Additive/Subtractive Hybrid CNC Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Share

The hybrid CNC machine tool is an idea that continues to advance.

This is worth seeing. The term, “hybrid,” refers to a machine tool that is also something more — usually it connotes combining additive manufacturing (AM) and the machine tool’s normal work of “subtractive” machining within a single machine able to mix both operations in a single cycle. As a working concept, the idea is a decade old. Applications are not so widespread that hybrid machines are found in typical job shops, but applications are numerous enough to offer an expanding market that continues to be served. The hybrid machine tool is, in one sense, a niche technology. In another sense, it is something more, because there is a diversity of niches in which the technology offers promise.

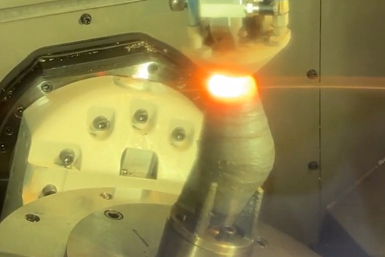

View of a metal 3D printing operation on a hybrid machine tool from Mazak. This shot is a still from the video below on the hypersonic missile nosecone.

At a distance, the hybrid machine tool seems just provocatively useful. The machine offers the chance to begin with an empty work zone, and not only create a part the way a 3D printer can, but also machine it to its required tolerances as part of the same cycle. Considered more closely, the hybrid model poses some challenges. But the matter of when to use a hybrid and what it can do is not at an end. In the last several years, I have seen at least two major developments that seem to me to have opened wider the extent of how useful a hybrid machine can be.

First, the limitations. The hybrid idea inherently means one machine carries the capabilities of two, but puts only one set of capabilities to work in any moment. The potential for process imbalance thus means the machine, while versatile, is not necessarily efficient for a given application. A part made complete using metal 3D printing and machining might require only one-third as much machining time as the 3D printing. This being the case, it is possible that two or three single-purpose AM machines used in tandem with one single-purpose CNC machine tool might provide a faster and cheaper solution if the use is recurring production.

This limitation is why cladding and repair are two applications in which hybrid often is an attractive choice. Cladding does not involve 3D printing a complete form that also needs machining, but instead involves adding a layer of material to a surface ahead of machining. Additive and machining time are balanced enough that one is not kept waiting long within the shared cycle. Something similar is true of using a hybrid machine to repair a valuable tool or part: Restoring the worn or damaged feature calls on both 3D printing and machining, using them both nearly enough in balance and in tandem that the hybrid machine is far more capable and efficient than trying to perform the same repair through multiple separate operations and setups.

Another limitation, or at least a consideration, is this: Hybrid machine tools performing 3D printing generally do so through laser metal deposition, meaning the machine shop adding this type of machine must add laser melting to its mix, likely an unfamiliar capability. Some hybrid machines also employ powder metal as the material stock, which, for the typical shop, is apt to be an unfamiliar material choice with new safety considerations to accommodate. Yet this latter detail points to one of the developments of the past several years that I see bolstering hybrid’s promise. Namely, wire-fed deposition systems arrived as an additional option. The laser is still there as a new system to learn, but spools of wire are a much easier form of metal stock to handle and manage.

Here is the other major development that I see helping hybrid: The COVID pandemic and its effects on logistics and supply turned seemingly all manufacturers’ attention to their supply chains. Steps such as casting or assembly might add considerable lead time, complexity or supplier vulnerability to a given product’s process, and the impact of this is now seen and questioned to a greater extent than it was just a few years ago. A hybrid machine can overcome casting by making the part from scratch; it can overcome assembly by allowing machining to generate precise internal features of a complex form as the part is being built. Where quantities are low enough, the chance to bypass casting or assembly in this way is potentially valuable enough to overlook any cycle time inefficiency in the machine that can deliver this simplified, responsive, on-demand part making.

And this is where we are now. Hybrid is an option for cladding and repair, and we should watch for its application to expand as an option for complete parts as a workaround for steps that might otherwise involve time or complexity. The two major developments I cite are interrelated, since we should not discount the ease and safety of material use as a factor aiding adoption as a supply chain solution. An extreme case: The Navy warship USS Bataan now carries a hybrid machining center with wire feedstock as a method of manufacturing replacement parts as needed while the ship is at sea.

Then there is still more related to brand new markets, and new possibilities. Again, the term “hybrid” refers to a machine tool that is also something more — usually additive manufacturing, but perhaps some other capability. Machine tool builder Mazak, for example, makes hybrid machine tools combining machining with friction stir welding. One promising market is electric vehicles. The battery trays of these vehicles need to be sealed; traditional welding’s heat risks damaging the battery. Mazak executives say various major automakers are therefore evaluating friction stir welding hybrid machines tools as an alternative, not just to reliably and precisely seal the battery compartments in a joining process not using heat, but then also, as an added benefit, to go on to machine those battery compartments to tolerance within the same cycle and setup.

Learn more about friction stir welding in the playlist of related video below.

Related Content

Lean Approach to Automated Machine Tending Delivers Quicker Paths to Success

Almost any shop can automate at least some of its production, even in low-volume, high-mix applications. The key to getting started is finding the simplest solutions that fit your requirements. It helps to work with an automation partner that understands your needs.

Read MoreThe Benefits of In-House Toolmaking

The addition of two larger gantry routers has enabled a maker of rubber belting products to produce more tooling in-house, reducing lead times and costs for itself and its sister facilities.

Read MoreDN Solutions' VMC Provides Diverse Five-Axis Machining

The company’s DVF Series comprises compact five-axis CNC machines that are designed for diverse five-sided or simultaneous five-axis applications.

Read MoreHow a Custom ERP System Drives Automation in Large-Format Machining

Part of Major Tool’s 52,000 square-foot building expansion includes the installation of this new Waldrich Coburg Taurus 30 vertical machining center.

Read MoreRead Next

Registration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More