Share

A machine tool is just that: a tool.

That’s one takeaway from a recent visit to Kustom Machining & Manufacturing, a 14-employee, 26,000-square-foot contract manufacturer in Jackson, Tennessee. “Many of our customers have the same equipment that we have,” says Matt Sellers, general manager, so the primary differentiator is how the machines are used. Customers (and competitors) might have the same capabilities, but, as he puts it, “they don’t have the same employees.”

Kustom Machining does not hire people to push buttons, he explains. Rather, the shop owes its profitability to what happens in the brief periods when machines are not running. The greater the staff’s skill at switching from one setup to another, the better they can help customers, including local railway industry manufacturers and food producer Kellogg’s, with small-batch parts that are too burdensome to machine in-house.

General manager Matt Sellers (left) started out sweeping floors and helping around the shop after his father, company president Larry Sellers (right), purchased Kustom Machining & Manufacturing nearly 30 years ago. Photo courtesy of Kustom Machining & Manufacturing.

However, Sellers’ praise for the rest of the shopfloor team understates an important contribution from management: setting this course in the first place, then aligning tools and talent accordingly. He recalls that Kustom was “not in a good place” when his father, Larry Sellers, purchased the business in 1993. Now, he confidently refers to the company as “one of the top machine shops in West Tennessee.” Specific elements of this shop’s approach to small-batch production include:

Lathe Tools Are Live

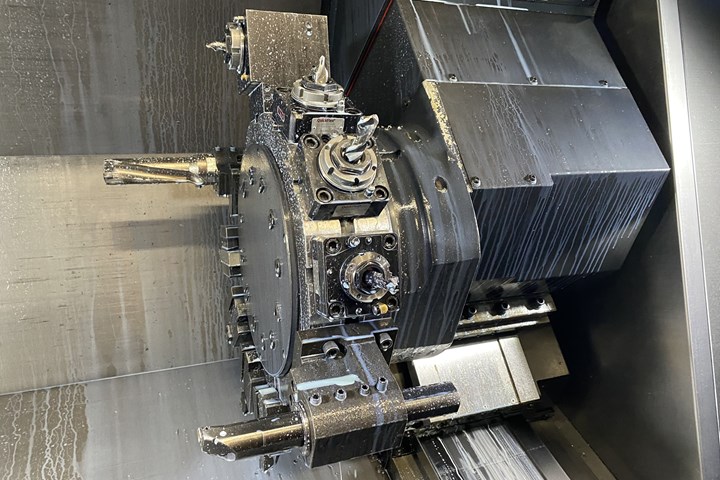

Tool turrets like this one approach the work along the machine’s Y axis for milling, boring and other operations.

High-caliber machine tools cannot take the place of high-caliber talent, but they can help make the most of that talent. Sellers says Kustom’s technology came to a significant turning point (so to speak) in 2012 with the purchase of the company’s first lathe with Y-axis milling capability. Capability to both mill and turn without an additional setup drove immediate time savings that compounded as the staff gained experience and the shop purchased more machines. Not coincidentally, the mid-2010s were also a period of steep sales growth, culminating in the shop’s best year in 2018 and steady profits since then.

That first live-tool lathe, a Mori Seiki NLX2500Y, is still on the floor. In the hands of the most experienced personnel, swapping out even the most demanding setups takes no more than two hours (less for repeat work with an established part program), Sellers says. It is one of three turn-mills at Kustom, two of which are Doosan Pumas that replaced older machine tools in 2018 and 2020, respectively. Generally, the shop aims to add or replace at least one new machine tool per year. Beyond raw machining capability, this is because newer options can speed job changeovers even for less experienced personnel.

When MMS visited Kustom, the shop’s newest machine purchase was not a VMC or a live-tool lathe. This saw is located in an adjacent building from those machines, along with welding and other structural fabricating equipment that complement metal-cutting.

Machines Do the Grunt Work

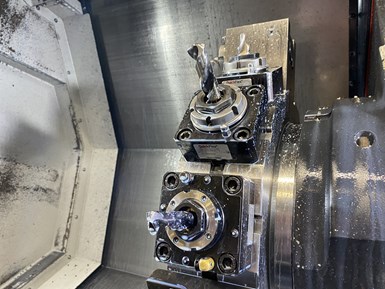

Automated toolsetting (above) and standardizing on certain cutters in certain stations in Y-axis tool turrets (below) are among the lathe features contributing to reduced setup times at Kustom Machining & Manufacturing

All three of the shop’s live-tool lathes feature programmable tailstocks. However, this was not the case for the machines that the two Doosans replaced. With this older equipment, the tailstock had to be manually and repeatedly maneuvered and locked into position. In fact, it became relatively common practice to save time by wrestling the tailstock just enough far enough to pull the part from the “wrong” end of the machine, near where the barstock loads. Now, “We just program it to automatically move in and out of position,” Sellers says. This is an example of a recurring theme in the shop: Rely on machines to do difficult or repetitive work rather than people.

As a general rule, tools stay in their turret stations for as long as possible.

When machines can’t do the work, the system does. For example, the shop has standardized on certain tools that work for multiple jobs. Copies of these tools can be found in the turret of every lathe, and the goal is to keep those tools in their stations for as long as possible. “If it hasn’t moved, it doesn’t need to be touched off again,” Sellers explains — that is, there is no need to jog the turret down and touch tool to workpiece to establish coordinates for a new tool.

