Share

Hwacheon Machinery America, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Takumi USA

Featured Content

View More

- Steve Kline, Chief Data Officer, Gardner Business Intelligence

- Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT)

- Andrew Crowe, Advanced Manufacturing Technology Instructor, Ranken Technical College

- Harry Moser, Founder and President, The Reshoring Initiative

- Robert Atkinson, President, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF)

- Scott Smith, Group Leader, Intelligent Machine Tools, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Peter Zelinski: Welcome to Made in the USA, the podcast from Modern Machine Shop Magazine exploring some of the biggest ideas shaping American manufacturing. I’m Peter Zelinski.

Brent Donaldson: I’m Brent Donaldson. And you have made it to the feel-good hit of the summer — season one’s final installment for Made in the USA, a series that tackles big-picture topics in manufacturing. And in light of today’s theme, I think it’s worth quickly mentioning how this series took shape well before anyone had ever heard of COVID-19.

Pete: After working through the concept for this show back in January of 2020, we began reaching out to a lot of people who worked both inside and outside of manufacturing. We talked to machine shop owners, manufacturing business and trade executives, but also economists who specialize in topics like automation, global supply chains and skilled labor issues.

Brent: During this period, a lot was changing in the world that Modern Machine Shop covers a decade after the 2008 recession, U.S. manufacturing employment and productivity numbers were steadily rebounding. Machine tool consumption — a strong indicator of overall U.S. manufacturing health — was on the rise again. Trade shows like the International Manufacturing Technology Show were booming, and the year 2020 began full of optimism for the future of U.S. manufacturing and the independently owned machine shops that form the heart of this industry.

And then, well, you know what happened next.

[covid-19 news clip mashup]

Pete: We, like everyone else, had to adapt. Everything about the way we work changed. For us, that meant no more traveling for story interviews, and the topics we covered were much more likely to be about the emergency manufacturing of medical equipment and PPE rather than the latest developments in CNC five-axis machining.

Brent: But something else emerged from the early days of the pandemic, something that breathed life into this project, which seemed destined for the back burner while the pandemic raged: Americans suddenly became much more aware of — and interested in — our supply chains and manufacturing at large. To be clear, there are experts on supply-chain related topics who were not at all surprised by what happened at the onset of Covid-19. But before the pandemic, it was inconceivable to many of us that the world’s wealthiest nation could run short on critical medical equipment, not to mention household staples like tissue paper, cleaning supplies and other items. And what we realized was that we were already talking to experts about these topics. We realized that the kind of reporting we were doing — and the way we were doing it — was the very thing we should be doing, and at the right moment.

Pete: Which is our maybe not-so-humble brag that brings us to this episode, the final episode for season one, that we’re calling “The Way Forward.” So far, we’ve been looking at system-wide effects of things like broken supply chains, automation, skilled workforce issues and our perception of manufacturing jobs — examining each topic through a prism of individual experiences. So let’s start with a big, system-wide question and bring it back to personal perspectives now: Is there today a new dawn, a new moment for American manufacturing?

Brent: The supply chain reckoning, and the rethinking of supply chains that came as a result, did not represent a rock-bottom moment. It was the culmination of a turnaround already underway — a change of viewpoints about manufacturing that started well before the pandemic. It was not so much a radical departure from the status quo, but an acceleration of changes that were already in motion. As we said, a different way of thinking about U.S. manufacturing had already begun.

Steve Kline: My name is Steve Kline. I'm the chief data officer at Gardner Business Media, part of a family-owned business. I've been doing forecasting and market analysis and market intelligence for the company since 2007.

I think one of the big things that's been happening over five or seven years for sure, is there's a wave of populism happening not just in the United States, that's happening in every country around the world. Essentially, this wave of populism is people wanting to do more in their own country, manufacture more in their own country, or at least their region. So manufacturing more in North America, for example, for the United States.

