Not Just a CNC Degree

A relationship with a local employer allowed Rock Valley College to create a 21st-century model for manufacturing instruction. That was good, because for this school’s manufacturing program, the 20th century did not end well.

Share

Something happened around the year 2000. Manufacturing education has not been the same since.

You might recall that this was the period when it became apparent that a significant amount of manufacturing work was being sent overseas. Offshoring had been happening for years, and it’s still happening today, but around 2000 is when the public became widely aware of the phenomenon, partly because offshoring activity was so high. The pullback that we would call “reshoring” was still in the future. Back then, the shift of manufacturing to low-wage countries seemed relentless.

Thomas Clark was doing the work then that he still does today. The associate professor of engineering and technology teaches manufacturing students at Rock Valley College (RVC) in Rockford, Illinois. Around the century’s end, he says, two serious developments affecting manufacturing education—both related to the development above—became apparent as well. One was a steep decline in enrollment from employees of local companies. Traditionally, manufacturing businesses had supported manufacturing-focused community college programs such as his by paying tuition for employees who enrolled as part-time students. Around 2000, the practice all but stopped. The assumption seemed to be that domestic manufacturing would be staffing down rather than staffing up.

The other change he saw was that parents became generally unwilling to see their children pursue manufacturing careers. One could hardly blame them. Manufacturers themselves seemed to be retreating from domestic manufacturing, and in the industrial city of Rockford, many of those parents no doubt had been laid off from manufacturing positions.

By 2005, Rock Valley College’s manufacturing engineering technology program was in danger of being eliminated.

But something else had also been happening. Manufacturers had eliminated their own internal training programs as well. Thus, essentially no one was adding new talent to the manufacturing labor pool. Employees let go from manufacturing moved into other fields. When manufacturing activity rebounded, plants in Rockford found themselves with too few prospective employees to hire.

That’s when one local company decided to dramatically change course. Woodward, a maker of aerospace and energy-industry components with a production plant in nearby Loves Park, came to RVC hoping to quickly ramp up a program that would ensure an ongoing pipeline of promising employee candidates. The company would pay tuition for program participants, who would work part-time at Woodward while carrying a full-time course load at RVC. Named for the college’s mascot, this program became “Golden Eagles Manufacturing,” or GEM. Recently the program was renamed “Launch.” Woodward has continued to support this program since its start in 2007, and other local manufacturers have also joined as sponsors of their own GEM or Launch students. Now, roughly half of RVC students seeking two-year degrees in manufacturing engineering technology or electrical engineering technology are funded by a Launch employer.

Mr. Clark says this development did more than rejuvenate manufacturing instruction at RVC; it led to its re-creation. For example, the very hours of activity changed. The manufacturers’ shift from subsidizing part-time students to subsidizing full-time ones produced dramatically more daytime students, where the majority of manufacturing classes used to be at night. However, the most significant change has been in the content of RVC’s instruction. This has been adapted to better prepare students for what a manufacturing career in the 21st century is likely to demand.

Facilities on Film

The college’s modern, well-equipped manufacturing facilities are worth seeing. In fact, you can see them—the college figures into a video recently produced to inform young people about studying manufacturing. As the film shows, RVC’s resources for manufacturing instruction include modern CAD classrooms, a machining lab with the CNC capacity of a thriving job shop, and a robot lab where students practice with three robots to achieve certification from FANUC Robotics.

The objective is something more than a CNC machining degree, Mr. Clark says. This is true for both Launch students and conventional students. He and the other educators who design the two-year-degree curriculum are continually challenged to include an expanding list of subjects that employers cite as important. In addition to CNC machining and robot programming, manufacturing students receive instruction in PLC programming, circuits and electronics (the manufacturing and electrical programs share several classes in common), and non-technical subject areas such as lean manufacturing, communication and working effectively on teams.

Focusing too extensively on just the technical skills that seem to be needed right now in the job market would be counterproductive, Mr. Clark says. Doing this would be a disservice to both students and employers, even though some employers press for this. The mix of manufacturing technologies will continue to change, he says, and companies will continue to adapt in the face of volatility. An employee wedded too tightly to today’s manufacturing processes is likely to be a candidate for layoff during the next major change. RVC’s goal instead is to produce manufacturing problem-solvers and lifelong learners—employees who have the technical foundation to shift into new roles at the same rate that manufacturing companies themselves are shifting and changing.

