For Superfinishing Excellence, Start With The Right Finish

The key to excellence in superfinishing operations is the incoming grinding finish on the workpieces. With the right start, superfinishing is a very effective and economical process for achieving mirror-like finishes.

Share

Takumi USA

Featured Content

View More

Hwacheon Machinery America, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Most manufacturers see grinding and superfinishing as separate operations. Unfortunately, the most meticulous superfinishing setup, using the best equipment and the latest abrasives technology, cannot correct all of the problems (many of them subtle) which can be introduced in the previous manufacturing step. Conversely, achieving desired geometry and finish at the highest rate of productivity with superfinishing can only be accomplished by taking the incoming operation into consideration.

One of the conditions for producing uniformly good parts from a superfinisher is a consistent level of finish from the grinding operation. The rough finish for the incoming part should be approximately 10 or 15 Ra (microinches). This level of finish makes it possible for the superfinishing stone to aggressively cut the surface profile and bring the finish down to 5, 2,1Ra, or whatever the specification requires. The more consistent the incoming finish, the more consistent the output will be from the superfinishing operation.

Here are some grinding occurrences that will thwart superfinishing consistency:

Too Smooth A Finish

Ironically, one of the most common of all grinding problems in relation to superfinishing is too smooth a finish. It is still not widely understood that too smooth a finish from the grinding operation is a negative factor. When the superfinishing stone rides on too smooth a surface, it begins to glaze, causing it to ride on a film of oil and remove very little material from the part. A coarser finish tends to keep the stone open, so it can cut more freely.

Engineers and grinding machinery operators typically take a great deal of pride in their work. Wanting to do their best, they try to get the finish as low as possible. When this happens, the hone stone is unable to bear into the part and remove the amount of stock required to reach the specified result.

Another reason why incoming finish is often reduced from optimum to a low limit is a byproduct of wanting to increase grinding throughput. Extending dress cycles to a bare minimum maximizes throughput but it also results in a dull wheel which does not cut freely. When the wheel is dull, it produces a smoother finish and increases the likelihood of thermal damage, lobing and chatter.

The grinding operations need both upper and lower limits on the finish specification. Avoiding overfinishing will result in a better superfinished part and improved grinding productivity. Here's an example.

The throughfeed superfinishing operation for an automotive engine component was set up based on an incoming part finish of 6 to 8 Ra, removing 30 to 50 millionths of stock to produce a 1 Ra finish. The finish from the grinding operation was allowed to deteriorate to 3 or 4 Ra. Because the stones could no longer efficiently penetrate the part, superfinishing stock removal fell to about 10 millionths—insufficient to clean up the part. Although Ra was good, many of the parts were visually unappealing and rejected. When the grinding operation was directed to dress more frequently and grind more aggressively (to 6-8 Ra), the cosmetic issues were eliminated.

Thermal Damage

Trying to do too much finish work in the grinding operation can generate excess heat and cause thermal damage to the subsurface of the part. If the part is burned in grinding, it may still be possible to reach the desired level of superfinish but visual imperfections and metallurgical damage will likely necessitate scrapping the part. Superfinishing is not a fix for burned parts.

Burnishing

A problem frequently associated with thermal damage is burnishing. When the wheel is not cutting freely because it is dull, it generates excessive heat. Instead of removing metal, it pushes it around on the surface of the part, smearing it into the microscopic valleys. This may result in a smooth surface, but one that is not acceptably prepared for the superfinishing process. It is not as stable under load. Because this type of burnishing leaves softer metal on the surface of the part, it may become less wear resistant. Burnishing can create a situation in which the part looks good and meets specifications, yet is in fact an inferior part.

High Amplitude Lobing

A certain amount of lobing is associated with all internal and external diameter grinding operations. Lobing is generally caused by deflections in the system between the wheel, the work and the tooling when grinding forces are applied. As a result of these fluctuating forces, no workpiece is ever perfectly round. Instead, the workpiece will have a number of rounded projections call lobes.

When a stone can bridge two or more lobes at a time, it can then work to reduce their amplitude. See Figure 1, at right. Superfinishing can remove a certain amount of lobing—perhaps as much as 50 percent depending on amplitude, frequency and the application. Figures 2 and 3 show the relationship between incoming workpiece lobing and roundness improvement in superfinishing.

In Figure 2, a workpiece with an incoming surface finish of 10 Ra and lobing depth of 50µ (microinches) enters superfinishing. The superfinishing removes 60µ of stock (below the depth of the original lobes). The result is a workpiece with a 3 Ra surface finish and a 45µ of roundness improvement. The remaining 5µ lobes were left by the superfinisher itself.

In Figure 3, a workpiece with an incoming surface of 10 Ra and lobing depth of 75µ enters superfinishing. The superfinisher removes 60µ of stock (above the depth of the original lobes). In this example, superfinishing only removes the tops of the lobes and gives them a shining mirror-like 3 Ra finish. However, the 15µ valleys are untouched and continue to have a relatively dull 10 Ra finish. This roundness improvement may, or may not, be acceptable depending on the specification. The workpiece now has chatter marks—zebra like lines of contrasting surface finish causing the workpiece to be rejected for cosmetic reasons. The problem is not the superfinishing operation but excessive lobing of the workpiece.

