Share

Continuous improvement is an act of continuous change. Blair-HSM South has learned this lesson firsthand, with the Wilmington, North Carolina, shop’s ambitious overhauls of its strategies for both people and machines paying dividends for productivity, retention and profits.

Jim Flock, general manager of Blair-HSM South, says the F-35 comes in multiple variants, each of which has slightly different specifications and uses different materials. Add to these left- and right-hand parts, and Blair-HSM South’s range of parts is much wider than it may seem on the surface.

Shop in Transition

Blair-HSM South was founded in the early 1990s as a satellite shop for an aerospace manufacturing shop on Long Island. Management intended for this shop to be a low-cost facility, and ran it that way. Jim Flock, the facility’s general manager, says the approach at the time was “just getting warm bodies to press buttons,” with work that required more skill being sent to the Long Island location. Retention was abysmal, with most people leaving for other jobs as soon as they had enough experience.

Flock was hired in 2015 to take over from the facility’s original manager, who was retiring. Upper management in New York was starting to change its outlook around this time and wanted to begin developing its satellite facility. Flock led the charge on this effort, lobbying for more training, better compensation and additional benefits. With increased employee satisfaction came improvements in retention, and the machinists of Blair-HSM South were better positioned to optimize their process.

This shift accelerated once the Magnaghi Group (MA Group), a company based just outside of Naples, Italy, purchased Blair-HSM. Blair-HSM had a long history of working in the defense markets, which MA Group wanted to begin serving. The shop has since made use of this push to improve inspection and quality standards, improve work conditions, emphasize repeatability and efficiency, and improve in the same areas as Flock and Blair-HSM’s management had targeted for improvement.

Today, Blair-HSM South employs 16 people: eight machinists, two deburring experts, four inspection personnel, one part-time trainee and Flock. With such a small staff, cross-training is the norm in the facility, which Flock says has helped with filling in when employees use their sick days and take vacations.

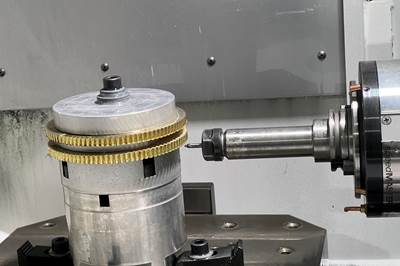

The scope of what these employees handle has also increased in recent years. Blair-HSM South has long used lathes, vertical mills and manual machines, but recent efforts have focused on its three Niigata horizontal machines: one HN63D with two pallets, an HN80D-II with eight pallets and another HN63D with 10 pallets. While the shop’s small lot sizes (20 parts might be a large lot for the shop) prevent robotization at this time, these pallets have given the shop the opportunity to perform some lights-out work. The machines’ controls have enabled an equally sizable shift for the shop: high-speed machining.

Flock estimated that filling an end mill with inserts may cost around $32 — already lower than a hog mill’s base cost of about $42, and certainly lower than the cost of the regrinding the hog mill would need to match the inserts’ productivity.

Whole-Hog Into High-Speed Milling

High-speed machining began replacing hog milling operations last year across eight different parts. Foremost among these was machining the forging of an F-35 torque arm, a common part for the shop. Hog milling took large cuts around the part but proved to be a slow solution, while high-speed machining enabled smaller, much faster waterfall cuts.

When Flock first joined Blair-HSM South, hog milling these torque arms was a 20-hour operation. Optimizations since that time brought hog milling cycle times down to about six hours. While an improvement, the shop still experienced backlogs during periods of high production demand.

Ultimately, Shop Foreman John Lent and Production Manager Josh Garrett began investigating high-feed machining techniques as an alternative. Once Lent selected appropriate tooling, Garrett performed time studies and found high-speed machining could cut cycle times to between 30 and 40 minutes.

For one version of the torque arm, adopting high-speed machining saved 824 hours a year. On another, the switch from an expensive hog mill — and the regrinding operations necessary to maintain it — to milling inserts saved $11,500 of tooling a year. For the whole part family, it saved around 101 working days.

While not every part from the original part family experienced as dramatic an improvement in cycle time and tooling cost, all the parts experienced some improvements. As a result, one of the shop’s 2023 goals is to expand the use of high-speed machining to other part families.

Manual Work, Lights-Out and the Necessity of VMCs

Blair-HSM South will not be able to substitute all its current milling operations for horizontal high-speed machining. For starters, some of the parts the shop works with are too heavy for the pallets. Others simply need tooling holes so machinists can clamp ODs and IDs on both sides of the part.

The shop’s vertical machining centers handle these operations, as well as several others. For example, while it uses an OKK HM-600 machine for holes, the shop’s machinists can use the rotary table on its Yama Seiki VP 2012 HD to machine flat surfaces on round parts, or simply to machine multiple sides of parts in a single clamping.

