Getting Started with Machine Monitoring

This shop’s successful entry into machine monitoring reveals important points about what to do and what to expect.

Share

Have you noticed that some of the skinniest, fittest people you know are now wearing watch-like devices to track their activities, such as the number of steps they take, the calories they burn and hours of sleep they get? Having this data at hand (or on the wrist, to be exact) increases their awareness of habits that promote a healthy lifestyle. Because they waste less time sitting around or not getting restful sleep, they tend to have leaner, stronger physiques—at least that is their goal.

In a real sense, manufacturing companies are thinking and moving along the same lines. Companies that are already practicing lean manufacturing techniques are turning to machine-monitoring systems to help them reinforce the habit of continually trimming down on activities that don’t add value for the customer.

For example, Richards Industries, a Cincinnati, Ohio, company that manufactures industrial valves, has been practicing lean manufacturing for many years. Now, it has installed a machine-monitoring system that is enabling shopfloor personnel to track activities and record the performance of its machine tools. Like readings from a Fitbit or Jawbone, the data gathered and analyzed by this system is making the company more aware of how well machine time and manpower count toward productivity.

Although Richards Industries is still in the early stages of implementing this machine-monitoring system, the results are encouraging. They show that the company is moving to a higher level of lean operation. Machine uptime has increased significantly; a pallet-changing system is getting better usage; CNC programs are running more efficiently; and setup procedures have been further streamlined.

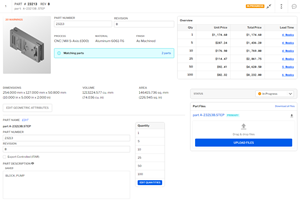

The valves and related products manufactured by Richards Industries are specially engineered for critical applications in a variety of industries, including chemical, petroleum, power generation, biotech and pharmaceutical. The company offers six distinct product lines that cover many types of specialty valves and related accessories, such as control valves, pressure regulators, instrument valves, manifolds, ball valves and steam traps. Most of these products, which are marketed globally, can be ordered as standard items, but the company offers customized variations that are engineered for critical or unusual applications.

Richards Industries has manufacturing facilities in Cincinnati (its headquarters), but also sources some items from China, India, Taiwan and other countries. All customized and engineered products are produced in Cincinnati. In the machining area, occupied by about 30 new and older CNC mills and lathes (and a few “legacy workhorses”), batch sizes are small. Five to eight pieces comprise an average batch. A few one-offs and an occasional run of 100 or more pieces can also occur.

Keeping machines running productively and workflow moving smoothly is essential. Setup time is a major concern. Years ago, the company made setup reduction a primary focus of its long-standing commitment to lean manufacturing. “True lean manufacturing requires a constant focus on improvement in all areas that are preventing us from being productive, such as any activities that keep machines from cutting metal,” Bill Metz, vice president of operations, says.

About three years ago, Mr. Metz and other managers at Richards Industries began to eye machine-monitoring systems as a better way to keep tabs on what the machines were doing, or not doing. They saw the promise of connecting machines to a network that could automatically collect and feed machine data to applications for analysis and reporting.

“We wouldn’t have to suspect there was a problem before taking a closer look, we could spot the problem and take corrective action more quickly,” Bob Linville, manufacturing manager, explains. However, the management team at Richards Industries quickly began looking beyond machine monitoring as the main value of a connected, networked shop environment. Two other broad and long-standing goals were included as essential parts of this initiative. First, managers wanted to automate the order-data management process so there was less reliance on operator input to capture timesheet entries, inspection results and details about machine utilization. Second, managers wanted paperless, networked distribution of part drawings, workpiece and material sheets, tooling lists, inspection sheets, and setup instructions, along with streamlined downloading of CNC part programs.

At the beginning of 2015, Richards Industries officially launched its machine-monitoring initiative and by June had a pilot program of 10 machines connected to a monitoring system for machine-data collection, data visualization on the network and automatic alerting. Another 18 machines are currently in the process of being connected. When completed, this machine-monitoring system will constitute Phase 1 of the long-range plan. Phase 2 will be the implementation of order-data management. Phase 3 will be product-data management and enhanced DNC.