There’s a trend of that happening, I believe, for the last five or seven years or so. A lot of this is the pendulum swinging back and forth. And if we go too far, one way is “we're going to offshore our manufacturing, and we're going to do things overseas, and we're going to import everything.” But now the pendulum starts swinging back. And people are like, “that's not such a good idea.” In particular, I think for the average American who's not in manufacturing, I think 2020 — in the lockdowns and the disruption in the supply chain — really brought that home to people that like, “wow, we need to really put an importance on manufacturing and understand that we make stuff here.” Most people don't ever even think about what they're buying, and where it comes from. Not even the final product, all the inputs that go into it, where they come from, and that, during the sort of medical crisis of last year, we're having to come up with all these medical devices really quickly and, well, there's only one company that makes that and they're in Puerto Rico and they had a hurricane destroy their facility.

Doug Woods: Also, take a look at Silicon Valley —

Brent: This is Doug Woods, president of AMT, the Association for Manufacturing Technology.

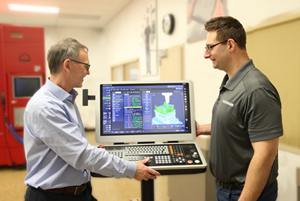

Doug: — it was all “let's just make software with computers.” There's a lot of cool things going on in Silicon Valley, when you're talking about this type of transformative technologies, a lot of this fueled by a lot of the cool innovation coming out of that particular part of the country. And all of a sudden, a lot of those people are, “Hey, you know what, I just don't want to make something that's — ” in this case, I use the word virtual — “I want to make a physical thing. I want to make a machine, I want to make a robot, I want to make a drone, I want to integrate my cool technology into those products. So, suddenly there's an entire group of people coming out of that space, jumping into manufacturing, where manufacturing is cool, and they're developing the next iteration. And they're asking, “why do I put G-codes and M-codes into a machine to talk to it? Why can't I just talk to the machine? Why can't I just program in English and have it do what I want? Why can't I just move it around to what I want? Or send it just a picture of a part I want to make, a new machine, and figure out how to make it?”

I mean, the things they're thinking of because they're asking the question, “Why do it that way? Why don't we do it this other way?” That's driving an entire set of the next gen of things.

Along with that, there's a venture capital market that all of a sudden is following those folks going, “Hey, you know, maybe there's a lot of investments we should be making. There's cool things that people are developing, and also there's a VC spectrum. I want to invest in these so I'm not looking for the 92:1 multiple of the you know, next potential Twitter or Facebook. What about a lot of the people in the space of doing cool things in manufacturing, that could be the next new great, billion-dollar robotics company, next billion-dollar additive company, billion-dollar drone, fish, et cetera.”

All those things have huge levels of momentum that are driving where manufacturing technology goes in the next 20, 30 years. Autonomous vehicles — you know this whole change to EV, electronic vehicles, autonomous vehicles integrating some aspects of manufacturing technology into our transportation and mobility systems, that's bringing all these different aspects, all these different needs, all kind of combining at the same time to make manufacturing cool. And the coolness is becoming commonplace for young kids and parents to talk about, and for four-year universities and community colleges to teach, for people to invest in and therefore it drives the industry. That's why it's exciting now.

Andrew Crowe, instructor of advanced manufacturing technology at Ranken Technical College.

Andrew Crowe: So, manufacturing was never on my radar.

Peter: This is Andrew Crowe, instructor of advanced manufacturing technology in Ranken Technical College’s Precision Machining department. We’ll learn more about Andrew in a but, but his path into manufacturing and CNC machining reflects the challenges that machine shops face with recruiting young, talented people. Now, he’s turned the lessons he learned into a model of recruitment for younger generations.

Andrew: It was never something that I even ever considered was happening in the world, let alone for a job or a career. I didn't come from a family that really had any manufacturing DNA, like we didn't have Bridgeport or anything in the garage. We didn't have a garage.

You know, there was nothing around me that I could look at and say, “okay, that's manufacturing.” I never really considered where the things that I bought from the store came from. I knew about assembly lines, I knew about plants, like, you know, Chevy plans and stuff like that, but I didn't actually think about how the parts that they were putting together were made.

