Share

Examples of different parts and materials that have been superfinished. All photos courtesy of Nagel Precision Inc.

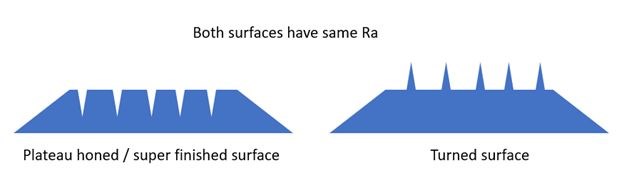

There is a constant pressure on manufacturers to both enhance the efficiency of manufacturing and enhance the performance of manufactured products, often by taking the weight out of components. For automotive manufacturers, this is coupled with pressure to reduce emissions. According to Sanjai Keshavan, manager of the ECO Hone and Microfinishing Systems Division of Nagel Precision Inc., all these pressures helped lead to the development of superfinishing — a finishing process first applied to production around the 1930s that is designed to enhance a component’s surface finish while also improving its micro-contour accuracy through improved roundness, straightness, cylindricity and more.

Despite its usefulness for automotive parts, the application potential for superfinishing is wide-reaching. From job shops to large original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), superfinishing has found roles in small medical parts such as hip and spine implants and aerospace parts such as turbine and landing gear components. According to Keshavan, superfinishing can conceivably be used in any OD application that requires the precise removal of small amounts of stock on the order of 0.002-0.005 mm from the diameter. While steel is the most common material to superfinish, he says, the process can also be applied to exotic alloys, titanium, aluminum and even glass and ceramic.

One of superfinishing’s main benefits is that it is a cold material process, which means it eliminates the thermally damaged layer that is left by previous operations such as grinding. This has a key impact on extending component life. For example, Keshavan says that if the bearing surfaces of an engine crankshaft or camshaft were not superfinished, component stress and wear could lead the engine to break down every 20,000-30,000 miles instead of the 200,000-300,000 miles as is common for today’s engines.

So, how does superfinishing remove stock without the heat that is so typical of abrasive machining? The answer has to do with depths of cut. “When you turn or grind a part, the depths of cut could range from 50-100 microns or higher,” Keshavan says. “Removing that amount of material in a short amount of time requires lot of energy, and the part heats up. Superfinishing removes 1-2 microns of stock on radius and requires less energy.”

Choosing a Finishing Process

While manufacturers often use various finishing process terms interchangeably, Keshavan says each process has a subtle nuance that may make it better suited for a particular application. Here are some common finishing processes to compare:

-

Lapping – Finishing of flat faces with loose abrasives. Here, the improvement of surface finish is accompanied by improvement in flatness of the part.

Flat lapping.

-

Honing – Finishing of internal diameters with fixed abrasives. It is considered a cold process, as heat is not generated during this operation. Improvement of surface finish is accompanied by improvement of micro-contour accuracy.

Honing.

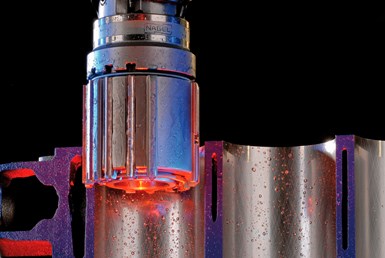

- Microfinishing/ superfinishing – Finishing of external diameters and faces with fixed abrasives. It is considered a cold process, and it also improves the micro-contour accuracy.

- Polishing – Finishing of outside features with loose abrasives. Both brushing and vibratory finishing are examples of a polishing process. This is not considered a cold process, and significant heat can be generated during the finishing operation. Improvement of surface finish is accompanied by loss of micro-contour accuracy.

Superfinishing with tape.

Superfinishing with stone.

Both superfinishing and polishing are used to create a fine surface on outside diameters. Polishing is a more flexible process because a brush, a lapping compound or a vibratory process like tumbling can all be used. Tumbling makes it possible to polish many parts at once. In contrast, superfinishing uses a fixed abrasive to impart the finish, and only one part is finished at a time. Keshavan says superfinishing has advanced beyond hard tooling. To add more flexibility to the superfinishing process, his own company, Nagel, has developed what it calls “D-flex” band technology that acts like a fixed abrasive but can flex to compensate for as much as a 15 mm change in diameter.

Determining which finishing process to use depends on the end use of the part. Keshavan says, “Polishing is best suited for applications in which part geometry is not critical and aesthetics are the main concern; superfinishing is best suited for mission-critical parts.”

Related Content

Arch Cutting Tools Acquires Custom Carbide Cutter Inc.

The acquisition adds Custom Carbide Cutter’s experience with specialty carbide micro tools and high-performance burrs to Arch Cutting Tool’s portfolio.

Read MoreMarposs Celebrates its Past, Eyes Future Opportunities

During its open house in Auburn Hills, Michigan, Marposs presentations focused on future opportunities across growing industries such as EV and semiconductors.

Read MoreDN Solutions Responds to Labor Shortages, Reshoring, the Automotive Industry and More

At its first in-person DIMF since 2019, DN Solutions showcased a range of new technologies, from automation to machine tools to software. President WJ Kim explains how these products are responses to changes within the company and the manufacturing industry as a whole.

Read MoreFaster Programming and Training Helps Automotive Shop Thrive

Features that save on training, programming and cycle times have enabled Speedway Motors to rapidly grow and mature its manufacturing arm.

Read MoreRead Next

Answering 5 Honing FAQs

Honing is typically performed to bring bores to a precise size or achieve a specific surface finish. Here, a leading honing equipment manufacturer answers a few commonly asked questions about this process.

Read MoreClamp Bore Face Grinding and Honing Creates Higher-Quality Gear

Nagel's ECO 40 hone and SPV clamp bore face grinder helped Global Gear and Machining to produce gears with stringent bore-to-face perpendicularity tolerance.

Read MoreFor Superfinishing Excellence, Start With The Right Finish

The key to excellence in superfinishing operations is the incoming grinding finish on the workpieces. With the right start, superfinishing is a very effective and economical process for achieving mirror-like finishes.

Read More