Too Small To Touch

Hummingbird takes on machining work that is too small for most shops to handle. In fact, Hummingbird tries not to handle it either. To accurately machine the tiniest parts, this shop relies on processes that are as hands-off as possible.

Share

“Micromachining” is the realm in which machining skill has a different meaning. Skills based on human hands and human senses can’t assist the process the way they do in “macro” realm.

For example, even in a highly automated machining process, manual skills are often very valuable. A skilled machinist can detect a problem simply by hearing the change in the sound of the cut. That machinist might also be able to finesse a setup to machine an accurate part despite some temporary deviation in the positioning of the tool, machine or workpiece. Many shops don’t even recognize the extent to which they rely on this level of oversight and intervention.

But micromachining can’t benefit from that kind of human element. The scale is too small. No change in the sound of the cut is likely to be heard, and any deviation in the dimensions of the setup is probably too fine for any human tweak to be able to compensate for it effectively. Indeed, as demonstrated by the array of microscopes throughout the shop floor at Hummingbird Scientific, it can take sophisticated equipment just to determine that a particular micromachined feature has even been produced at all.

Hummingbird specializes in machining tiny parts through milling, turning and EDM. The company got its start making components for powerful microscopes, but the Lacey, Washington firm recently spun off a second business—Hummingbird Precision Machine—that focuses on contract machining of tiny parts. The promise of this venture even led to an unusual relationship with a machine tool supplier (more on that below).

Norman Salmon is president of the Hummingbird companies. He says “machining skill” in the micromachining realm is something different. It consists of engineering a process that anticipates and eliminates sources of variation before they occur. There are many aspects to this, he says. Planning is a big part of it. So are precisely repeatable machines, fixturing and tooling. Though Hummingbird has some unusual equipment, Mr. Salmon says there is no technology sufficient to perform this work that isn’t commercially available. In some cases, in fact, the technology has been available for a decade or more.

Precisely Micro

Hummingbird literally does micromachining. That term—“micromachining”—is commonly used in an imprecise way. It often refers simply to work that is challengingly small. But machining at this company involves feature dimensions that

actually are measured in microns.

The original Hummingbird Scientific was founded 4 years ago to produce specimen holders for electron microscopes—powerful microscopes able to “see inside” materials at atomic resolution. Each specimen holder the company makes is customized for the application. One holder might have tiny actuators to rotate the sample under

the microscope. Another might include the equivalent of a tiny furnace to heat the sample to more than 1,000°C. Particular applications also tend to demand special materials for the holder. To deal with all of these needs, the Hummingbird staff includes Ph.D.-level specialists in physics and materials science in addition to the

engineering and micromanufacturing experts. The machine shop that supports all of this work is simply an extension of the company’s overall service. The shop isn’t consumed by this work, so Mr. Salmon saw an opportunity in the open capacity. Could he find outside demand for his shop’s ability to machine parts at micron scales?

Yes. However, Hummingbird may now be helping to create that very demand. Rather than full-scale production parts, the contract micromachining work the shop has won so far has consisted of process development, prototyping and first-article runoffs aimed at determining how effectively various newly designed components could be made. Most of these studies have related to potential new products that the customers might never have even considered before Hummingbird offered a practical way to produce some small component that is critical to the design.

Parts And Partnership

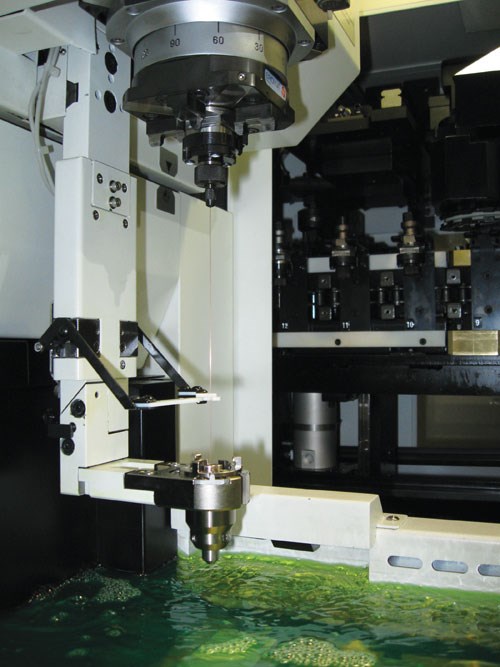

Makino was attracted to this exploration of what is possible in micromachining. Hummingbird’s three newest machines come from this machine tool builder, but its relationship with the company now extends beyond having machines on the floor. A joint venture between the companies also includes visiting staff on-site. Makino micromachining R&D team leader John Bradford now works at Hummingbird. He serves the Washington shop and its customers, and along the way, he also increases Makino’s knowledge of micromachining by reporting to the home organization (partly via an internal blog) about the lessons his current work is teaching him.