Brent: You know what, let's pivot to that for a minute. Let's talk about — using your experience and the path that you took to talk about deficiencies in the way that we steer young people toward this career or that career or toward this type of education versus that type of education? Like, what are the issues that you're seeing, that you saw back then, that you're seeing now? And also, how are things changing that maybe give you some hope as far as all this goes?

Andrew: So when I got in to the industry, there was an overarching view of experience, of no experience over schooling. At that time, it was because a person with no experience was able and more willing to learning the systems in the procedures of that particular manufacturing plant or factory. With schooling, I think, for a long time, the schools weren't teaching things that were aligned with the industry at the time. Students would graduate from these programs, and then they wouldn't be prepared to actually work in the industry, the way that they needed to be impactful for these companies, because they'd be stuck on the old systems, or what the school taught them, and not what the industry needed them to know to be effective at the time. And I think because of that miscommunication, there was a long time where industry didn't want to hire or didn't have faith in what the schools, the technical programs were turning out, specifically in manufacturing. Manufacturing got a problem of adapting.

So for a while, when I was in the industry, even when I was at the point where I was hiring people, it was kind of an unspoken thing, like, they call them book boys. “Don't hire a book boy, unless you need to get somebody that learned from the Grandpa, or that has some experience some kind of way. But if they're fresh out of school, we cannot afford it.” So, at least in my region, in the Midwest, and in the South, that's kind of how it was. I think that because of that, enrollment in the tech schools, and these programs, slowed down — faith and trust in the tech schools, and these programs, just kind of went to the wayside.

Also compounding with that, a lot of work left America. That took place over generations from the ‘80s, definitely when I was young, through the ‘90s into the early 2000s. It just got more and more where things were outsourced. So there were kids like me, who grew up in the 80s, who had no idea of what manufacturing was because I didn't see people manufacturing, I didn't see a bunch of machinists going to work every day. It wasn't something that was visible for me. It wasn't something that was actually — "who cares where things came from?” I didn't know. Car parts just pop up where they pop up from, you know?

What I see changing these days is this: the tech schools that are still pushing advanced manufacturing, and do still have good programs are because they're invested in the communities, and they're actually getting out there and showing what the industry has to offer. They're also making it more accessible and more affordable to come to these schools.

Pete: Harry Moser resonates with this. He’s the founder and president of The Reshoring Initiative, consulting with American companies looking to perform their manufacturing in the U.S. In line with that, he thinks about what a long-term shift to greater domestic manufacturing will require.

Harry Moser: I agree, 100%, that recruitment is the biggest problem with a skilled workforce. If there were smart, disciplined kids lined up at the high school, in the community college wanting to study manufacturing, there'll be programs from the schools and community colleges respond. So the problem is recruitment.

I think what you described is that most people don't — most people understand plumbing and electricians, because they see them happening in their home, whereas they don't see manufacturing happen in their home. Therefore, you have to imagine “what is manufacturing?” and then manufacturing can be putting something into a multitasking machine and making it do something very complicated or it could be chemical, it could be wire harness or steel. Manufacturing is very broad.

Again, nobody sees it. And if they hear about it, or see it on the news, it's almost always because of a safety issue or pollution or discrimination or something horrible, like they are shutting down and jobs are being lost. So I think the funny thing is that manufacturing should be the most tangible thing, because when you do the work of an electrician or plumber, you haven't created anything in a sense. When you do manufacturing, you come out with a shiny, accurate, detailed piece of metal of some kind that gets used for something goes in a satellite, goes in a car, does something. It should be the most tangible, the most obvious, most rewarding, but since the kids never see it, they can't appreciate the benefit of manufacturing.

Let me just say one more thing on that. Another reason that recruitment doesn't happen is that for the last 30 or 40 years, people have seen job loss in manufacturing, significantly due to offshoring. They know their uncle or their brother, or somebody lost the job at the mill, is now working at Walmart or something. So they say to themselves, “Wow, manufacturing wasn't able to take care of my relatives, why should I think it'll take care of me” That's why we emphasize the importance of documenting and promote the success of reshoring, so that the students and the guidance counselors say, “Yeah, Susie, you want to become a welder? I think that's great. There's always a shortage of welders, and manufacturers are coming back to the US, even coming back from China and India. So yeah, why don't you become a welder? And, Bill, why don't you become a tool maker?” That's a great idea as opposed to “Well, I wouldn't do that.”