With the 10-machine pilot project in operation for about 10 months now, Mr. Linville confidently says the effort has been a success—with tangible, measurable results that “prove an improvement.” He says that overall equipment effectiveness (OEE), which factors in productivity, performance and quality of output, is at least 20 percent higher than before machine monitoring was in place.

To encourage and help other shops move toward machine monitoring—and more—Mr. Metz and his colleagues have these recommendations and advice, which fall into five topic areas:

1. Have vision and commitment at the top.

2. Use a pilot program to set the course.

3. Reinforce shop culture with good communication.

4. Rally the team around an enthusiastic leader.

5. Get good data, and act on it appropriately.

Commitment at the Top

Richards Industries has been manufacturing specialty valves at its Cincinnati location since 1947. It has a history of company ownership that looked for ways to improve its manufacturing operations, its service to customers and the quality of life for its employees in the workplace. Its embrace of lean manufacturing and setup reduction almost 15 years ago is a prime example of this forward thinking. Concern for workforce relations and well-being is attested by the fact that the company has been voted one of the best places to work in the Cincinnati area, recently receiving top scores in six of the past seven years.

“One reason lean manufacturing made a difference here was the commitment of Gilbert Richards, then-owner of the company, to implementing it in earnest,” Mr. Metz says. The company is now owned by a number of its top managers, including Mr. Metz. They have not forgotten this lesson.

Today’s ownership group is solidly behind the move to machine monitoring. In fact, the impetus to get started can be traced to discussions among this group when machine monitoring first took on its current momentum with the introduction of shopfloor interoperability standards such as MTConnect about eight years ago.

Mr. Metz says that this essential “top management buy-in” has to be more than words. Positive actions are also necessary.

For example, shop owners must be committed to making the monetary investment. This means fully analyzing, reviewing, justifying and funding the cost of a machine-monitoring system. The budget should cover acquiring the system, installing the infrastructure, devoting workforce resources and training users thoroughly. The return on this investment has to be calculated, without losing sight of overall value.

“We figured that the most conservative estimates of productivity gains from machine

monitoring would be about 5 percent. We used this figure to justify the cost of the machine-monitoring system, and it has paid off,” Mr. Metz says. That said, he notes that the return on a monitoring system is not derived from the system itself, but from the actions that help operators and machines become more productive.

Likewise, it is important for top managers, supervisors and leadmen to be involved in

all aspects of planning and implementing a machine-monitoring system. “This is best done with a team approach,” Mr. Linville suggests. For example, early in the process, Richards Industries created a committee that included representatives from management, shop supervisors, leadmen, IT personnel and manufacturing engineers. This key group was heavily involved in the choice of the software provider with which to partner, and it will remain heavily involved through implementation of Phases 2 and 3 of the plan.

Plan Big, Start Small

Perhaps the most important decision Richards Industries made was to think beyond machine monitoring. By determining what other benefits could be derived from the monitoring network, the company realized it could go farther and get there faster with its Phase 2 and Phase 3 concepts in mind at the beginning. For this reason, Richards Industries selected Forcam, a software firm specializing in systems for discreet parts manufacturing that take a unified approach to achieving improvements across all operations, as its supplier for the machine-monitoring system. This decision was made largely on the basis that this supplier offered additional software products and capabilities for providing order-data management and product-data management/DNC.

Based in Germany, where Forcam has had considerable success as a systems integrator for larger companies in the automotive industry there, the software company chose Cincinnati as its U.S. base with the intent to focus on systems for small- and medium-sized manufacturing companies in this market. “Once we had Forcam on board, we could get their system engineers working with us to set objectives, create a timeline and establish criteria for how data was to be collected and used,” Mr. Linville explains.

