of job priority and location between departments as pandemic restrictions disrupted collaborative working environments.

Read MoreMeet the Automation That Makes Machine Tool Automation

A new manufacturing cell at Mazak’s North American headquarters is one part machine tool production unit and one part demonstration facility. And it’s here to provide a lesson about how automation can tackle skilled-worker shortages and supply chain issues at the same time.

Read More