Brent: So here we are. The wrong-headed thinking that the United States can be the creative innovator who conceptualizes and designs things while offloading production to low-cost countries — that thinking may finally be disappearing. As Andrew points out, we need to tackle manufacturing’s awareness issue in order to provide a skilled workforce now and in the future, because all signs seem to indicate that the prospect for American manufacturing, at least in the near term, is positive.

One way to tell? Wall Street is paying attention.

Steve: The design and the creative aspect that we pride ourselves on in America, the idea that we don't need a manufacturer, I think we're realizing the effect of separating that. Manufacturing and design and idea creation really go hand in hand, and you lose something when you move those far apart from each other. And not only that, we're realizing that shipping all these goods is expensive, and a big part of the supply chain disruption right now is because the ports are backed up. Then we have the Evergiven in the Suez Canal blocking boat traffic through the Suez Canal for several days. Just the length of time that it takes to ship goods around the world dramatically impacts the supply chain.

I think everybody is beginning to rethink that. In particular, over the last year or two, I started to read a lot of articles from people on Wall Street and the finance industry talking about these very issues of supply chain and the need to invest in manufacturing. And once they start talking about that in all of their investor calls, quarterly calls, all that kind of stuff, they're going to be putting pressure on companies to reinvest in, in production at home. So it's just bound to happen.

Of course, we notice it's already been happening for a decade or so, when we look at machine tool consumption. Over the last 10 years, the US has been increasing its share of global machine tool consumption since 2010, gone from fourth or fifth back up to second in the world and narrowing the gap with China. The US is now around 13%, and China's about 30% of global machine tool consumption. There's already been this shift over the last decade, and production just tends to follow where machine tools are being consumed.

Peter: The ascent is happening, and it’s been happening over a long period of time. As we’ve explored throughout this series, manufacturing needs leaders who take a long view — who invest in automation and new technologies not only to stay competitive with low-cost foreign competition, but also to be competitive in recruiting talented, technology-focused employees. But the reality is that even though we are climbing out of a catastrophic global pandemic that exposed the vulnerabilities of offshoring with lean supply chains — it can be hard for companies to resist the cost savings that offshoring can provide or seem to provide. The market might drive them to the short-term view. So here’s a question: can the United States government help?

Robert Atkinson: Yeah, I mean, that's obviously a big complex question.

Peter: This is Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

Robert: But let me give you two simple answers. Fully loaded German labor costs, if you include health care, and retirement and wages and all that stuff is about 40% more than US labor costs. So when US manufacturers say, “Oh, our labor costs are too high” or whatever — not compared to Germany, they're not. And yet, until recently — and it still may be true, I haven't looked at in the last year or two — but for a long, long time, Germany was running a trade surplus with China. We were running a trade deficit with manufactured manufacturing with China. So they have higher costs and yet they're able to be globally competitive. How did they do that?

Well, part of it is that there's two things I think are important there. One, I met with some German CEOs a while back from manufacturing. And I said, “How come you guys don't offer more to China?” And they said, “Look, don't get me wrong. Don't get us wrong. We're private manufacturing, we've got to make a profit for our shareholders. We do offshore some things to China. But our first response, when we see that we have to meet the Chinese prices, we have a hold a meeting with our engineers, and we say, ‘Okay, are there things we can do?’ And what would they be for us to be able to become more productive and more innovative, to be able to compete with somebody who might just go to China?” In the US, the response tended to be, “Oh, let's go to China. Let's just move.” And the German companies were more willing to say, “Wait a minute, should we invest in some new machinery and maybe train our workers?” So there was more of an attitude of the CEOs there to look a little bit longer-term than just a quick fix of “Oh, we’ve got to get our cost down. So let's move to a low wage place.” That's an important factor.

