CNC Machines, Wyoming Monks, and Enduring Works of Gothic Art

The Carmelite monks of Wyoming adopted CNC machining to help build a monastery that, without this technology, would take decades or longer to complete. How they are doing it is fascinating. But so is why.

Share

Autodesk, Inc.

Featured Content

View More.png;maxWidth=45)

DMG MORI - Cincinnati

Featured Content

View More

Here is a story about how an unusual article came to be. If you’ve ever wondered how and why the writers for Modern Machine Shop choose the stories we publish — specifically atypical stories such as this month’s cover feature — read on.

The editors of this publication devote our working lives to reporting technological innovations and applications in the industrial domain of metalworking. What we do not do, or rarely do, is examine for whom and why these technologies are being applied. We reference the end markets that destined for machined parts because this is relevant information for any number of reasons. But going beyond that — focusing regularly on the end-use of discrete parts — would not only change the nature of our mission, it also would bring into serious question our utility to you.

Still, every now and then, it can be useful and just plain interesting to step back and see what all the fuss is truly about. What greater good results from these mountains of machined parts? Who will benefit from them, and how?

The holiday season, traditionally a time to reflect and give thanks, felt like the right time to consider such frivolities. But another reason presented itself, just recently, in the form of a brief comment on LinkedIn.

“This is really cool,” began the comment that led to this reporting. He was referencing an article I had written several years ago about an Amish-owned machine shop in Northern Indiana that ran several automated Swiss-Type CNCs. “You might want to check out what these monks are doing in Wyoming with CNC,” he said.

And so, at the risk of backing myself into a reporting niche of Amish machine shops and machining monks, I took the bait.

Soon and with a strong dose of luck, I found myself speaking with Brother Isidore, head of CNC operations for the Carmelite Monastery of Meeteeste, Wyoming. I was surprised to receive a call back, to be honest. Just as, I soon learned, he was surprised to have been called in the first place.

By the time Brother Isidore and I talked he had already shared some incredible images and videos from the Carmelite monastery’s website of giant five-axis machine tools sculpting massive stone blocks into Gothic structures and inspired works of art. But after two minutes on the phone with Brother Isidore, it became clear that the CNC machining side of the story — the How of it all — was incomplete without the Why.

Hard Work is the Point

“I’m just curious, how did you find me?”

Brother Isidore sounded surprised to have received a call from a trade media editor, especially one who was blathering on in a voicemail about CNC machining and stone carvings and a potential article for Modern Machine Shop. I explained that I had found his phone number buried somewhere within the monastery’s website, on a page dedicated to the ongoing construction project. It simply felt like a good place to start, I said.

We scheduled the interview for a couple of weeks later. Unfortunately for me, it would have to take place over the phone as I would not be allowed to visit the complex. The Carmelite monastery is cloistered — secluded and specifically off limits to anyone except men seeking to devote themselves to a monastic life in pursuit of their faith. Not the news I was hoping for.

The Carmelite Monastery of Wyoming is situated on 2,500 acres in a nestled valley of the Rocky Mountains, now home to 26 monks. Since I wouldn’t be able to shoot my own photos and videos, Brother Isidore said, he would be willing to provide several high-resolution images and video clips of the CNC machining work and stone carvings destined for the monastery’s new Gothic church. And oh brother, did he deliver.

We set up a shared online folder where, soon enough, I found dozens of photos of the monastery construction project. Most were focused on CNC stone carving operations, and some were reminiscent of the many images I’ve shot at traditional machine shops save for the stone rather than metal parts.

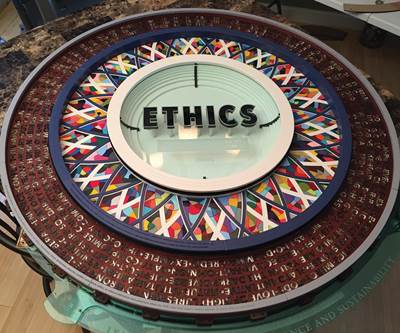

But the parts he presented were also art. Pure art. Functional art. Organic forms — animals, vines, angels and flowers — meticulously carved from limestone and granite that will last for centuries. It was art that, in another era and without CNC, would have taken decades or longer to produce.

And then, during our conversation, Brother Isidore shared how the monastery came to be, how they first adopted and learned to program and operate machine tools, and how they fit the work into their horarium, the monastic daily schedule that includes praying the Psalms at midnight.

And these Hows were fascinating, but the story was incomplete until he talked about Whys of the project: Building a traditional Gothic stone monastery from the ground up with little money and a just handful of workers. Adopting CNC machining with zero experience among anyone. Attempting a project that, given those constraints, could take decades or longer.

You do not have to be part of any organized religion to appreciate devotion. Nor beauty, nor compassion. Any emotionally functional human can recognize and appreciate these qualities. But when Brother Isidore said that the monks’ central apostolate — their chief calling as monks — is to pray for the world, I believed him.

“What we’re doing here — if something is really hard to do,” he said, “that’s worth something, isn’t it? Suffering is worth something. And we try to use all of that. It shows a lot more love than something that’s easy, right?”

And that was that. The project, the mission, was simply bigger than those tasked with seeing it through. The world is hurting right now, he said, and the world is starving for beauty.

And maybe that is reason enough.

Read Next

When a Part Becomes Art

Gears are gorgeous on their own, but watching the interaction within a gear set is especially intriguing. Read how this artist taught himself to make gears in order to power the drive of an art installment.

Read MoreThe Art of Maintaining Continuous Improvement

Production efficiencies, setup efficiencies, plant utilization record, safety records, on-time delivery performance — all of these metrics and more place Forest City Gear among the elite when it comes the use of ongoing improvement methodologies.

Read More