That said, swaps are inevitable, and tools wear. This is why Sellers plans to purchase every new lathe with an integrated toolsetter, which, on the shop’s latest Doosan machines, includes CNC software and an arm that folds out to present a Renishaw probe to the tool turret. Automating touch-off and subsequent offset calculation not only saves time, but also prevents data-entry errors.

Milling Matters

The shop’s regular technology upgrades and focus on setup reduction also extend to dedicated milling equipment. For example, the newest Haas VF3 replaced an older version of the same machine just last year. Like the latest lathes, it features on-machine probing. However, this probe can be used not only for tools, but also for workpiece features, particularly close-tolerance bore diameters. “Without ever taking the part out of the machine, we can measure it, adjust our offsets, and re-run that part of the program.” Sellers says. “We can also check hole locations — say, center distances and outside diameters for a series of drilled and tapped holes — or X and Y locations on a rectangular part.”

Following plasma cutting, stress relief and Blanchard grinding on both sides, this part was set up on Kustom’s Haas VF-5 VMC for drilling and reaming nearly 600, 0.505-inch-diameter holes. The shop often schedules the last plate in an order for the end of the day, allowing the 2-hour drilling cycle to finish unattended and leaving the part ready for reaming the next morning. From there, a CNC lathe turns the OD.

Four Beats Three

As for setup reduction, rotary fourth-axis attachments enable the VMCs to act almost like lathes, with cylindrical parts in chucks revolving beneath the spindle to expose new geometry for milling. The fourth axis is particularly useful for cutting keyways into shafts, which the shop prefers to cut to length prior to this machining. “If you did it on the lathe, you’d have to saw them longer to have excess material to chuck on,” Sellers explains. “You can’t get that turret with the end mill all the way up to the chuck — you’ll hit the jaw.”

Due to overseas lead time for castings, a customer asked that this part be machined from barstock. Although bar lends itself to turning, several setups on a VMC proved more effective in this application, thanks largely to what Matt Sellers calls “creative programming.”

Capability to index parts can be particularly useful when features must be located in precise positions relative to one another, as was the case in one recent job involving a shaft with a series of outer-diameter set-screw holes. Even with an experienced eye and the aid of an angle finder, rotating the workpiece by hand took too long, and the risk of location error was too high. Indexing the part incrementally with the rotary fourth axis “takes the employee out of the equation,” Sellers says.

Fixtures Come First

For most work on the VMCs, reducing setup times is an exercise in strategizing about workholding. “We try to eliminate as much fixturing as we can,” Sellers says, although there are always exceptions. For example, the shop might use a milling machine as an alternative to a turning machine for larger, cylindrical parts that might generate chatter while spinning against a turning tool. In these cases, using additional fixtures to secure a part mounted in the fourth-axis indexer can be more effective.

For this square part, machining aluminum jaws to seat the flange and mount the part in a live-tool lathe chuck resulted in smoother surface and shorter time than would have been achieved on a VMC.

Conversely, parts that seem like obvious candidates for milling might actually be better candidates for turning. For example, turning tools tend to leave steel and stainless steel surfaces smoother than milling tools, Sellers says. Generally, turning such parts also requires using fewer tools.

Unsurprisingly for this shop, setup reduction is a more common reason for using a lathe when a VMC seems like a more obvious choice. For example, milling out aluminum chuck jaws to accommodate a square casting can be easier and faster than creating a fixture for milling the part itself. “You close (the chuck) with a foot pedal, and the part is secure,” he says.

This 17-4 stainless steel valve stem was among the first parts to benefit from production on a lathe with a Y-axis, live-tool turret. Cycle time dropped from 18 to 7 minutes. Setup takes 1.5 hours on the lathe versus 6 with the previous process, which required four setups on two machines (diameter turning and parting on a lathe; milling the flats on a VMC; threading on the lathe; and drilling holes and stem-head flats on the VMC).

Variation Is the Enemy of Efficiency

Underlying Kustom’s approach is a deeper principle than time savings. Chucking a part rather than carefully securing it in a more complex fixture; letting the machine itself probe the part or move the tailstock; and leaving common tools in their stations are all examples of limiting human involvement, and, by extension, the potential for variation in the process. A more standardized, repeatable process is both easier to learn and easier to execute. The net effect is to free the kind of capacity that matters most: human talent.

Related Content

4 Commonly Misapplied CNC Features

Misapplication of these important CNC features will result in wasted time, wasted or duplicated effort and/or wasted material.

Read More3 Tips to Accelerate Production on Swiss Lathes with Micro Tools

Low RPM lathes can cause tool breakage and prevent you from achieving proper SFM, but live tooling can provide an economical solution for these problems that can accelerate production.

Read MoreOkuma Demonstrates Different Perspectives on Automation

Several machine tools featured at Okuma’s 2023 Technology Showcase included different forms automation, from robots to gantry loaders to pallet changers.

Read MoreFinding the Right Tools for a Turning Shop

Xcelicut is a startup shop that has grown thanks to the right machines, cutting tools, grants and other resources.

Read MoreRead Next

Setting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)