The second important thing here was that the German government simply had better policy. I'll give you an example. In the United States, we have a very good program that's been run for years by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which is a government lab that works with industry. It's called the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, and it's about 60 centers in all the states. It's not staffed by government bureaucrats, but staffed by guys and gals who are in manufacturing facilities, engineers and technicians who go out and help small manufacturers adopt the latest and best technology. Well, the German program is 20 times bigger than ours. On a per GDP basis it’s 20 times bigger. The Japanese program, the equivalent of what they do is 40 times bigger than we do. At the end of the day, manufacturing firms, their owners and their leadership are going to have to take on this challenge — and they are, but there's no reason government can't help tax credits for new equipment. With these manufacturing partnerships, we could be doing a lot more to help our manufacturing firms fight the global fight.

At the end of the day, we can't and should not want to compete in manufacturing on low wages and low skills. The only way for us to win in manufacturing is what you could call the high-road strategy. So as employers, really spending the right amount of money on new and updated machinery and equipment.

Brent: Earlier, economist Steve Kline talked about US machine tool consumption as a general measure of the health of US manufacturing. If we are going to collectively decide to take a high-road strategy in this country when it comes to investment in manufacturing technology, how much room do we have to grow? How big is the gap between the machine tool activity we sent to China versus what is possible to bring back to the United State?

Steve: Generally, when you look at where production is happening in manufacturing, you've seen an investment in machine tools prior to that shift in production around the world. Machine tools are needed to make all the metal parts for cars, airplanes, refrigerators, TVs, all the stuff that we're used to using. They're also needed for plastic processing industry, because almost all of that needs a mold, and you need machine tools to make molds. Without that investment in machine tools, and it's hard for any economy, any country to grow their production and manufacturing.

So you see this investment in machine tools happening before production shifts start to happen. Over the last 20 years, we've seen significant changes in machine tool consumption globally, the from 2000 to 2010, we saw the US slowing and falling in its share of global machine tool consumption from roughly 17% to about 6%. We saw China on an incredible increase from 5% to 40% over that same time period. Since then, we've seen those trends reverse. From 2010 to 2020, China went from 40% of global machine tool consumption down to 30%. The US went from 6% up to about 13%. These are decades-long trends that we're looking at.

Given everything that we've talked about, and the supply chain issues and populism and all that, I think there's still more room to go for the US to continue to increase its machine tool consumption and continue to increase its production overall and bring more manufacturing back home, because even though we've increased to 13%, and nearly doubled our share of global machine tool consumption since 2010, we're still below what we were in 1998, when we were around 17%. If you go farther back than that, the US had a higher share of global machine tool consumption, since a lot of the countries that are manufacturing now weren't really manufacturing at all 30 or 40 years ago. There's still plenty of room to increase manufacturing and invest in manufacturing.

Peter: Let’s bring this full circle. Investing in US manufacturing and increasing output through technology is going to require people. Young people will need to be made aware of what manufacturing is — and isn’t — and find a way into the pipeline of high-tech jobs that will keep the US production engine running. We heard a little bit about this challenge from Andrew Crow, whose path in this field was not only difficult to find, but fraught with challenges once he started down that path. One issue his story highlights is the question of how we include all of the talent available to us in meeting manufacturing’s future needs.

After graduating from college with a political science degree right at the beginning of the Great Recession, jobs in his chosen field were basically nonexistent. So, with two young kids and nowhere else to turn, Andrew took a third-shift job cutting material at a machine shop where his friend’s mom worked.

Andrew: I was in charge of cutting all the material for the hot jobs in the morning and dropping them off at the workstations — the cells — with three lathes apiece. And, you know, it’s third shift, you're by yourself, so there was nobody there. I just got to--you ever seen that movie where the guy gets locked in the museum and then like everything comes alive? Yeah. It was like that. I had never been exposed to anything like that, and I was by myself. So, as I'm dropping off material, and I had my headphones in, I'm walking around to these different machines, and I just like a kid in a candy shop. But I was too scared to touch them.