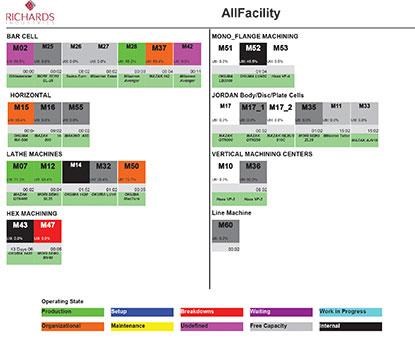

The 10-machine pilot program represents Richards Industries’ initial installation of the Forcam Force Shop Management suite of software tools for machine-data collection, visualization (displays of pie charts, performance bars and trend lines), report generation and issuance of alerts. The first step was conducting a connectivity audit of all machines in the shop, then selecting the 10 with the heaviest usage or most critical operations that could become bottlenecks. The machines selected also represented the variety of adapters or interfaces needed for all of the company’s machines. Getting these connections up and running during the pilot program would greatly facilitate shop-wide network implementation, which commenced in January 2016.

Half of the first 10 CNC machines were equipped with CNCs that were MTConnect-compliant (MTConnect is the machine tool interoperability standard that translates machine tool data into a common, Internet-based language). Forcam and Richards Industries worked together to filter the stream of MTConnect-formatted data so that only selected items for relevant reports were captured. One of the 10 machines required an IBH Link interface for formatting and tagging the data generated by its Siemens control system. Four other legacy machines required installing a Wago data-collection device that is connected to the input/output (I/O) board inside the control unit. These older CNC machines ran software with limited or nonexistent data reporting, necessitating that machine status and other operational events to be collected from the I/O signals.

Mr. Metz also emphasizes that it is critical to have the IT department involved from the very beginning of the process. “The support of Jeff Howard and Beth Mogg of our IT department has been outstanding. Their efforts have been critical to our success, and we will rely are on their involvement until the program is completed,” he says. For its part, the IT department was responsible for having electrical power lines (for backup purposes) and network cables connected to all 10 machines. Network security measures such as “firewalls,” password protection and encryption were also under the IT department’s jurisdiction.

Communicate, Communicate, Communicate

Aware that a machine-monitoring system needed acceptance and commitment on the part of the shopfloor workforce, managers at Richards Industries made good communication a top priority during the planning and installation of the system.

The plans to implement a system were communicated in quarterly update meetings for more than a year, before installation began. Once the decision was made to go ahead, separate meetings with all operators were held with the support of Forcam personnel to review the system and its benefits and capabilities. During implementation, meetings were held with small groups of operators to review the Shop Floor Terminal interface and what was expected of the operators.

As much as possible, decisions were made jointly through these informal committees. For example, unlike most shops with monitoring systems in place, Richards Industries does not have large screens in the production area displaying a dashboard or shop report. The consensus among machine operators was that making reports and dashboards only available on desktop computers or laptops at workstations was more useful and less intrusive.

The emphasis on communication is equally important after a monitoring system is gathering data and rendering reports. Mr. Linville makes a point of using the production data as a basis for his daily discussions with supervisors and machine operators. “I can scan a report such as the Operating State Trends report and spot issues such as long setup times or undefined machine stoppage,” he explains. “I’ll ask about why this or that is happening, but also ask what we can do together to resolve issues and make improvements. We need only five or 10 minutes for this.”

Likewise, weekly “Forcam improvement” meetings are now centered on the reports from the monitoring system. As Mr. Linville points out, “When everyone is starting with the facts, discussions can quickly focus on problem-solving suggestions, agreed action items, maintenance priories and so on.”

What Richards Industries’ experience says about the value of communication can be summed up this way: A shop that has good lines of communication in place must keep them open and active when introducing shopfloor monitoring. There should be no surprises. Implementers need to listen and pay attention to intended users. Likewise, a shop can and should find ways to use the data from a monitoring system to strengthen shopfloor communications.

“Monitoring should always be a cohesive force, not a divisive one. That all hinges on good communication,” Mr. Metz concludes.

