Presetting Becomes Prevalent

Next Intent implemented presetting and shrink-fit toolholding when it bought a five-axis machining center, but it has since seen these resources deliver value to machining centers throughout the shop.

Share

How much time is tool presetting saving for Next Intent, a defense and aerospace contract manufacturer in San Luis Obispo, Calif.?

That’s hard to say.

Today, the offset measurements for cutting tools used in this shop’s machining centers are obtained away from the machine. Each tool-and-toolholder assembly is measured in seconds at the presetter, without the machining center being interrupted. That is a big change from the way the shop’s staff is accustomed to measuring tools. The measurements used to be made at the machine tool, with the tool in the spindle, where the measurement might take 2 to 3 minutes per tool. To set up a job involving a large number of cutters, nearly an hour of potential machining time could be lost just on obtaining tool offsets.

However, that is not as large of an impact as it might seem. Not every job requires that many tools. And many jobs run for a long time, meaning that even an hour of lost machining is a relatively small cost.

Plus, Next Intent is a business focused on unusual manufacturing challenges. Wringing incremental savings out of general production is not the company’s primary focus.

For all of these reasons, the husband-and-wife owners, company President and CEO Rodney Babcock and CFO Cayse Babcock, hesitated to invest in a presetter system. A presetter that would be fast and sophisticated enough to support all of the machining centers in the shop would, itself, cost as much as a small CNC machine. The owners knew it would deliver value in terms of freed-up machine capacity, but would it deliver enough added capacity to justify the expense?

They are pretty sure the answer proved to be yes, Mr. Babcock says. The shop now uses a Smile 400 presetter system from Zoller as a routine part of its process. Precise payback is hard to demonstrate, because there are enough variables in this shop’s mix of work that the hard numbers quantifying this are not available. But what Mr. Babcock does have is the daily sight of how well the shop now moves.

Obtaining tool offsets used to be the time-consuming work of a craftsman taking careful measurements at the machine, he says. Skill was needed for each tool dimension measured. The company’s machinists are so skilled, and value their work so personally, that he thought they would be protective of this vital step. If so, it was worth paying a little machine time to allow this.

By contrast, obtaining tool offsets is now a fast and easy step. Because tool measurements are made away from the machine, a machinist can perform this step for the upcoming job while the current job is being cut. Using programs the shop has written for the presetter, recurring tools can be measured automatically. As a result, the machinists have come to appreciate presetting for the same reason Mr. Babcock does. Namely, the entire procession from job to job now moves more fluidly, with less of an uncertain pause in between. That’s why the company president now says, “We probably should have done this two years earlier.”

CHARGE FOR CHALLENGING WORK

The presetter came at the same time as another recent purchase, a five-axis machining center. The company specializes in relatively high-value work, which often proves to be high-profile as well. It has machined parts for the Mars Curiosity Rover, the Antares Rocket, Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo and the Discovery Channel Telescope. It also routinely works in unusual aerospace alloys, titanium 10V-2Fe-3Al being one example. But despite the aerospace focus and despite the complexity of many of the components it produces, a machine dedicated to five-axis milling is a new addition here. Historically, the shop has had roughly the same array of machine tools that users of high-end CNC equipment across many industries might also employ. In five-axis machining, a VMC with a tilting rotary table was sufficient for the shop’s needs for quite a while. Instead of equipment assets, Mr. Babcock says the factor that actually distinguishes his shop—and this is an important point—is intellectual property.

Vibration isolators illustrate this. These are machined components that mitigate vibration within aircraft and spacecraft, protecting a sensitive instrument during a rocket launch, for example. Each isolator is essentially a complex spring machined in one piece out of a solid block of titanium alloy or steel. Because stiffness and damping properties are precisely engineered, the isolator’s dimensions have to be precisely controlled, including protecting the part from distortions that might result from spring-back after either external clamps or stresses within the part are released. Next Intent wins this kind of work because the company has invested in developing knowledge related to the workholding, tooling and toolpath strategies that enable these unusual parts to be machined reliably and productively.

