Inside a CNC-Machined Gothic Monastery in Wyoming

An inside look into the Carmelite Monks of Wyoming, who are combining centuries-old Gothic architectural principles with modern CNC machining to build a monastery in the mountains of Wyoming.

Share

The Carmelite monks of Wyoming — known formally as the Monks of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel — are a contemplative, cloistered community established in 2003 by two men in a remote Rocky Mountain territory in Meeteetse, Wyoming, about a two-hour drive west of the Bighorn National Forest. In 2010, after several monks had joined the two founders, the small group acquired a 2,500-acre mountain property and began the work of bringing life to a vision: Building a traditional, Gothic-style monastery from the ground up, constructing it chiefly from carved stone and wood. Fast forward to today, and the Carmelite Monastery includes housing, meeting rooms, a dining hall and a Porter’s Lodge that serves as the gateway to the complex. The main entry doors here are closed to the outside world, opened only to the knock of young men seeking a monastic life in pursuit of their faith.

The monastery today has 26 members, each of whom follows a structured daily schedule, known as the horarium, that includes chanting the Psalms at midnight and intervals of prayer balanced between periods of manual labor. Today, much of that manual labor is dedicated to the construction of the monastery’s crown jewel, a Gothic church that, when finished sometime around 2030, will contain more carved stone than the rest of the monastery combined.

Brother Isidore Mary joined the monastery in 2010, fresh out of high school. After working for a brief time at the coffee roasting business the monks had established to support their growing community, Brother Isidore was assigned to join – and eventually lead — the small crew of young men responsible for manufacturing and constructing the monastery structures. By then he was familiar with the nuanced approach to modern technology held by the Carmelite order — a respect for tradition combined with an openness to modern technologies that can support the monks’ mission, work and spiritual life. One of the tools that Brother Isidore began experimenting with was a Prussiani New Champion Plus 1300, a large-format gantry-style five-axis CNC machine tool designed to cut stone.

The monks’ dedication to building a Gothic-style monastery led to immediate challenges. Facing prohibitive costs for contracting traditional stonework and construction, the group set forth with fabricating the stone structures themselves. Their CNC machines, introduced to the monastery in 2013, today transform massive blocks of limestone and granite into both structural and decorative elements, the intricate designs and tool paths drawn and programmed in CAD/CAM software. Diamond cutting tools machine the stone blocks unattended through the night, milling and grinding the organic designs — angels, vines, flowers, animals — characteristic of medieval cathedrals.

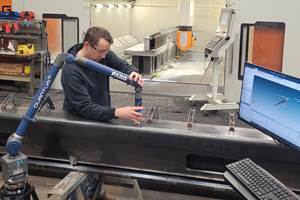

I talked to Brother Isidore about the Carmelite Monks’ journey from 2003 until today, about their use of CNC machining and how the work integrates with and deepens their spiritual lives. The following passages are direct quotes from that interview, edited for length and clarity. Each of the quotations also serves as a caption to (or at least an interpretation of) the photo that precedes it. All images were provided by Brother Isidore and the Monks of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel.

“By 2010, we had been given enough money to buy the mountain property that the monastery is situated on. It’s a 2,500-acre property, and we had just enough money to make a very low-ball offer. I think we offered maybe 40% of what it was listed on the market for because that was all we had. It took about a year, but eventually the seller, because he didn’t have anyone else interested, actually sold it to us — a huge miracle. With that hurdle crossed and now owning the property, we looked into, OK, now how do we build a monastery? What’s it going to cost? We got an architect involved. We had several high-level national contractors come in to provide quotes. And we quickly realized that we could never, ever afford to build something like this. Just the cost of the stonework alone was astronomical. It was something where we knew we could never raise that kind of money or earn it through our own work, our own industries. So the next logical question was, how do you carve stone? How can we do this ourselves? We can’t afford to pay somebody to do it, so we’ll learn how to work the stone ourselves.”

“I think there’s an idea that monks are kind of closed-minded in the sense of archaic, right? We think of monks as medieval ages, Dark Ages, somewhere in the past, and not the typical group of people to embrace technology. It’s a little different, I suppose, when you really get into the monastic culture. A lot of the culture of Western civilization was built out of monasticism, and many of the inventions and early scientists were actually monks. We found it very normal for monks to use the latest in modern technology to accomplish this, to kind of bring it all together. And so we immediately started looking into CNC machines. What kind of CNC machines can work with this kind of large, dimensional stonework?”