Choose a Champion

There is no question that implementing a machine-monitoring system is a team effort on every level, yet Richards Industries points to Bob Luthy, the continuous improvement/safety manager, as the main champion of the shop’s machine-monitoring initiative. As the leader of the company’s ongoing Continuous Improvement Program, Mr. Luthy was in a natural position to take on this role when the pilot program was launched last year.

He served as the key contact person and liaison with Forcam. He is the “go-to guy” for both the shop and the system supplier. He coordinated the effort to match Richards Industries’ machine-monitoring objectives with the data collection and reporting capabilities of the Forcam system. “Mainly, this involved determining what data we wanted on our side and how Forcam could best organize this data and generate the reports that gave us the insights we needed,” Mr. Luthy explains.

He coordinated many of the details of installing the system. For example, he and Mr. Linville scheduled when individual machines could be pulled out of production to hook up the network connections with the least disruption.

Once trained thoroughly by Forcam, Mr. Luthy became chief trainer of system users in the shop. For operators, the training covered familiarity with Forcam’s Shop Floor Terminal interface at each machine. For supervisors and managers, it covered familiarity with Forcam’s Force interface—the suite of reports and performance summaries. As part of this function, Mr. Luthy also acts as chief listener, the person who gathers suggestions and questions (especially from operators) and presents them to the system supplier for a response. He has also helped the management team understand some of the ways to interpret what the monitoring system was showing about shop performance.

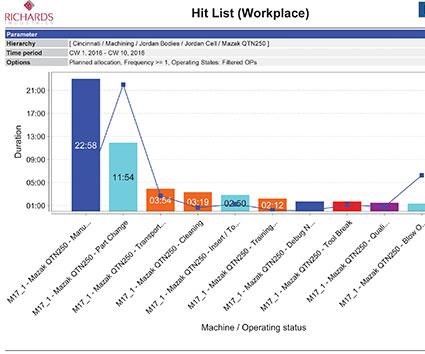

Of course, Mr. Luthy usually leads the review of shop data at the weekly continuous improvement meetings. For example, by going through the previous week’s results, the top 10 causes of nonproductive time can be identified and targeted for improvement during the current week. “This is our hit list,” he explains.

Mr. Linville credits Mr. Luthy with helping the most to change the shop culture at Richards Industries in a smooth and positive way. “We didn’t want machine monitoring to be resisted as spyware, but accepted as a tool that helps everybody,” he says. “Bob [Luthy] kept the move to machine monitoring open and transparent. He led the teamwork that made machine monitoring not only acceptable, but embraceable—for operators as well as leadmen, supervisors and managers at all levels.”

Good Data Used Wisely

Collecting and analyzing data, sharing reports and displaying results are all pointless if they do not lead to improvements and positive actions. Here are some representative examples of how Richards Industries has benefited from machine monitoring.

Setup reduction. After a few weeks of monitoring, it became apparent that the Okuma LU15 lathe was requiring around eight hours a week for setup, which the operator had tagged as “jaw work.” A quick discussion of this issue with the operator revealed that he was routinely reboring hardened chuck jaws to match the diameter of barstock. By acquiring a set of master chuck jaws with soft top jaws in sizes matched to the barstock running on this machine, jaw work has dropped to less than four hours a week.

Less material handling. Encouraged by these results, the shop started looking at the time spent on changing barstock sizes across all of the turning machines. This led to greater attention to grouping orders on the shop schedule by barstock size to reduce change-overs. It takes a little longer to juggle the shop schedule to keep delivery dates on track, but overall time for barstock changes has dropped by about 10 percent in the last three months, Mr. Linville estimates.

“We’ve made [reducing time for] material handling a priority,” Mr. Linville says. “Without machine monitoring to give us a picture of its impact on all 10 machines, we probably wouldn’t have targeted this factor for improvement.” The goal is to cut the 22 hours of material handling per week by 25 percent in the next three months.

