Cutting Edge Control Speeds Cross-Hole Deburring

As opposed to springs or other mechanical means of driving tool inserts into hole intersections, leveraging pneumatic or hydraulic pressure provides a means of process control beyond feed and speed adjustments.

Share

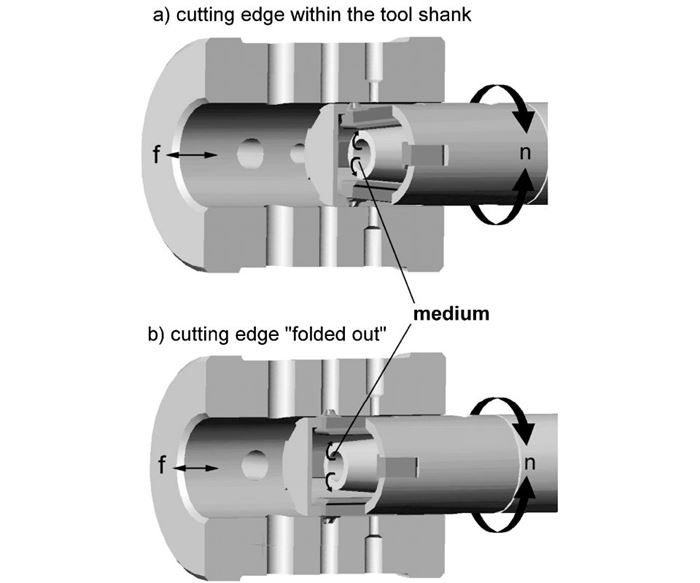

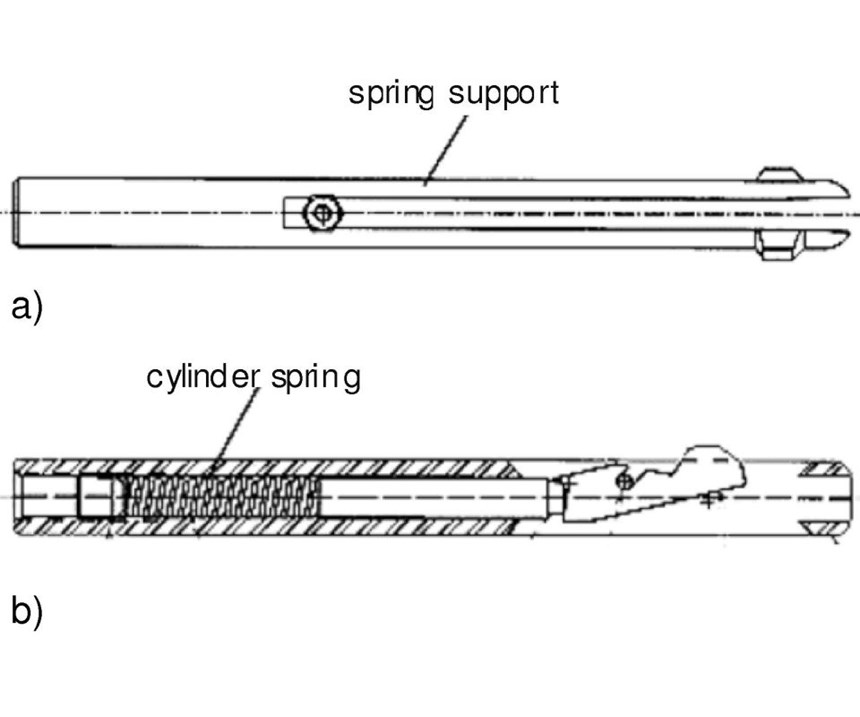

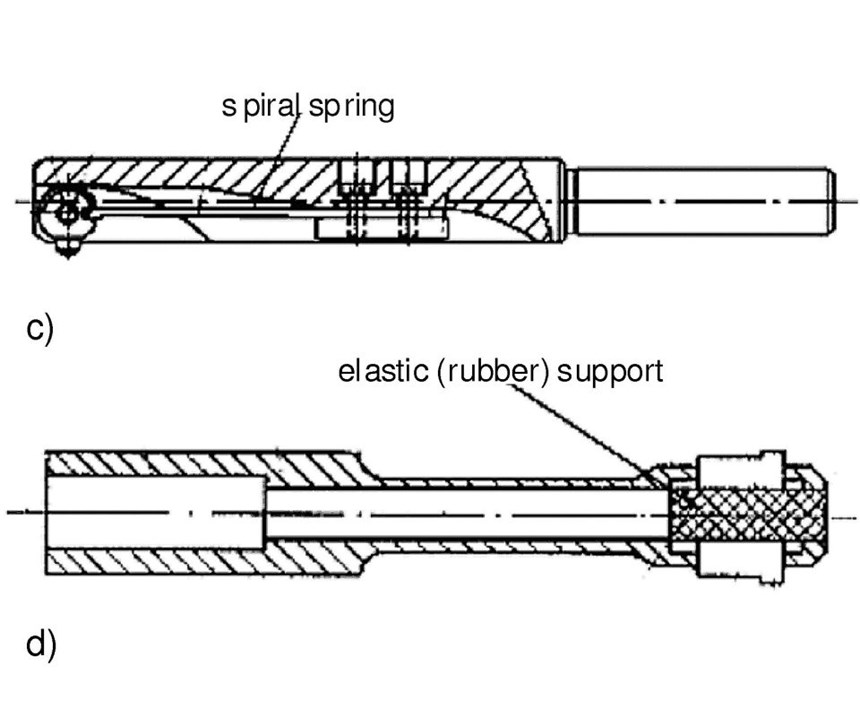

Consistency and speed can be difficult to achieve in cross-hole deburring, even when the operation is performed on a CNC machine tool. One common limitation is the cutting tool. Rather than static cutting edges, tools designed specifically for cross-hole deburring tend to employ inserts that spring outward from the shank into the space created by the intersecting bore. Limited to only feed and speed rate adjustments, even the most skilled machinist using proper tool selection might struggle to complete the operation as efficiently as possible. However, testing shows that leveraging adjustable air or fluid pressure to drive inserts into the cross hole rather than springs or spring-like components can significantly increase capability to compensate for process variability and to machine more aggressively and uniformly than would be possible otherwise.