“Our starting blanks — the blocks coming in from the quarry — range anywhere from 15,000 to 30,000 pounds. We do all the processing, from that down to the finished piece, all in-house. We do have a water jet we use for other work, but for the thicknesses that we work with and the sheer size, I haven’t had a whole lot of success with it for stones of that scale. They’re almost too thick to cut cleanly with the water jet, and they are extremely three-dimensional pieces. But for anything — any straight profile — I can just cut that on the wire saw right out of the blank and we’re done. Some pieces we’ll rough out that way and then throw on another machine for further processing. Every piece is different.”

“It was a huge learning curve. None of the monks came with a background in manufacturing, a background in stone, more or less a background in anything useful for this. We got the first CNC machine in October 2013 after a benfactor gave us the money to buy it, and we still have that same machine. It’s still working very well for us. It’s a Prussiani — an Italian machine made specifically for stone. To give an idea of the work envelope, it's 3.8 meters in X, 3.5 meters in Y and 1.3 meters in Z — full five-axis plus a turret.”

“At the time, I was working at Mystic Monk Coffee, the industry that the monks started in 2007 to support ourselves. We’re in the middle of nowhere, Wyoming, and we needed some way to put food on the table, right? We can’t expect to just live off donations when we’re surrounded by poor ranchers. (Editor’s note: Donations are still integral to the building project.) And so we started an online business back then. I came into stone carving at ground zero, knowing nothing, and over a lot of trial and error — a very lot — I gradually picked it up. I guess I’ve been doing this now for about 10 years. I started as the operator/programmer and mechanic, everything involved with running that machine, and we just had the one machine doing everything.”

“Over the past 10 years, we’ve completed most of the monastery buildings. The last one, the crown jewel, is the church itself. There will be more stone in that than in all the other buildings combined. It has a concrete block masonry reinforced core because we’re near Yellowstone. We’re in a seismic zone; we have to build for earthquakes. But the dimensional stone on it — there’s stone inside, stone outside, fully clad. I think the thinnest points are maybe eight inches thick and it goes up from there. It’s just a lot of stone and extremely ornate stone.”

“We’re using a lot of granite on the exterior, just a more durable stone, but it hasn’t historically been used on this kind of building — something this ornate. And so it’s really an interesting challenge. Something even just in the past year that we’re definitely grappling with is how to work with a stone that’s a comparable hardness to carbide. For our tooling, everything’s diamond. Absolutely everything’s diamond because you can’t cut granite with anything else. And then just the struggles with tool life, because you’re wearing out these diamond bits extremely fast. Some of the roughing tools are designed to wear back three-quarters of an inch. And so for those, we currently have measuring probes in two of the machines. Basically, once every hour or so we do in-process measurements to update the tool length and keep going.”

“Everything is flooded by water coolant in all the cutting. That keeps the dust down. And then, if our housekeeping is good, that sludge never dries out; we get rid of it before it actually dries and turns into airborne dust. In terms of the debris, it’s all benign waste — it’s dirt, rocks, stone chips. So we can just use that in our own excavation construction — we actually use it as a construction material in some of the mortars, different things like that.”

“We’re working a lot more with the granite right now, and I think the first time we actually put a tool to it — it was a roughing wheel, I want to say it was like three-and-a-half-inch diameter — we immediately got a shower of sparks. With stone sparking, you’re like, is that supposed to be sparking? And we found out that we had an extra sixteenth of material on there, more than we were expecting on the blank. (With limestone) that didn’t used to be a problem. But with the harder stones, your tolerances are a lot tighter in terms of what the machine can handle and what the tool can handle.”

“For actual CAM programming we use a couple different programs. We use Pegasus, which is a stone-specific Italian program we’ve used for the past decade or so. It’s been really great to work with them because they’re small enough we could give them feedback, and they’ll use it; they’ll put it into their program. And then, more recently, we’ve also gotten into using Mastercam because has a lot of features and abilities that we’re finding very useful.”