It's like, “I want to know what this does, what are these things that they're making here?” I was looking at these raw barstock that I'm cutting, and then dropping them off. And then I was curious, like “what do they do with this?” “How is this a business?” So I was about a month in, my curiosity got to me, and I hung around after I clocked out, end of first shift. I started watching the people that were coming into the parking lot, they had new cars. The first time I ever saw a Ducati was from a guy that was a machinist there, and they were talking about their lake houses and stuff. And I asked, “Aren't you guys watching the news, everybody's walking away from their mortgages, and the economy is crashing.”

It was just another world, and it felt safe. It felt new and exciting, and it felt like it was gonna be here, and it had been here for a long time. A fire lit under me, and I would start making that a habit, staying over in the first shift. Nobody liked me, and nobody wanted to have me around for real. But I didn't care. I just wanted to learn. You know, for different reasons, the whole old school, new school situation that we still have in manufacturing today. It's hard to get accepted by the old school, but they’ve got all the great knowledge and stuff. The new school, we have some awesome ways to innovate, and we have great ideas, but it's hard for us to get hurt.

So, same shop dynamics, I dealt with it. I didn't want it to stop me because I really, really wanted to be in this industry, whatever it was. So, I started buying coffee and donuts, and there was this one guy that worked in the manual department. He was a Polish gentlemen. He told me that if I bring him the doughnut box first, he'll let me take notes. That was our deal.

So I got in, and I would stay after like, four hours a day, off the clock. Mind you, I was in graduate school at the same time. Plus, I had a young family. And, I just made it happen. I took as many notes as I could, that was the deal. I’d bring him the box first, be quiet, stay out of the way, get what I needed to get and took good notes.

The job that they did there, was they made non-contact bearing isolators. What he would do was, he would do any of the hand turning or opening of bores when people sent the isolators back because they had lifetime warranties on them, so he would do a lot of the reconditioning on the manual lathes. And he would tell me why he was doing it. He was like, “Kid, this is a dying art.” He didn't say this is a career, he called it an art. That stuck with me — he was like, “if you learn this, you learn this art you're going to be rich forever.”

Brent: A couple of years ago, a friend of Andrew’s dubbed him the leader of the new American manufacturing renaissance—a title that stems from Andrew’s passion for manufacturing and his ability to relate his experiences in the field to young people who, much like Andrew just a year years ago, don’t know enough about it to consider a career in manufacturing and CNC machining. Now in a leadership position at Technical College’s Precision Manufacturing department, here’s how he is trying to modernize an outdated model — and culture — for working in high-tech manufacturing jobs.

Andrew: There are conversations that I've had with people in programming rooms, and they're like, “Don't start teaching Mastercam until kids are in their second year in college. Because it's too robust, and they'll never know how to do it.” And we didn't start bringing people into the shops program room until three- or four-years in. Well, if we hold on to that, we're going to start only hiring programmers at 25 or 30 or 40. We're cutting off a lot of their time that they've had to innovate. You're taking 10, 15 years off of an employee that you could have hired at 18. What I'm saying with that is kids grow up with all of the things that were hard for us to get right. Our kids, especially right now in a pandemic, our kids have been on the phone, touchscreen, iPad, they've been on computers, they are digital children, they are highly able to do all of these things that we're going to be doing in industry 4.0. We've got to cultivate that, make that a good thing and not a bad thing because that those are the skills that are going to move us forward. As everything automates, it's going to beget new jobs. It's going to beget jobs that we don't even understand.

There's a kid out there right now that can be on his tablet or his phone, making Mastercam models in SolidWorks. He could be modeling, he could be dropping programs and Mastercam for five different shops and just sending them digitally, the programs and taking calls, you know what I'm saying? Like, that's a real job that will be coming up in the future, there's going to be a guy, there’s going to be a kid that is going to be having five different, computer screens up in his basement somewhere. On one, he's going to be playing Call of Duty, on the other one, he's going to be monitoring, a third shift with robotic arms, watching for data and efficiency on when to change out tools. On another one, he's going to be looking at different chip mills and coatings on end mills, to see what's going to run even better.

These kids are already built for this. These kids are already looking at multiple screens, doing multiple things at the same time. But we're telling them that those things aren't coveted. Because the old guard who is doing the hiring and that get the people quote, unquote, “interested,” they don't know anything about that. They don't know, they can't foresee what it's going to look like, and that these skills that they're doing are very coveted and needed. So we’ve got embrace all of these things that the kids are doing, and allow them to actually give positive input. And then we have to take it.