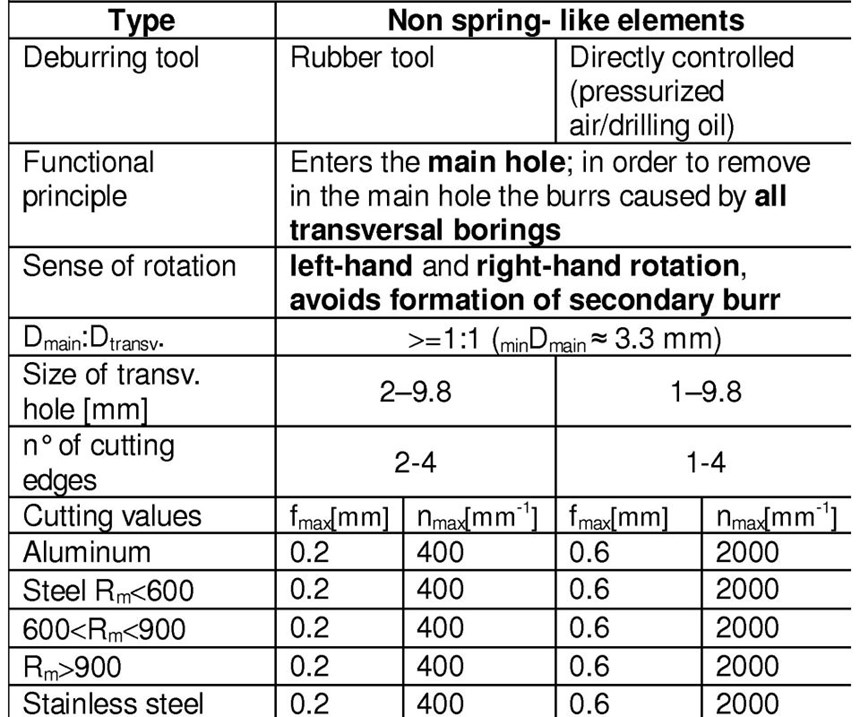

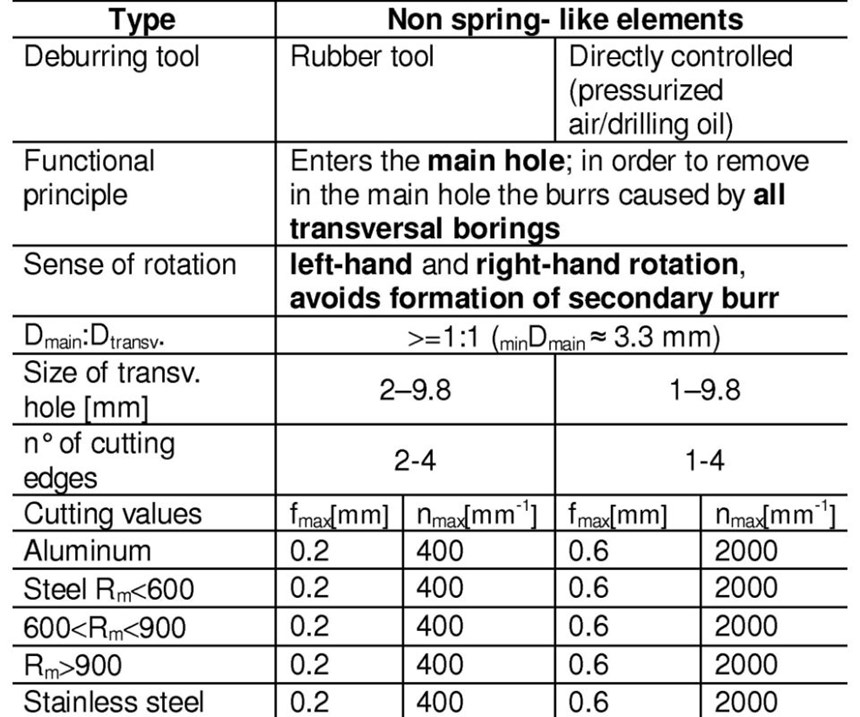

In Germany, the Dr. Beier-Entragattechnik company conducted tests pitting one of its pneumatic tools against four other configurations common in automotive and general job shop deburring applications that involve cross holes and non-flat bore exits. Although each of the latter four tools exhibited its own advantages and disadvantages, testing revealed that their reliance on mechanical actuation severely limits control over the speed, force and timing of the cutting edge’s projection from the tool body.

As opposed to hydraulic or pneumatic pressure, the pre-tension of a spring or the elasticity of a rubber-insert actuator cannot be adjusted during the deburring operation, researchers explain. As a result, the range of possible parameters for a given application is dependent on friction and the inertia of the spring mechanism. As for quality, mechanically actuated inserts do not sit loosely in a slot on the side of the tool shank until needed, as is the case with the company’s pneumatic and hydraulic models. Rather, they are under constant tension, and they exert constant pressure on the bore interior as they feed inward toward the intersection. As a result, pushing such a tool into the bore too aggressively, or rotating it too quickly during the feed, can potentially mar a critical surface.