High Frequency Chatter

Excessive lobing is not the only reason for chatter. It may also appear on incoming parts. A series of lines, generally a result of induced vibration caused by improper setup, worn equipment or poor wheel performance, is termed chatter. Some of the conditions that create chatter may also cause thermal damage to the part.

Chatter is a high frequency surface aberration superimposed on top of the lobing. It is like ripples on ocean waves. Superfinishing is far more effective in correcting chatter than lobing. Reducing chatter is important because it allows assembled components to operate quietly and with less vibration. It is a major factor in eliminating premature failure.

Ironically, superfinishing can sometimes make excessive chatter generated in the grinding operation look worse. When insufficient stock is removed by the super-finisher, the problem of chatter is actually highlighted. Superfinishing polishes the peaks of the chatter but the valleys remain dull in contrast. Previously invisible to the naked eye, chatter now becomes clearly visible and disturbing. Although it becomes obvious in superfinishing, chatter is a problem that is passed on from grinding.

Highlighted chatter due to insufficient stock removal in superfinishing takes us back full circle to the problem of too smooth an incoming finish. Of course, the superfinishing operation could use a softer stone which breaks down readily and cuts more aggressively. Another way to improve the efficiency of chatter removal is by selecting a stone geometry which presents more surface area to the part. The degree to which stone geometry may be altered depends on part geometry and the superfinishing equipment's capacity.

But changing the stone to compensate for grinding-related problems means less efficient superfinishing. Softer stones also wear out more often. The best solution is maintenance of quality output from the grinding operation.

What To Do?

Ideally, grinding and superfinishing operations should be synchronized to achieve the common goal of producing consistently good parts at the end of their interrelated processes. The grinder needs to take the workpiece to size within a prescribed semi-rough finish range and then leave it alone. There is a relatively narrow window in which to operate. Below 10m of surface finish, problems can appear in superfinishing; below 6m, they are almost certain. (Problems attributable to incoming grinding finishes are not the only ones superfinishing can face. Table I (below) presents some other common problems and suggests the appropriate correction.)

|

Table I

Common Superfinishing Problems And how To Correct Them |

|||

| Condition | Increase | Decrease | Other |

| Excessive stone wear |

spindle RPM |

stone/wheel pressure; reciprocation/ oscillation |

use harder abrasive product |

| Insufficient stock removal |

abrasive pressure reciprocation/ oscillation rate |

spindle RPM |

use softer abrasive product; use coarser grit abrasive product |

| Rough finish |

spindle RPM |

stone/wheel pressure; reciprocation/ oscillation rate |

use finer and/or harder abrasive product |

| Undesirable smooth finish |

reciprocation/ oscillation rate; abrasive pressure |

spindle RPM |

use coarser and/or softer abrasive product |

| Excessive heat generated |

coolant flow rate |

stone/wheel pressure |

use softer abrasive product |

| Out-of-round parts |

reciprocation/ oscillation rate |

stone/wheel pressure; spindle RPM |

use softer abrasive product |

| Glazing of abrasive surface |

reciprocation/ oscillation rate; abrasive pressure |

spindle RPM |

use finer and/or softer abrasive product |

| Loading of abrasive surface |

reciprocation/ oscillation rate |

spindle RPM |

use finer and/or softer abrasive product |

To contribute to much more effective superfinishing, the upstream grinder should use free cutting wheels and process parameters that properly prepare the part for superfinishing, while avoiding additional problems like thermal damage, chatter, lobing or burnishing. "We can always catch it later" should not be part of the grinder's thinking.

The grinding operation is the last chance to catch problems that could significantly impact manufacturing yields, even though the rejection may occur downstream and appear to be somebody else's problem. When yields from superfinishing are high and within spec, the grinder deserves much of the credit.

About the author. Jeff Schwarz is general manager of Darmann Abrasive Products, Clinton, Massachusetts.

Related Content

Lean Approach to Automated Machine Tending Delivers Quicker Paths to Success

Almost any shop can automate at least some of its production, even in low-volume, high-mix applications. The key to getting started is finding the simplest solutions that fit your requirements. It helps to work with an automation partner that understands your needs.

Read More5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreVolumetric Accuracy Is Key to Machining James Webb Telescope

To meet the extreme tolerance of the telescope’s beryllium mirrors, the manufacturer had to rely on stable horizontal machining centers with a high degree of consistency volumetric accuracy.

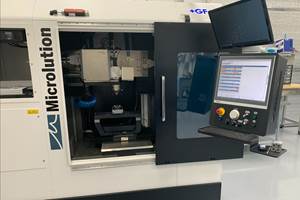

Read MoreWhere Micro-Laser Machining Is the Focus

A company that was once a consulting firm has become a successful micro-laser machine shop producing complex parts and features that most traditional CNC shops cannot machine.

Read More

.png;maxWidth=150)

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)