Reinventing The Robot For The Job Shop

A compact robot that rolls out of the way when not needed/wanted provides the perfect solution to this shop's automation needs.

Share

Sequoia Automatic, Inc., a CNC precision machining shop in Crystal Lake, Illinois, needed to cut costs and improve efficiency to stay competitive as a second- and third-tier parts supplier to the automotive industry. Automation, in the form of small, compact robots designed to load/unload the shop's dual-pallet vertical machining centers (VMCs), is providing the answer to the firm's problems. Management sees the robots as the key to a potential five-fold increase in productivity for the shop.

Sequoia Automatic specializes in auto air conditioning system connectors, machining them from near-net-shape blanks sawed from extruded aluminum bars. The connectors are typically small—fitting within a 2- to 2 1/2-inch cube—and are machined in multiple-part fixtures on VMCs. Machining consists almost exclusively of bores and other internal features; the profile of the blank is usually left as extruded.

The shop has 34 VMCs, most of which are equipped with indexing tables. Because cycle times are long for a fixture-full of parts, one operator typically tends two VMCs. Despite the labor cost savings, the machining centers became less competitive over time, compared to rotary transfer machines operated by Sequoia Automatic's competition, for example.

In an attempt to improve productivity, the shop began replacing some of its older VMCs with VMCs equipped with dual pallets. "The older machines would sit idle while the operator removed finished parts from the fixture and replaced them with fresh blanks," explains Dennis J. Burke, the firm's general manager. "To eliminate the idle time, we started replacing some of the older machines with dual-pallet machines that allow the operator to load/unload parts from a fixture on one pallet while the parts in the fixture on the other pallet are being machined. Over the last 4 years, we purchased seven dual-pallet VMCs, and we were able to limit idle time on those machines to the few seconds that it takes them to switch pallets."

While the dual-pallet machines were a step in the right direction, still more improvement was needed. "Thanks to the global economy, we're not only competing with the shop down the street, but also with firms in South America, India, England . . . the world," adds Cheryl Schraut, head of quality control for the firm. "It was getting more and more costly to have operators at every machine, and it became obvious that we had to find some way to automate the machining process. Problem was—is—that we are a job shop and don't have many long-running jobs. Our challenge, therefore, was to automate processes that don't readily lend themselves to automation."

Automate How?

Mr. Burke anticipated that robotics offered the best solution for automating his shop's machining operations, although he was not sure what type of robot would be best for the job. He knew what he did not want, however. The volatility of the automotive part-manufacturing business is such that shops can and do abruptly lose jobs. Mr. Burke's worst nightmare involves installing large, expensive, stationary robots in order to automate large machining jobs, only to lose one or more of those jobs. The next part of the dream is even worse: scrambling to find similar jobs for the idled machining centers and robots. The horror continues: because the idled robots are anchored in front of, and block access to, the machines, the latter cannot even be loaded and unloaded manually by an operator for short-run jobs.

Mr. Burke researched a number of automation options, looking for the one most compatible with the shop's existing machines and processes. As options were considered and rejected, a profile of the most desirable robot started to emerge. The robot had to be small, light and cost effective. It would service one VMC, not several, and it would move out of the way when not being used to permit an operator to use the machine in a conventional manner, that is, to manually load and unload workpieces.

Unable to find such a robot in the marketplace, Sequoia asked its machine tool distributor, Yamazen Inc., (Schaumburg, Illinois), for ideas. Yamazen suggested that the shop discuss its robot needs with Fanuc Robotics America, Inc. (Rochester Hills, Michigan). A meeting was arranged at which Sequoia Automatic's Mr. Burke described his vision of the perfect robot to Gary Kowalski, district manager-sales for Fanuc Robotics Midwest. Mr. Kowalski listened, nodded his understanding of the shop's specific needs, and went away.

Mr. Kowalski revisited Sequoia Automatic several months later. He had a wooden model of a small, light, cost effective robot, designed to serve a single machine, that could be rolled to the side to provide easy access to the machine. Mr. Burke recalls his reaction to the model as love at first sight.

Sequoia Automatic agreed to purchase the first two production models of the robot, the Fanuc CNC Mate 200i, from Yamazen as part of a turnkey package that included two NTC America Corp. (Farmington Hills, Michigan) Model NV4G CNC vertical machining centers with dual pallets, and multiple-part workholding fixtures, for a large order that the shop had just received.

Fanuc designed the Mate 200i as a compact, low-cost solution to machine tending. Developed as a complete package and ready for interface to a machine tool, the self-contained unit includes a six-axis robot with a 19-inch reach. The robot can service lathes, mills, machining centers and other machines with load heights ranging from 36 to 44 inches from the floor. The robot's light weight (only 1,050 pounds) enables it to be picked up with a lift truck and delivered to any compatible machine within the plant, accessibility permitting.