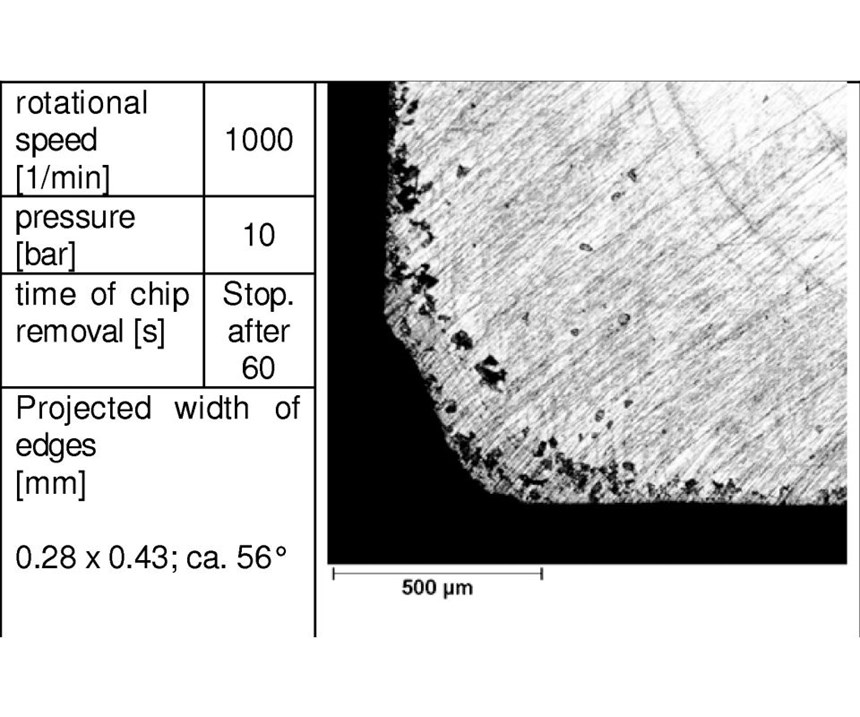

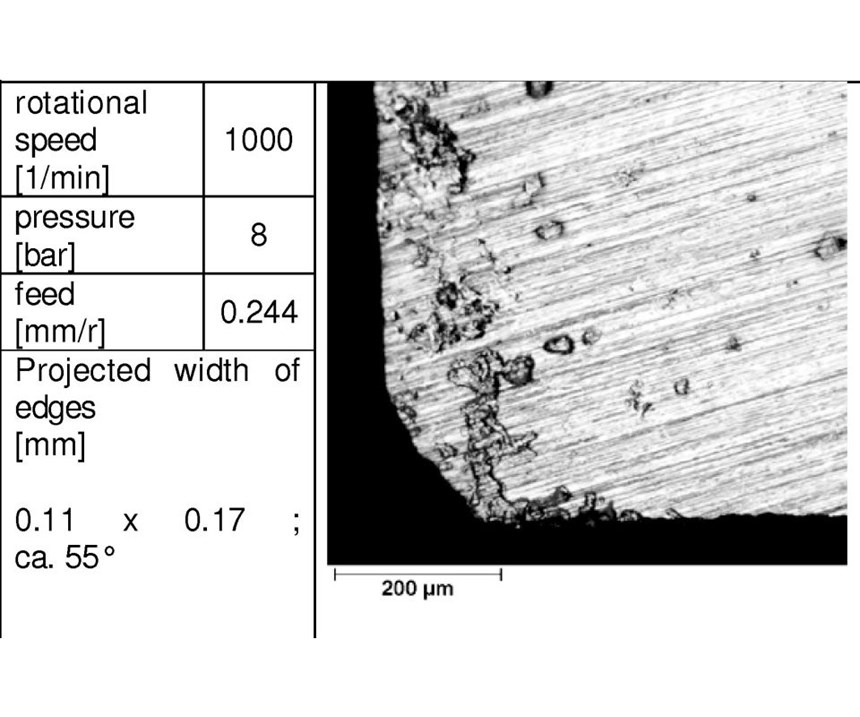

Adding to the challenge are ever-increasing standards for precision. According to the researchers, cross-hole deburring and, particularly, bore-exit applications increasingly require not just burr-free surfaces, but precisely defined radii and/or chamfers that measure in the hundredths of an inch in some cases. Even with extensive knowledge of how burrs form in a particular workpiece, the process can be unpredictable. For instance, the precise location and orientation of the elliptical surfaces where burrs form varies according to the tolerances of the intersecting holes, thus precluding the possibility of assigning a geometrical base plane. Burrs also tend to vary in size and shape. Progressive tool wear during initial drilling also contributes to process variation, as do chips that tend to accumulate when a drill breaks into an existing hole. With a means of controlling the interaction of tool and work beyond speed and feed adjustments, users can dynamically compensate for changing burr dimensions and other variables during the machining process.

The company’s hydraulic and pneumatic tools differ from most mechanically actuated models not only in design, but also in operation. Rather than entering the cross hole, they enter the main bore, where the burrs created by cross-hole drilling are located. They also reverse direction during the process, spinning clockwise on the way into the main bore before stopping briefly and switching to counterclockwise rotation before backing out again. By comparison, mechanically actuated tools that rotate in the same direction throughout the process are more prone to creating secondary burrs. Also, entering through a cross hole limits cleanup to a single intersection. In contrast, approaching through the main bore enables the tool to remove all burrs on the way in, as well as those formed by any number of intersecting holes. (Some mechanically actuated tools—including one tested model that uses rubber elastic—do enter the main bore and reverse rotational direction. However, the researchers point out that control of these tools is still limited to speed and feed-rate adjustments.)