Because the parts at Blair-HSM South’s location are not heat-treated until they reach Long Island, tolerances are a little looser than they might otherwise need to be. “Loose” is only a relative term, however, with pivot points and hole diameters needing to meet ±0.001-inch tolerances.

The shop also takes care to maintain its manual machines. For the most part, these handle repair work, but Blair-HSM South also uses manual machines for odd operations that are awkward to load on a horizontal and need excellent ease of access. Flock says these operations could, for the most part, be completed on a CNC — but with the company’s small lot sizes, it is more efficient to conduct these operations on a manual machine.

These manual and vertical operations all take place during the day during a single, staffed shift. Once the last batch of parts for the day is ready for a clamp change from its first to second operation, the machinists fixture as many parts as they can to the tombstones in the Niigata machines, check that the tool carousels are correctly set up, and leave the machines to run overnight.

Between overnight work and the efficiency of high-speed machining, Flock says Blair-HSM South has saved so much cycle time that the shop has been looking to tackle additional work. As-is, the shop works 4×10 weeks, only calling in machinists for a half-day on Friday when necessary (and counting it as overtime). That said, management still works a five-day week, taking care of necessary projects as needed. In Flock’s case, this time also gives him a chance to indulge in running parts, rather than spend all his time managing.

No Fear in Cape Fear

But manage he does — and well. Enough so that Flock is also a central part of the Cape Fear Manufacturing Partnership, an organization composed of members from 52 manufacturing companies across three counties, from GE to a guitar manufacturer to a BBQ grill manufacturer to Blair-HSM South.

Like many local manufacturing boards, one of the Partnership’s primary objectives is to change the public narrative around manufacturing. Blair-HSM South’s own shift from what Flock calls the dirty conditions of “your grandfather’s machine shop” to a more high-tech operation helps the cause, as does demonstrating the ±0.001-inch tolerances the shop produces.

A large part of Flock’s advocacy efforts involves reaching out to schools and working with them to create training programs. With Wilmington largely serving as a vacation community, Flock says the two most common career paths in the area are hospitality and elder care, neither of which have great paths for promotions and raises. Manufacturing, on the other hand, can offer a more promising proposition — especially with a nearby manufacturing plant for GE.

Even the smallest Niigata horizontal machine saves time when high-speed machining compared to older machining methods. Flock hopes to add machine monitoring to Blair-HSM South’s machines to further improve utilization, a change already making differences at the company’s Long Island facility.

Even for smaller shops like Blair-HSM South, manufacturing can appeal as a more promising career path. Just a few weeks before my April 2023 visit, Flock was on his way back from a meeting when he stopped at a gas station. The clerk on duty noticed Flock’s suit and assumed he was a businessman; upon hearing that Flock worked in manufacturing, the young man inquired further and asked to interview for a position.

Now, this chance encounter has led to a new part-time employee. Flock says they are still rotating the young man through positions, assigning him to the inspection and metrology department for an hour each day before sending him to shadow machinists on the shop floor. It’s a far cry from the shop’s usual training methods, in which new hires come on full-time and work supervised on less-complicated machines, moving to more complex machines and work as their skills improve, but it reflects a willingness to expand the shop’s talent pool.

Ironically, Blair-HSM South does not have a formalized apprenticeship program. Flock has still leveraged the knowledge he has gained through the Cape Fear Manufacturing Partnership to attract workers, however, using work-experience grants to hire people for a two-month trial to see if manufacturing is the right fit. If it is, Flock has been able to use on-the-job-training grants that pay for 80% of the new hire’s first-year salary—a modern solution to a modern problem, as the shop continues to transition from a shop of yesteryear to a shop of tomorrow.

Related Content

CNC Machine Shop Honored for Automation, Machine Monitoring

From cobots to machine monitoring, this Top Shop honoree shows that machining technology is about more than the machine tool.

Read MoreHigh RPM Spindles: 5 Advantages for 5-axis CNC Machines

Explore five crucial ways equipping 5-axis CNC machines with Air Turbine Spindles® can achieve the speeds necessary to overcome manufacturing challenges.

Read MoreHow to Mitigate Chatter to Boost Machining Rates

There are usually better solutions to chatter than just reducing the feed rate. Through vibration analysis, the chatter problem can be solved, enabling much higher metal removal rates, better quality and longer tool life.

Read MoreInside a CNC-Machined Gothic Monastery in Wyoming

An inside look into the Carmelite Monks of Wyoming, who are combining centuries-old Gothic architectural principles with modern CNC machining to build a monastery in the mountains of Wyoming.

Read MoreRead Next

5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreFour-Axis Horizontal Machining Doubles Shop’s Productivity

Horizontal four-axis machining enabled McKenzie CNC to cut operations and cycle times for its high-mix, high-repeat work — more than doubling its throughput.

Read MoreFive-Axis Changes Weldments Into Monolithic One-Piece Parts

Moving from welding to five-axis machining enabled Barbco to redesign its weldments as monolithic one-piece parts with improved strength and repeatability.

Read More