A Few Feet

Sequoia Automatic needs to move its robots only a few feet to the side to access the machines they serve, and they are designed to do just that. The robot arm is mounted on a platform that rolls right or left to move it toward or away from the machine's part-loading zone. The right side of the protective enclosure moves with the platform, telescoping into the left side of the enclosure. When the platform is fully extended to the right so that the robot is in front of the part-loading zone, the enclosure occupies a 3- by 7-foot area; when retracted to the left, the footprint shrinks to approximately 3 by 4 feet.

Moving the robot away from the machine involves disengaging two locking pins and sliding the robot to the left. To reposition the robot in front of the machine's part-loading zone, the attendant slides the robot back into position, engages the locking pins on the enclosure panels, screws down the mounting pads on the platform legs until they reach the floor, and the robot is ready to go to work.

Sequoia Automatic is currently using both of its new, robot-loaded, dual-pallet VMCs to process an automobile air conditioning system connector that requires machining of both sides of the part. Each VMC machines both sides of the parts. The VMCs are positioned side by side, as seen in the photo on page 71. A third, manually loaded, dual-pallet VMC is also visible in the background. In addition to manually loading/unloading the pallets on his machine, the operator is also responsible for keeping the magazines of the robot-loaded VMCs filled with blanks.

Machining Sequence

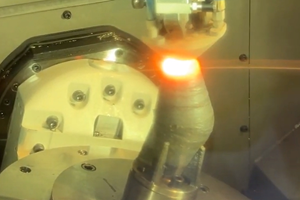

The machining of the connectors begins with the robot removing an extruded blank from the pick-up station at the foot of the workpiece magazines and delivering it to one of the pockets of a hydraulically actuated, multiple-part, workholding fixture mounted on the VMCs idle pallet (as shown on page 70). The loading continues until there is a blank in each of the workholding fixture's 12 pockets. The fixture then clamps the blanks to precisely locate and securely hold them for machining.

The door of the VMC opens and the pallets switch positions, carrying the loaded fixture into the machining area. As machining of the first side of the parts takes place, the robot loads more blanks into a second, identical fixture on the idle pallet. When machining of the first side of the blanks ends, the pallets again change positions. The robot removes the first-side-machined parts from the first pallet and delivers them to a "flip station" within the robot enclosure, loading them into the station from the inboard side. As soon as a fixture becomes available, the robot loads it with the first-side-machined parts. The robot retrieves the parts from the outboard side of the flip station (see Figure 1), which effectively "flips" or turns over the parts so that when they are reloaded in the fixture their unmachined sides face up.

After all 12 first-side-machined parts are reloaded in the fixture, the pallets change positions again, and the second-side machining begins. The pallet containing the now completely machined parts changes position still again to present them to the robot for unloading.

Before the robot removes the finished parts, however, it blows off the entire fixture using a high velocity air nozzle mounted on its gripper base (see Figure 2). The purpose of the procedure is to purge the fixture of any stray chips that might fall into one or more of the pockets when the parts are being unloaded and interfere with proper seating of the next batch of parts. Finally, the robot removes the completely machined connectors and delivers them to a finished parts chute. The cycle, from loading of the blank for first-side machining to delivery of the completely machined parts to the parts chute, takes approximately 30 minutes.

Assessing The Impact

The two robots are Sequoia Automatic's first experience with the technology. The company is very aware that it is just getting started with robots and that it has much to learn in the months and years ahead. However, it has already identified a number of improvements. Here are some of the more important ones:

Significantly improved uptime. By using robots to load/unload its two newest dual-pallet machining centers, the company is experiencing almost no downtime to load and unload those machines. The robots never hold up the machining centers. Except for the brief intervals to exchange pallets, there is always a tool in the cut. (Yes, there is tool change time, but it is a relatively minor consideration.)

"Dual-pallet machining centers generally deliver more uptime than machines with conventional tables, even when loaded and unloaded by an operator," concedes Mr. Burke. "However, the operator is frequently distracted, searching for a gage, looking for a replacement for a broken tool, on break, at lunch . . . so that the machine is frequently idle. Uptime seldom gets above 75 percent. On the other hand, the robot is always there, loading fresh blanks and removing finished parts without a break, making possible machine uptimes as high as 95 percent. We estimate that we're getting a 20 percent increase in machine uptime with the robots compared to machines that are loaded/unloaded manually."

Greater Productivity. In addition to achieving greater uptime with its new robot-served VMCs, Sequoia Automatic started getting improved productivity. Historically, the shop was staffed based on an operator at every machine. As the need to cut labor costs increased, ways were found for operators to run two machines.

When the newest robot-served machines were installed, the shop discovered that one operator could service both machines and still operate a nearby dual-pallet VMC that required manual loading and unloading. This is due largely to the fact that the robot's magazines hold enough blanks so that the VMCs can run largely unattended for up to 4 hours. Exploring ways to exploit the ability of the robots to feed the VMCs over long periods, the shop has begun experimenting with a two-shift arrangement for the two robot-served VMCs, with 4 hours of unattended machining between shifts. The arrangement provides the equivalent of three shifts worth of production using only two shifts of operators.