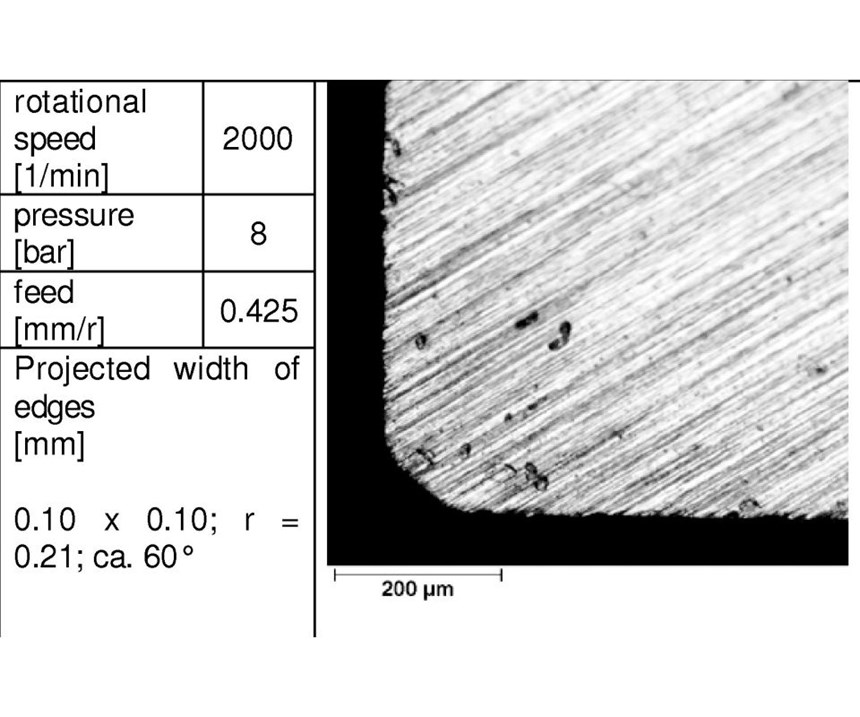

Controlling the protrusion of the cutting edges requires particular attention to the interaction of feed rates with air or fluid pressure. For instance, testing shows that driving cutting edges farther from the shank can be accomplished by increasing pressure at constant feed, reducing feed at constant pressure or adjusting both parameters. A less-pronounced cutting edge requires reducing pressure at constant feed, increasing feed at constant pressure or varying both. Feed rates also dictate the shape of the deburred edges, with more aggressive settings producing smaller chamfers and less aggressive settings producing larger chamfers (without feed, the angle of the chamfer or radius depends on the geometry of the cutting edge).

All in all, the testing demonstrated that deburring tools leveraging hydraulic or pneumatic cutting-edge control enable higher rotational speeds and feeds without significant negative effects on deburred surfaces. What’s more, varying pressure, feed and rotational speed enables users to change deburring quality on the fly, even setting pressure (and therefore, force) to zero if need be to avoid damaging high-quality surfaces.

Related Content

Ingersoll Rand Offers Two New Belt Sanders for Smooth Finishes

Ingersoll Rand’s 360-313 and 360-418 Pneumatic Belt Sanders work effectively on metal, plastic, fiberglass, wood and other materials.

Read MoreMastercam Software Improves Programming Flexibility

IMTS 2024: Mastercam introduces Mastercam 2025, with features including Mastercam Deburr for automated edge finishing, finish passes, mill-turn support for Y-axis turning and automatic license update notifications.

Read MoreTrumpf Deburring Tool Provides Repeatable Accuracy

The TruTool TKA 1500 edge milling tool is now available with a new cutting mount and guide fence for increased applications and safety.

Read MoreHow to Accelerate Robotic Deburring & Automated Material Removal

Pairing automation with air-driven motors that push cutting tool speeds up to 65,000 RPM with no duty cycle can dramatically improve throughput and improve finishing.

Read MoreRead Next

Registration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More