Developing this knowledge truly is an investment, Mr. Babcock says. The customer is not well served if the shop cannot obtain the resources to pursue this understanding of how best to produce the parts. The mistake he thinks many machining businesses make is that they do not charge enough for challenging work. Next Intent succeeds because it does charge enough, he says, and over time, the company has won the trust of customers willing to pay rates commensurate with machining work that demands a potentially costly intellectual investment.

That strategy generally gives the shop the capital it needs to obtain appropriate equipment as warranted. However, this same strategy—developing process knowledge and proprietary techniques on its existing equipment—also allows the shop to be cautious in making such investments, for better or worse.

When the company decided to advance its five-axis machining capabilities, the machining center it chose was a VC-X350 from OKK. This would become the most expensive machining center in the shop. Relative to other machines, therefore, it seemed particularly important for the shop to make the highest possible percentage of this machine’s time available for production. Presetting tools offline, as opposed to measuring tools at the machine, clearly offered a way to do this. The prospect of also applying presetting to the shop’s other machining centers only strengthened the case for this investment. The only flaw in this thinking, if it could be called a flaw, is that the logic of a presetter actually did not demand a machine as valuable as the new five-axis.

Next Intent had previous experience with a presetter winning acceptance and delivering value beyond what was expected. This experience was the basis for the company’s hope that a more advanced presetter would be readily accepted as well. But in fact, the new presetter was accepted into use even more readily and rapidly than the shop had anticipated, quickly becoming a natural part of the shop’s processes. Now, setup moves more quickly for all of the shop’s machining centers, and this shop-wide value of presetting has proven to be more significant than the intended benefit of getting the most value out of the new five-axis machine.

PRESETTING’S PREVIEW

That first experience with presetting involved a second Next Intent machine shop in a separate building on the same property as the main facility. This second shop was opened and equipped with two CNC machining centers and a CNC lathe in preparation for a long-term special project with one of the company’s customers. The special project never happened, but the company went on to find other business for this second shop and the machines within it. What did happen was the surprise related to presetting. The special project would have involved machining various critical bores, so the company equipped the second shop with an economical presetter from Elbo Controlli as a means for efficiently measuring and setting boring heads. Measuring tools this way proved so easy that the operators in the smaller shop soon took to using the presetter to measure all machining center tooling. The presetter is still there, and the staff of this small shop still uses it routinely.

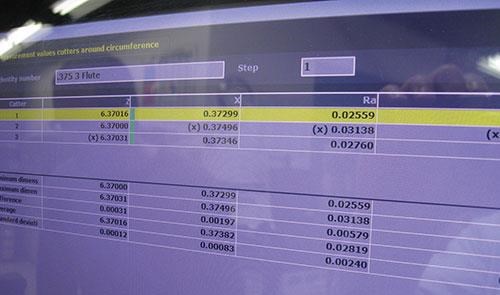

The main shop is much larger, with many more machines. To support it, the company bought a programmable presetter system from Zoller, which has enabled the shop to develop various measurement programs for capturing necessary tool data at the push of a button for tools it uses routinely. In addition, the system’s graphic presentation of the data reveals potentially costly problems that might otherwise go unseen, such as when one flute of an end mill is sufficiently different from the other flutes that the entire tool should not be used in a critical operation.

When this presetter completes its measurement of a tool-and-toolholder assembly, it generates a label that lets the operator loading that tool in the machining center know precisely what offsets to enter at the control. An even more efficient option would involve networking the presetter and the CNCs together so that offsets are transferred digitally, but Next Intent has not yet gone that far. For now, the paper labels seem to be working well.

There was also another tool-management investment. Presetting was arguably just half of a tool-management solution the shop has now put in place. Along with the system for measuring tool-and-toolholder assemblies came a change in the way the shop creates some of those assemblies. At the same time it bought the presetter, the shop also invested in shrink-fit toolholding.

RUNOUT AND RIGIDITY

The investment in shrink-fit consisted of a Power Clamp heating unit from Haimer, along with various shrink-fit toolholders. Here again, the five-axis machining center provided the justification. For the intricate milling this machine would be doing, the shop thought it ought to have tooling with the most precise runout possible.

But here again, that value, once it was obtained, proved valuable for existing machining centers as well.

