How We Misread Productivity Gains in the Debate About Manufacturing Jobs

Manufacturing appears to lead other sectors in productivity growth, but productivity measures pick up factors besides automation. Recognizing this fact changes the terms of part of the public debate.

Share

The United States has lost about 5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000. Is that decline the result of automation, meaning the advance of technology, or trade, which responds to choices in public policy? Susan Houseman does not have the answer, but she says the terms of the debate get muddied. Arguments based on U.S. government manufacturing productivity metrics tend to misinterpret what those metrics measure. In U.S. manufacturing, she says, automation is not doing as much as some claim.

Dr. Houseman is VP and Director of Research with the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. She gave a talk on manufacturing employment at the most recent MTForecast conference, hosted by AMT–The Association For Manufacturing Technology. She says the problems with productivity numbers relate to the composition of domestic work as well as adjustment factors.

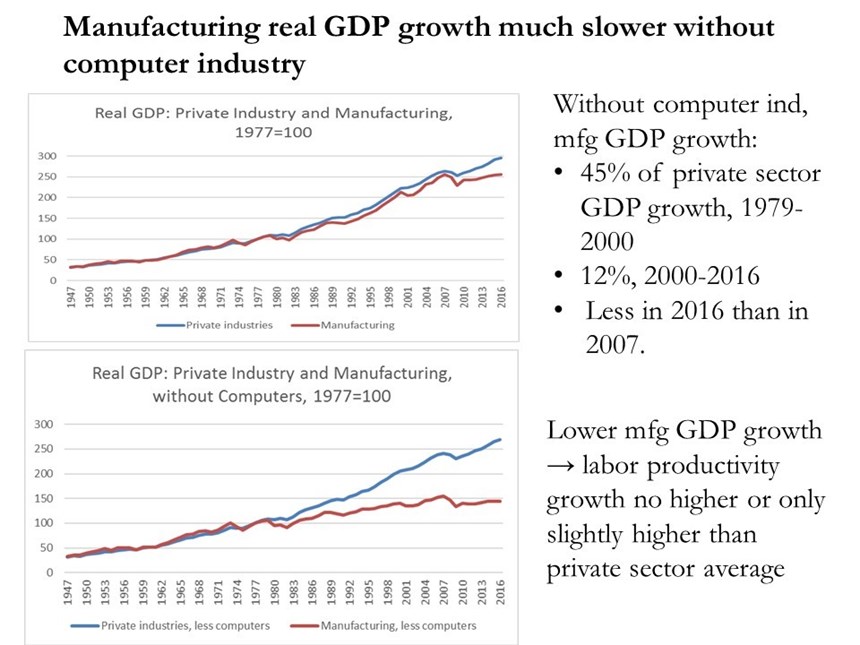

Here is the productivity-based argument that is often made: Manufacturing output, adjusted for inflation by government statistical agencies, has kept pace with gross domestic product growth for decades, even as employment declined. Manufacturing’s ability to keep producing the same or more stuff with fewer and fewer people thus shows that productivity growth has been greater in manufacturing than elsewhere in the economy. We have fewer employees in manufacturing because fewer are needed. Thank you, automation.

But hold on, Dr. Houseman says—automation is not the only, or even the primary, factor driving productivity growth. And the strong manufacturing output and productivity growth reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) are misleading.

For example, consider a product with many manufacturing steps in which the labor-intensive steps are outsourced to another country. The BEAfigure captures value added in the United States. After outsourcing, since there are fewer U.S. jobs relative to the value still added in the states, the “productivity” would appear to increase—solely because of the offshoring.

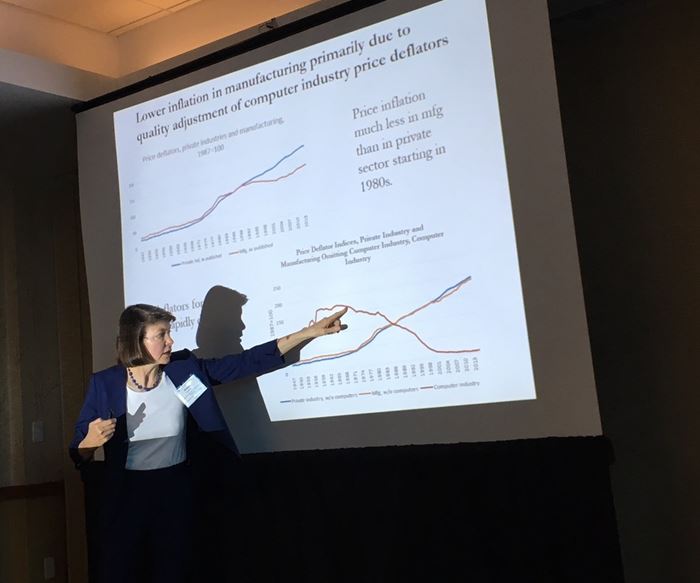

This effect is not even the most vexing, she says. An even greater problemcomes from the BLS’s attempt to maintain parity within product comparisons as those products steadily improve. A cell phone of 2005 is not the same as a cell phone of 2018, even if prices are similar. Nor is a car the same. In both categories, the government introduces adjustment factors to account for quality and capability improvements. However, the cumulative adjustments in the area of electronics have been so large that just these adjustments—not the quantity of items produced, mind you, just the adjustments for product quality improvements—have overwhelmed manufacturing output.

If BEA manufacturing figures are corrected simply to remove adjustment factors in one area, computers and semiconductors, then that change alone dramatically alters the comparison. Manufacturing productivity no longer shines after this adjustment. Productivity in manufacturing has still advanced, but only at about the same rate or slightly greater compared to productivity in other parts of the economy. Therefore, there is nothing distinctive about automation in manufacturing that brings something special to the discussion of jobs in manufacturing.

In other words, manufacturers still need people. That means, to a greater extent than we might have believed, the decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs has been a direct result of a decline or low growth in U.S. manufacturing.

Technology and trade both affect manufacturing, Dr. Houseman says. Both must be part of the public discussion. But thanks to the still-widespread misreading of productivity data, the effect of trade on U.S. manufacturing and U.S. manufacturing employment has been masked. We have spent years having a distorted public discussion that lets trade policy too far off the hook.

Related Content

Building Machines and Apprenticeships In-House: 5-Axis Live

Universal machines were the main draw of Grob’s 5-Axis Live — though the company’s apprenticeship and support proved equally impressive.

Read MoreAddressing the Manufacturing Labor Shortage Needs to Start Here

Student-run businesses focused on technical training for the trades are taking root across the U.S. Can we — should we — leverage their regional successes into a nationwide platform?

Read MoreDN Solutions Responds to Labor Shortages, Reshoring, the Automotive Industry and More

At its first in-person DIMF since 2019, DN Solutions showcased a range of new technologies, from automation to machine tools to software. President WJ Kim explains how these products are responses to changes within the company and the manufacturing industry as a whole.

Read MoreManufacturing Madness: Colleges Vie for Machining Title (Includes Video)

The first annual SEC Machining Competition highlighted students studying for careers in machining, as well as the need to rebuild a domestic manufacturing workforce.

Read MoreRead Next

5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More