Employer Benefits

For the manufacturing companies that participate, the Launch program is a great bargain, Mr. Clark says. Arguably, it is a far better bargain than what the companies previously received by giving full-time employees the option of attending college at night.

In the Launch model, the student’s paid studies and part-time job are mutually connected. This pressures the student to perform acceptably at each or risk losing both. (A student earning below a C in any course is financially responsible for that course.) Meanwhile, the part-time workers’ wages are low for the quality of work these employees can provide. And at the end of the two-year commitment, while the sponsor company has the inside track to hiring the student, there is no formal or informal expectation of a job. For the price of two-year tuition, therefore, the Launch employer has the chance to vet a prospective employee through a long trial period, and also groom and condition this person to be ready to perform effectively on the first day of work after college, if he or she is indeed hired.

Understanding manufacturing is no longer a prerequisite for entering the program, Mr. Clark says. In fact, incoming students who imagine they are interested in manufacturing might be imagining something out of date. Students should be interested in both mental work and hands-on work, he says, and certainly they ought to enjoy math. But the Launch program’s promise of paid tuition attracts some students who might never have considered manufacturing before, and that’s by design. Many students grow to love the field as they discover all that it entails.

Work-study is essential to this discovery, he says. Providing work experience in parallel with academic learning is a key reason why the Launch program works, and why it produces employees valuable enough that companies keep returning to sponsor more students. He sees the work experience building not only knowledge, but also character.

Again, the program attracts many students who have never worked in manufacturing, including many who have little basis for understanding what the field will ask of them. Little clues reveal this, he says—casual signs of sloppiness or disrespect that are apparent in new students. But once the student starts working for a company, he says he sees the positive changes. On the job, the student acquires the many disciplines that are natural and necessary to manufacturing, including consistency, precision, attention to detail, commitment to safety, and appreciation for the properties of different materials. What other field can promise to impart all of this? Academic knowledge of manufacturing is one thing, he says, but actually working in manufacturing develops maturity—and that maturity is as valuable to employers as any particular skill.

Related Content

Same Headcount, Double the Sales: Successful Job Shop Automation

Doubling sales requires more than just robots. Pro Products’ staff works in tandem with robots, performing inspection and other value-added activities.

Read MoreSolve Worker Shortages With ACE Workforce Development

The America’s Cutting Edge (ACE) program is addressing the current shortage in trained and available workers by offering no-cost online and in-person training opportunities in CNC machining and metrology.

Read MoreThe Power of Practical Demonstrations and Projects

Practical work has served Bridgerland Technical College both in preparing its current students for manufacturing jobs and in appealing to new generations of potential machinists.

Read MoreBuilding Machines and Apprenticeships In-House: 5-Axis Live

Universal machines were the main draw of Grob’s 5-Axis Live — though the company’s apprenticeship and support proved equally impressive.

Read MoreRead Next

Video: What Is It Like to Study Manufacturing?

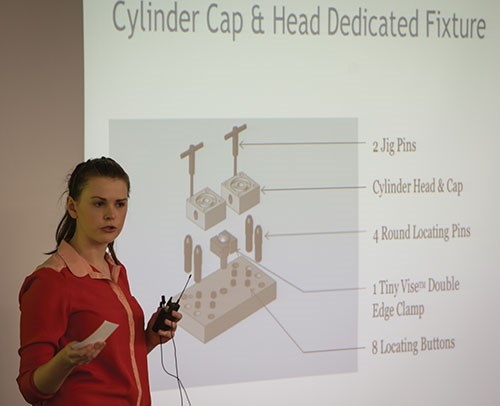

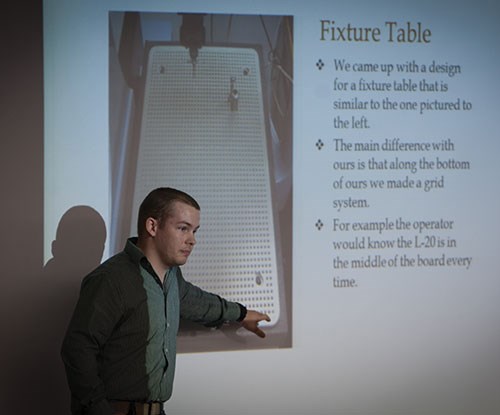

A student project team at a community college illustrates the learning and experience involved in preparing for a manufacturing career.

Read MoreVideo: Meet a Manufacturing Student

Rock Valley College student Sara McKee describes her interest in manufacturing and her study of manufacturing engineering technology.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)