Adding Part Traceability to CNC Machine Monitoring

Focusing on what makes money puts CNC machine monitoring data in context.

Share

By itself, machine monitoring is not enough to gage manufacturing process performance.

To understand why, consider an analogy from Dr. Shahrukh Irani, a lean manufacturing consultant. He compares the machine shop with a piece of woven fabric. The vertical threads represent the workstations, and the horizontal threads represent the work. Through the lens of the machine monitoring system, the vertical threads are fully visible, stretching from one end of the fabric to the other. However, the horizontal threads are visible only at the intersections, where parts meet machines. The result is an incomplete patchwork of latticed chunks that provides limited insight. “You make money by moving metal through the shop,” Dr. Irani explains. “If you lose traceability of the parts from the moment the cycle finishes on machine one until the next cycle begins on machine two, how can you move the money faster?”

This is not to suggest that equipment utilization and health data are not inherently valuable, but that this value compounds when data is considered in the proper context. For evidence of that, consider the experience of Superior Completion Services (SCS), an oilfield industry manufacturer near Houston. SCS had been collecting CNC data for five years by the time I visited them, and the machine monitoring system played a major role in the transformation I’d come to write about. However, it was not the catalyst of that transformation. The catalyst was the application of many of the same principles that have defined effective manufacturing processes for decades. Only then did the shop’s use of machine monitoring begin to evolve.

The decades-old principles in question form the foundation of Dr. Irani’s approach to lean manufacturing. Pulling from the theory of constraints, the human resources aspects of the Toyota Production System, and various other disciplines, his approach is designed specifically for manufacturers contending with a variety of unique parts produced in low volumes (that is, job shops). Kaizen, 5S, “waste hunts,” and other common lean tools might all have a role to play. However, his focus is mostly on the allegorical horizontal threads — how work flows through the facility.

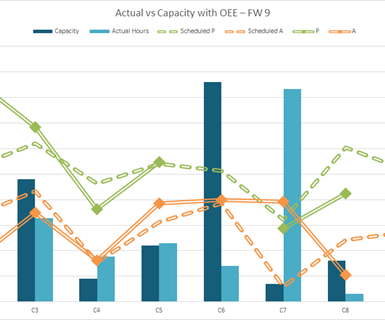

Overlaying overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) metrics from the machine monitoring system on this capacity chart helps Superior Completion Services (SCS) schedule work more effectively.

Specifically, the method involves identifying product families, designing a factory layout to facilitate flow, and production planning and scheduling based on finite capacity constraints. At SCS, this focus on flow drove a complete reorganization of the shop floor. With more than 60,000 unique part numbers, all made to order and often in single-digit quantities, the assembly line ideal is impossible to achieve. However, the new approach helped limit batch processing and work in process, improve throughput, and otherwise approximate single-piece flow as closely as possible.

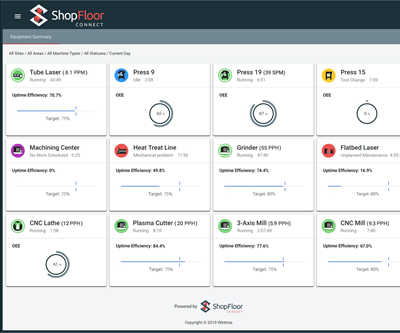

At this point, the focus returned again to the vertical threads. Reorganizing workflows and reconsidering priorities and goals opened opportunities to use the machine monitoring data in new ways. The essential role of the software itself remains the same: to output equipment performance data in an easy-to-understand, customizable interface. What’s changed is the extent to which that data is massaged and crunched to arrive at new insights that aren’t necessarily obvious from the dashboard displays. For example, the shop uses metrics associated with overall equipment effectiveness (OEE), a common gage of machine tool performance, to understand its capacity and how well it is being used.

I already told that story. The point is that the OEE metrics never would have been used in this way if the team had not recognized the value of bringing the entirety of the allegorical “fabric” of production into view. Making the most of the system required understanding how its output fit into the broader context: that is, a more data-driven, disciplined approach to workflow tailored specifically to SCS, but rooted in core lean manufacturing principles.

Related Content

Can Connecting ERP to Machine Tool Monitoring Address the Workforce Challenge?

It can if RFID tags are added. Here is how this startup sees a local Internet of Things aiding CNC machine shops.

Read MoreHow this Job Shop Grew Capacity Without Expanding Footprint

This shop relies on digital solutions to grow their manufacturing business. With this approach, W.A. Pfeiffer has achieved seamless end-to-end connectivity, shorter lead times and increased throughput.

Read MoreProcess Control — Leveraging Machine Shop Connectivity in Real Time

Renishaw Central, the company’s new end-to-end process control software, offers a new methodology for producing families of parts through actionable data.

Read More5 Stages of a Closed-Loop CNC Machining Cell

Controlling variability in a closed-loop manufacturing process requires inspection data collected before, during and immediately after machining — and a means to act on that data in real time. Here’s one system that accomplishes this.

Read MoreRead Next

3 Principles for Growing with Machine Monitoring Data

Following a few basic principles can help shops get a return on their machine monitoring systems without losing faith first.

Read MoreMachine Monitoring Provides an Objective Lens

Automatic, real-time shopfloor data collection tempers the bias that blinds manufacturers to the real reasons for downtime.

Read MoreManufacturing Scheduling System Keeps Shopfloor Priorities Straight

Focusing on the now rather than adhering to a plan improves throughput, allows for variation and lays a strong foundation for predictive analysis.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)