More efficient CNC programs. Barry Haenning, the manufacturing programming manager, took a look at the high number of reported stoppages attributed to “program interrupted.” “We found that machine operators were running programs in which the M00 codes for optional stops were still in place,” he reports. These optional stops were originally intended to give operators a chance to do spot checks on tool wear or part size when the program was new or had been edited. Once a program had been proven out, these optional stops were unnecessary, but they were rarely removed because hitting the restart button had become part of the operators’ reflexes, it seemed. A program to review active CNC programs to delete the stops is underway.

Recovering overlooked efficiency. One of the most productive machines in the shop is an Okuma MA500 HMC with a Fastems pallet-changing system. Installed in 2007, this cell was to be the prototype for palletization of other new or retrofit machines. Spindle cut time for this cell, however, was only marginally higher than that of non-palletized machines. What was the problem?

“We discovered that we were sending many of our hot jobs to this machine, and we had gotten out of the habit of setting up this work on a pallet offline. We were expediting the job, but not optimizing use of the pallet changer,” Mr. Linville says. “Now we are staging work for this machine more carefully so the operator has time to keep pallets loaded and queued for production, including those at the end of the shift for lights-out operation.” Spindle cut time is up by 20 percent as a result and steadily moving toward the goal of cutting metal 80 percent of the time during the HMC’s 20 hours of daily operation.

Looking Ahead

According to Mr. Metz, Richards Industries will have completed Phase 1 (all machines networked to the monitoring system) by the middle of 2016. He expects Phase 2 (order-data management) to be in place by the end of the third quarter and Phase 3 (paperless shop communication) by the end of the year.

Looking back, he says that the biggest surprise has been finding that the “real numbers” on shop productivity and machine utilization were not as high as managers thought. “We figured that our machines were cutting metal about 50 percent or so over two shifts. It was more like 40 percent when monitoring first started,” he reports. It is now higher than 55 percent and climbing.

However, looking ahead, getting the three phases completed will be a plus when business picks up. Mr. Metz and Mr. Linville see three reasons for this expectation. One, machine monitoring is helping the shop unlock capacity that has been hidden by activities other than metal cutting. “We can use data to become a leaner operation,” Mr. Metz says.

Two, ramping up production to meet a sales surge will be smoother and more effective. “We can make smarter decisions about allocating shop resources, adding overtime, bringing on new hires or buying equipment,” Mr. Linville says.

Three, keeping the workforce stable and engaged will be easier. Mr. Metz believes that moving to a more thoroughly digital environment, in which decisions are closely linked to data, means less stress and smoother interactions on the shop floor. This will also help the company attract and prepare a younger generation of machine operators and programmers. Mr. Linville points out that a significant number of current employees are approaching retirement age. “We may not be able to replace their skills and experience, but we can create a shop environment where knowledge sharing and collaboration can thrive,” he says.

Change and growth have long been key components of the culture and tradition at Richards Industries. This will continue. Machine monitoring is one more step in this direction, and its benefits are likely to create new reasons for its employees to vote the company one of the best places to work in the city.

Related Content

Give Job Shop Digitalization a Customer Focus

Implementing the integrated digital technologies and automation that enhance the customer's experience should be a priority for job shops and contract manufacturers.

Read MoreLeveraging Data to Drive Manufacturing Innovation

Global manufacturer Fictiv is rapidly expanding its use of data and artificial intelligence to help manufacturers wade through process variables and production strategies. With the release of a new AI platform for material selection, Fictive CEO Dave Evans talks about how the company is leveraging data to unlock creative problem solving for manufacturers.

Read MoreProtecting Your Automation Investments

Shops need to look at their people, processes and technology to get the most of out their automation systems.

Read MoreSwiss-Type Control Uses CNC Data to Improve Efficiency

Advanced controls for Swiss-type CNC lathes uses machine data to prevent tool collisions, saving setup time and scrap costs.

Read MoreRead Next

Setup Reduction Is Central to Lean Manufacturing

This shop cut average setup time nearly in half. Now small batches can move quickly through the production process, making the company more responsive to customer needs than ever before.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More