One of these was the VMC with the tilting rotary table, the machine on which the shop had previously run its five-axis work. When shrink-fit holders were used to take milling passes on this machine, the secure hold and tight concentricity produced surface finish superior to what had previously been achieved. In essence, this machine had potential for precision that had previously gone unrealized. That is why, while presetting saves time for the shop, the value of shrink-fit might be even more transformational. A particularly memorable moment in titanium 10V-2Fe-3Al illustrates this.

The alloy is used in aircraft applications where the need to reduce weight is particularly urgent or critical. One of the disadvantages that make this metal so costly is the difficulty machining it. Next Intent seeks to save some of this cost by investing in extensive test cutting to learn how quickly it can machine the metal. In one aggressive cut in this metal with a milling tool held in a set-screw holder, the tool broke precisely at the point of the Weldon flat. Dale Bruce, Next Intent senior CNC machinist, says this was the tool’s failure point because of the toolholder design. The bore of a set-screw holder has to be oversize relative to the tool shank so that the tool has clearance to slide in. Because of that clearance, he says, the screw contact on the flat is the area where the tool is actually secured.

By contrast, a shrink-fit holder has a bore diameter exactly the same as the diameter of the tool shank. Thermal contraction ensures this—the toolholder shrinks around the tool. Thus, the tool is thoroughly clamped not only along its shank but also all around the circumference. The result is not only tighter runout, but also a stronger grip. Mr. Bruce says Next Intent is still in the process of discovering just how much more productively it can mill challenging alloys today, thanks to this toolholding change.

EASE OF ADOPTION

So far, there is no dedicated tooling manager at Next Intent who assembles tools and toolholders at the shrink-fit unit and measures them using the presetter, though that idea is being discussed. Instead, the machinists at Next Intent all individually use shrink-fit and presetting, just as they all formerly measured their own tool offsets at the individual machines.

Was this staff-wide change difficult to implement? One might expect it to be particularly difficult in a shop so committed to cultivating the value of intellectual property. IP consists of knowledge won by people, so an appreciation for IP is inherently an appreciation for the value of talented individuals. Was it difficult to persuade all of these people to make this change?

Mr. Babcock says the transition was quick and smooth. It is true that people are creatures of habit. Everyone—all of us—is biased into believing that the way we are accustomed to doing something is the best way to do it. As a result, persuasion was needed, he says. If employees were left solely to their comfort with measuring tool offsets at the machine, then there was a danger the presetter might have been left alone and adopted only slowly. Another relevant factor, he says, is that people resist being forced to change.

But conscientious professionals want the chance to work better and produce more, and Mr. Babcock hoped they would see the new tool-management resources this way. To that end, he began by letting the most senior employees in the shop explore what they could do with the capabilities of both presetting and shrink-fit. They then instructed others in how to achieve the same successes they were realizing.

Presetting in particular was a big change for Next Intent, but to those who used it, it rapidly came to seem like the most natural way to set up tools.

Learn more about Koma Precision.

Related Content

Workholding Fixtures Save Over 4,500 Hours of Labor Annually

All World Machinery Supply designs each fixture to minimize the number of operations, resulting in reduced handling and idle spindle time.

Read MoreHow I Made It: Amy Skrzypczak, CNC Machinist, Westminster Tool

At just 28 years old, Amy Skrzypczak is already logging her ninth year as a CNC machinist. While during high school Skrzypczak may not have guessed that she’d soon be running an electrical discharge machining (EDM) department, after attending her local community college she found a home among the “misfits” at Westminster Tool. Today, she oversees the company’s wire EDM operations and feels grateful to have avoided more well-worn career paths.

Read MoreManufacturing Madness: Colleges Vie for Machining Title (Includes Video)

The first annual SEC Machining Competition highlighted students studying for careers in machining, as well as the need to rebuild a domestic manufacturing workforce.

Read MoreBuilding Machines and Apprenticeships In-House: 5-Axis Live

Universal machines were the main draw of Grob’s 5-Axis Live — though the company’s apprenticeship and support proved equally impressive.

Read MoreRead Next

Slideshow: Vibration Isolators

An aerospace shop shows further examples of complex machined parts used to mitigate vibration.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More