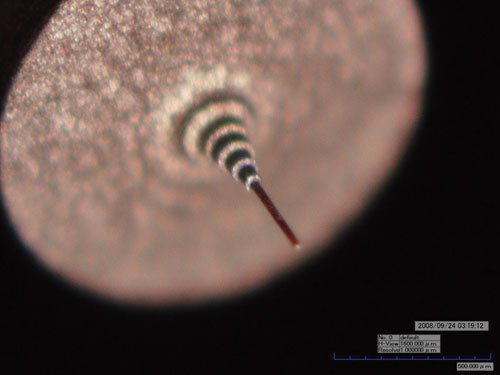

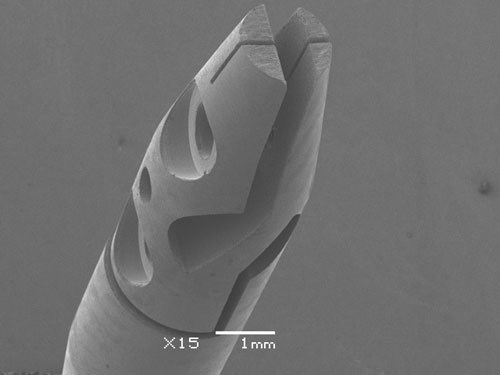

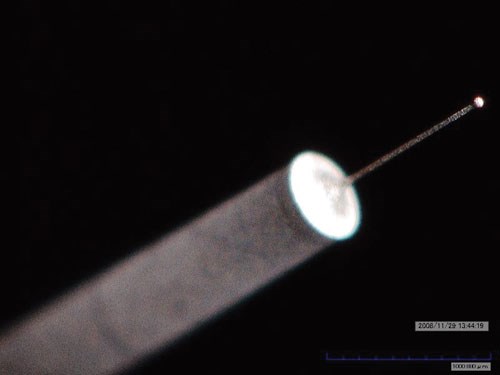

Photos at right illustrate the kinds of features and contract parts the shop has machined. The cylinder-shaped stairstep part measures only 14 microns at its smallest diameter. The part which resembles a coordinate measurement probe is exactly that. This tiny probe was made for metrology specialist IBS Precision of the Netherlands. The slender stylus is 1.000 mm and 70 microns in diameter.

Video footage shot through a microscope shows features of other micromachined parts, including channels that meet at a 50- by 50-micron passage and a 3-mm-diameter cylindrical part with a hex-shaped cavity. (See “Editor Picks” at far right.)

Micro EDM

The stairstep part and the probe were machined through EDM. Hummingbird’s EDM capability includes two machines not available anywhere else in North America, not even at Makino’s own U.S. facilities.

One is an EDFH1 fine-hole EDM capable of machining holes as small as 10 microns in diameter using a 6-micron-diameter electrode. The machine’s tiny electrodes are produced through electrical discharge dressing.

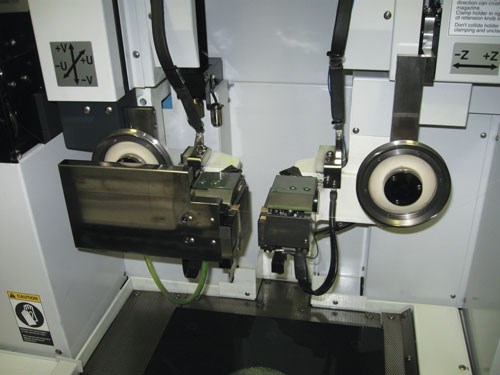

The other is a UPJ-2 wire EDM capable of automatically threading 20-micron-diameter wire through a 40-micron-diameter start hole.

Makino’s Mr. Bradford says the reliable threading on the latter machine is one of the keys to successful micromachining. The shop’s wire EDM can’t be a source of variation, either—meaning the wire threading has to work just as well for the finest wire as it does for heavier wire. On the UPJ-2 machine, the most significant design feature that makes the fine wire reliable is obvious to anyone familiar with wire EDM. That is, the wire is not vertical on this machine, but horizontal.