“We’ve been doing lights-out machining since I started, for the past 10 years. That is just because it takes a long time to cut stone. It’s not fast and the pieces are huge. So right now, I think we’ve got all of our machines running — like at this actual moment they’re all running. One of them is running a piece that takes two weeks — just one op, two weeks — and that’s two weeks around the clock, 24/7.”

“The programming can be extremely labor-intensive. Most of our stuff is fairly complex. Even pieces we consider simple, there is just a lot going on. In the really complex stuff — we’re talking something sculptural — there’s a lot of undercut, very deep undercutting, a lot of very organic shapes. And it’s just time-consuming. We use five-axis regularly and freely, you know, full simultaneous five-axis, and it’s a mix of that and 3+2 machining. A lot of the challenges are with roughing out into pockets and getting enough material out in the roughing that we can then attack it efficiently in the finishings, and hitting the 500,000 angles, or just working with actually getting the finishing into all the different areas, the intricacies.”

“Stone is a hard thing to plunge into. It really doesn’t like it. So, working with the right drilling techniques before we then go in and rough out a pocket — maybe drill in an entry hole, things like that — these are all things we experiment with and use. The first challenge is, OK, how can we remove as much material in there as fast as possible? The most efficient way that we’re always looking to use first would be a saw blade. A lot of our machines, we can actually put a saw blade on the machine. And so the larger five-axis machines we have can handle a 40-inch saw blade. You cut off a wedge of material, and then it’s just gone. You don’t have to grind through that whole block. So that’s always first what we’re analyzing, just looking at the part: How can we attack this? How can we get that material off quickly and then go in with the rest of the roughing?”

“Our life is extremely structured. To give you an idea of a monastic horarium — basically, a horarium would be like the schedule of the day. So monks are up at midnight praying. A huge part of a monk’s life is to actually pray the Psalms from Sacred Scripture. So we’re up at midnight praying the Psalms, back to bed, up again at six in the morning, and then the rest of the day is punctuated by prayers, and then the work kind of in between that. And so it provides a certain rhythm to your life, a consistency. The inconsistent part is the work, because you never know what’s going to happen, what’s not going to work out for you that day. But it definitely — just kind of taking that rhythm, that steadiness to your work, taking that optimism that this is a lot bigger than just you, what’s going on, what we’re doing, what we’re accomplishing.”

“The work we do in the monastic life is a prayer. That’s the way we look at it. Our whole life is integral. I have found, just in talking to different people outside of the monastery, that it gives us kind of a unique concentration, in a way, on what we’re doing — problem-solving, figuring things out. It’s a kind of an optimism that, well, maybe this isn’t working, but something is going to work and we’re going to figure it out. Just keep plugging away, keep giving it our everything, and miracles happen.”

“We wanted to give our absolute best. We’re building this monastery for God. It’s not for me; it’s not for the other monks. In the end, we want to give Him the absolute best. The world is hurting right now. The world is also starving for beauty. We've lost a lot of that in the past 50 or 100 years, where there's no beauty in structures, no beauty in a lot of things. That is why these absolutely magnificent structures like the Notre-Dame in Paris are absolutely mind-blowing. And why did they build it? Because they had faith in something far bigger than themselves. They knew that this building wouldn’t be completed in their lifetime, wouldn’t be completed in their children’s lifetime. They knew they were giving their lives to something that was so far beyond them. We’re just bringing that mindset into this. It’s who we are. It’s part of our identity.”

Related Content

ESOP Solidifies Culture of Continuous Improvement

Astro Machine Works’ ESOP rewards all employees when the shop does well, inspiring many toward continuous improvement as Astro expands its capabilities.

Read MoreSelect Machining Technologies Highlights Multitasking Machines

IMTS 2024: Select Manufacturing Technologies is highlighting large-capacity multitasking machines from Solace, Geminis, Ibarmia and Momentum.

Read MoreThe Cut Scene: The Finer Details of Large-Format Machining

Small details and features can have an outsized impact on large parts, such as Barbco’s collapsible utility drill head.

Read MoreHow a Custom ERP System Drives Automation in Large-Format Machining

Part of Major Tool’s 52,000 square-foot building expansion includes the installation of this new Waldrich Coburg Taurus 30 vertical machining center.

Read MoreRead Next

Setting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More