It's a double-edged sword, and then at the same time, it's authenticity with the kids. Like, there's a lot of kids that have been ousted or told that they weren't good enough, or told that because they come from certain neighborhoods or look a certain way that certain fields aren't for them, or certain things aren't for them. And that's simply just not true. You know what I'm saying?

Like, I'm all of those things, I look like the rapper, or I look like the guy on the block that was maybe doing the wrong things, but I am who I am now, so you can see the whole transition. Kids, if you don't have a mom or don't have a dad, if you don't see a way out, you can see that in me, because you can see that I didn't have to change who I was, I didn't have to do any of those things to be successful in this field. I tell them “You can do it, too.” And they believe it. I'm here for all that.

Peter: The opportunities for US manufacturing are perhaps greater than they’ve been in decades. The challenges we face trying to take advantage of those opportunities are also very real. “But we’ve done it before,” says Scott Smith from Oak Ridge National Laboratory, “and we can do it again.”

Scott Smith: I don’t think it’s such a monumental task, I think there are plenty of examples in our history where we decided, “This is important, and it’s something that we’re going to work on.” And the change happens surprisingly fast.

I talked about numerical control earlier. Certainly, that happened fast, and it required people to rethink machine tools altogether. It required them to learn new skills that they never had to learn before if they wanted to still have a job. They had completely different jobs than what they had before. But the change happened really fast. Now, you'd be hard-pressed to go into a machine tool maker in the EU or into a factory in the US where there's not a numerically controlled machine tool. I mean, it happened, it actually happened.

You know, it wasn't so long ago that the idea that you order everything that you need by hooking your computer up to a cable connection would have been unthinkable. Now it's almost unthinkable not to have it that way. So, I don't think we're talking about changes that are that dramatic, but we have to decide that manufacturing is important to us.

Peter: “We have to decide manufacturing is important to us.” That’s a statement we want to go out on. We’re going to leave you here for now.

We want to thank everyone who spoke to us, and we want to thank our sponsor, Hardinge.

Brent: And finally, we want to think The Hiders for letting us use this great song, which, now that I think about it, I don’t think we’ve ever played in full, so thanks again for listening, and here you go!

Related Content

Can AI Replace Programmers? Writers Face a Similar Question

The answer is the same in both cases. Artificial intelligence performs sophisticated tasks, but falls short of delivering on the fullness of what the work entails.

Read MoreGenerating a Digital Twin in the CNC

New control technology captures critical data about a machining process and uses it to create a 3D graphical representation of the finished workpiece. This new type of digital twin helps relate machining results to machine performance, leading to better decisions on the shop floor.

Read More6 Machine Shop Essentials to Stay Competitive

If you want to streamline production and be competitive in the industry, you will need far more than a standard three-axis CNC mill or two-axis CNC lathe and a few measuring tools.

Read MoreTips for Designing CNC Programs That Help Operators

The way a G-code program is formatted directly affects the productivity of the CNC people who use them. Design CNC programs that make CNC setup people and operators’ jobs easier.

Read MoreRead Next

Made in the USA - Season 1 Episode 5: Succession - A Family Machine Shop Story

The story of Geno and David DeVandry reflects the sea change in machine shop ownership facing this country as baby boomers reach retirement age. The change in leadership from father to son at their family-owned machine ship required a new mindset, a new way running the family-owned business, and that one generation let go and allow a new one to step in.

Read MoreMade in the USA- Season 1 Episode 1: How We Got Here

Episode 1 of Made in the USA Podcast examines manufacturing issues related to trade policy, global supply chains, education, automation and our ability to produce skilled workers.

Read MoreMade in the USA - Season 1 Episode 4: Making the Case for Manufacturing

The majority of Americans want to "bring manufacturing back" to the U.S. The problem? Many of these same people do not want their children to work in manufacturing because of outdated beliefs about what a machine shop looks like.

Read More