The horizontal arrangement protects the fine wire, says Mr. Bradford. One reason it does this is because the slug falls easily out of the way. A less obvious benefit relates to the wire tension, which is unaffected by gravity in this arrangement. Gravity instead pulls on a system of weights that maintain a constant tension.

The system for threading this wire involves opposing slender tubes and negative air pressure. Suction pulls the wire from one tube into another. (Video under "Editor Picks" shows this as well.)

One final advantage of the horizontal arrangement is that the rotary axis does not have to be submerged. This axis instead locates above the workzone. The work suspends from it.

Hummingbird clamps the work here using the Erowa “Fine Tooling System,” a locking chuck-and-pallet system that locates with 2-micron repeatability. The system allows the shop to set up work quickly and accurately not only on the EDM machines, but also on the shop’s machining centers, where the same system is also used.

Micro Milling

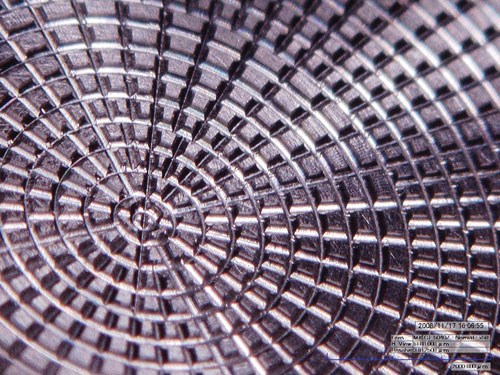

The EDM machines may be distinctive. By contrast, Mr. Salmon says micron-scale milling can be done on high-precision machining center designs that are widely accessible. The photo of a milled part shows an example. The part, a microfluidic component, features channels 200 microns wide. It was machined using a tiny milling cutter from Union Tool. The best machine tools developed for hard milling of conventional-size parts are potentially stable enough for this sort of work, Mr. Salmon says.

In fact, to give an example of just how long this technology has been available, he cites the shop’s Roku Roku machining center—a machine more than 10 years old. At 30,000 rpm, this machine develops dynamic runout error as

high as 5 microns. Assuming runout should be no more than 10 percent of tool diameter, this limits the machine to tools no smaller than 50 microns—easily sufficient for many micromachining jobs. The shop’s newer machining center is a Makino V22 capable of 40,000 rpm. This machine’s tighter runout has allowed the shop to mill parts using tools as small as 10 microns in diameter.

The process on both machining centers is significant for what it does not involve. While tool length on the V22 is measured as part of the process (see photos), no consideration on either machine is given to measuring tool diameter offsets or runout error prior to machining.

To do so would be to accept a source of variability, Mr. Salmon says. The better course for micromachining is to anticipate the variability and avoid it. Therefore, Hummingbird’s approach is to control runout to such an extent that it doesn’t have to be measured as part of the process.

Getting to this level of consistency means knowing the machine performance well enough to be able to predict the machine’s contribution to runout, however slight that is. Achieving this consistency also involves finding and sticking to tooling that is manufactured to sufficient quality that runout is never in question. This is particularly true for toolholders. The shop uses shrink fit and collet-type holders from two suppliers: Big Daishowa (Big Kaiser) and Yukiwa Seiko.

Perhaps ironically, Hummingbird’s president says he actually wishes the shop had a larger machining center. The V22 has a work envelope of about 1 cubic foot. The model V33 is the next larger machine in this family. He says this machine would offer no downside in terms of micromachining performance. However, such a machine would increase the shop’s capacity to take on larger parts. As the company gets into a greater variety of machining work and discovers customers who need both micromachined parts and related “macro” machined parts at the same time, he sees how useful it could be to occasionally complement the fine work with some standard-sized machining, too.

Related Content

Tsugami Lathe, Vertical Machining Center Boost Machining Efficiency

IMTS 2024: Tsugami America showcases a multifunction sliding headstock lathe with a B-axis tool spindle, as well as a universal vertical machining center for rapid facing, drilling and tapping.

Read MoreMitsui Seiki's Compact VMC Offers High-Precision Milling

The VL30 series is designed to machines high-precision mold inserts for medical, packaging, industrial and aerospace applications.

Read More5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreFryer Milling Machine Provides Fast Setup, Simple Programming

The MB-R toolroom bed mill is reportedly capable of single- or multi-part production with a 0.0002" accuracy.

Read MoreRead Next

Registration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)