Some of the shop's veteran operators have estimated that they would be able to tend as many as six VMCs served by robots. That's not going to happen overnight, because the scenario envisions robots loading/unloading dual-pallet VMCs and the majority of Sequoia Automatic's VMCs have conventional worktables. The prospect can become a reality over time, however; the shop can gradually add more robots and dual-pallet VMCs until it achieves the degree of automation it needs to stay competitive. The strategy also offers a gradual path for growth.

Greater consistency. "The nice thing about a robot is that once you get it working well, it does the same thing every time," muses Sequoia Automatic's Cheryl Schraut. "When you remove variation from the process, you improve results. When we went to robot load with our new machines, the cpk for the job went from 1.3 to 1.9, which is a significant improvement. The higher the number, the better your process is performing. That's the kind of quality we must have to remain competitive.

"When you eliminate variability in one area, you often achieve improvements in others," Ms. Schraut continues. "For example, loading of parts in the fixture by hand has been a frequent source of problems. The operator would mis-clamp one of the parts, which would result in a broken tool. Now, robot loading of the parts into hydraulic fixtures has eliminated that problem. We're no longer breaking tools because of operator errors. Before, tool breakage, not wear, accounted for most of our tooling costs. Now, tools are lasting for months, and tool life has become more predictable. Also, with robot loading and unloading, we're reducing the danger of operator mishaps that can cause damage to the machining centers. For example, it saves us having to pay $15,000 to replace a spindle that was damaged because an operator forgot to tighten a 10-cent nut. "

Compensation for skilled labor shortages. "It's easier to find employees willing to run several robots than it is to find a worker willing to load and unload a machine tool all day long," Mr. Burke adds. "Skilled workers are in great demand, and it's difficult to find the right people. We can offer potential employees jobs where they can be working with the latest technology, such as CNC machine tools, computers, SPC—and now robots. We can sell ‘thinking jobs' to prospective employees; it's harder to sell non-thinking, monotonous jobs."

More To Come

Mr. Burke reports that Sequoia Automatic will be purchasing one or two more robots this year for installation on the shop's other dual-pallet VMCs. He's convinced that the combination of VMCs and robot load/unload makes the shop more competitive for intermediate-volume jobs (400,000 to 750,000 pieces) than shops that would run such jobs on rotary transfer machines and similar equipment better suited to higher part volumes (1,000,000 pieces and up). And he always has the option of moving the robot aside and running the job manually. "We can't expect our customers to pay more just because we have only one way of doing things," Mr. Burke explains. "With our existing arrangement, I can simply move the automation out of the way and run the job manually. "

The shop's new robots will look different from the ones currently installed in the shop. The original enclosures, consisting of Plexiglas panels in extruded aluminum frames, have been replaced by more conventional sheet metal panels with smaller Plexiglas windows in the newer models.

Mr. Burke has a suggestion for shops thinking about automating their operations with robots. "From the onset, our goal in automating was not to eliminate jobs, but to increase the productivity of our workforce by giving them better tools," he stresses. "People, not equipment, make companies. When you start planning to install robots, some of your employees are going to worry that they might lose their jobs. You need to stress to your employees that the company is investing in automation to grow by being better able to serve its customers' needs. They need to be assured that the robots are there to help them do a better job, and that in the long run, the robots will help them keep their jobs."

Related Content

How a Custom ERP System Drives Automation in Large-Format Machining

Part of Major Tool’s 52,000 square-foot building expansion includes the installation of this new Waldrich Coburg Taurus 30 vertical machining center.

Read MoreIn Moldmaking, Mantle Process Addresses Lead Time and Talent Pool

A new process delivered through what looks like a standard machining center promises to streamline machining of injection mold cores and cavities and even answer the declining availability of toolmakers.

Read MoreLean Approach to Automated Machine Tending Delivers Quicker Paths to Success

Almost any shop can automate at least some of its production, even in low-volume, high-mix applications. The key to getting started is finding the simplest solutions that fit your requirements. It helps to work with an automation partner that understands your needs.

Read MoreAdditive/Subtractive Hybrid CNC Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Read MoreRead Next

Manufacturer Takes Innovative Approach To Advanced Manufacturing Processes

Thousands of contract manufacturing shops across North America that produce commodity parts such as shafts, arbors, bearing races, gear splines, and so on, have one problem in common: how to do it faster and less expensively.

Read MoreAn Approach To Boosting Shop Production Capacity

The increased availability of modular manufacturing cells has added another means of increasing a shop’s capacity. This article looks at a practical approach to evaluating when and how much automation is appropriate for a shop.

Read MoreCNC Robotics And Automation: Knowing When To Say 'When'

In metalworking, a shop's move from one level of automation to the next can be a business-busting decision if badly timed. This article looks at what you should consider when taking the next step toward automating an operation.

Read More