What’s Your Place in the Future of Making?

Autodesk’s annual user conference shed light on a machine shop’s place in an era of democratized, automated product development and merged design and manufacturing workflows.

Share

“Machinists were created because engineers need heroes.”

According to the recollection of past attendees and presenters, these words were emblazoned across T-shirts popular among the machining crowd at Autodesk’s annual user conference, Autodesk University (AU), a few years ago. The shirt was fitting for the occasion, with the company fresh off a number of investments evidencing its increasing focus on CAM software in addition to its traditional design and engineering offerings.

That’s not to suggest the engineering side wasn’t well-represented. These personnel reportedly preferred a different T-shirt, this one with a new take on the iconic phrase from the Declaration of Independence: “All men are created equal, then a few become engineers.” Presenting a humorous play on a history of tension between the disciplines, the juxtaposition was no doubt also intended to emphasize the company’s increasing emphasis on the intersection between the two.

Fast-forward to AU 2017, and this intersection is ceasing to exist, at least based on the testimony of Autodesk personnel and guest speakers at the Palazzo hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, November 13-16. That is, engineering and production must be considered as parts of the same whole. “The industry is changing. There’s a lot more mutual respect,” said Al Whatmough, CAM product manager, during one presentation. “Supercomputer engineers are working next to guys who’ve been running manual machines in their garages for years.”

In Autodesk’s view, bringing design and manufacturing together isn’t just desirable, but essential to survival in a future of more democratized product development. Finding a place in this fast-encroaching future is particularly important for discrete parts manufacturers. After all, they’re the heroes on the front lines, those in the business of literally making dreams tangible. Without an understanding of the broader context in which they operate, it may be difficult to understand what’s necessary to become viable members of increasingly compressed supply chains. That is, to understand how leveraging technology available now can help take the first steps toward integrating design and manufacturing workflows.

The New Product Development Paradigm

AU proved an ideal venue for putting the future of discrete parts manufacturing in broad context. Indeed, Mr. Whatmough estimated the proportion of the more than 10,000 attendees primarily interested in CAM software at no more than a few hundred. The rest consisted of engineers, entrepreneurs, architects and more, all users of Autodesk products for industries ranging from construction to medicine to media and entertainment. The common thread among these users is a need to create—hence the conference theme, “The Future of Making Things.”

Another common thread among many of these disparate users is Autodesk’s open-architecture, cloud-based data-sharing platform, Forge, which forms the foundation of the company’s various software offerings. Based on the presentations and demonstrations at AU, promoting this application commercially—pushing it as a foundation upon which companies in virtually any industry and at any node in the supply chain can build workflows, share data and communicate and collaborate throughout a product’s production cycle—is a chief priority for Autodesk.

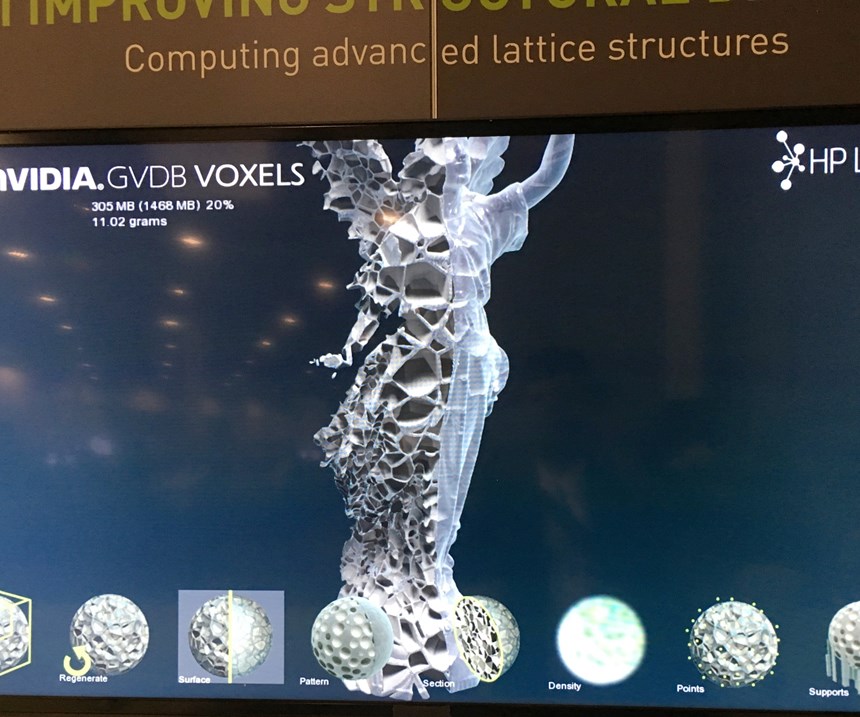

Indeed, AU 2017 revealed the company’s vision for the future to be as broad as its product offering. Demonstrations from various partners showed how augmented and virtual reality enable all the experimentation required for real-world problem-solving without real-world constraints, whether in planning the motion of a robot arm or the layout of a factory floor, apartment or neighborhood (and in one case, a city on Mars). Cloud-linked computers processing in parallel and graphical processing units that instantaneously render 3D models and photorealistic images are accelerating design iteration and opening the door to making the most of new technologies. Some designs showcased at AU featured complex lattice structures, producible only via the latest additive manufacturing technologies and based on concepts initially conceived not by a human being, but by a computer. This generative design technology enables starting projects with a broad range of viable geometric possibilities that can spur ideas and accelerate the journey toward the final iteration.

All in all, AU conveyed the message that the rules of the game remain unchanged in one fundamental sense. That is, the faster a developer can iterate a new product design, the more successful it tends to be. The difference now, and increasingly in the future, is that automation is compressing that cycle even as it enables more people in more places to make their dreams a reality.

Data at the Center

What does this new product development paradigm mean for producers of machined parts? Trends toward greater specialization of services and greater modularity, customization and geometric complexity in product lines—the same trends at work in construction, entertainment and so forth—will continue, as will the trend toward demand for more data on part and process alike. Amid what’s been referred to as the “uberization of manufacturing,” there’s no room for confusion about exactly what’s happening on the shop floor.

The need for comprehensive, real-time operational visibility has led Autodesk to develop Fusion Production. This is a workflow-management system based on the Forge platform that offers production planning, job tracking and machine monitoring. Said to be particularly useful for smaller contract manufacturers, the tool differs from traditional enterprise or materials resource planning systems in that it is cloud-based. This reportedly enables leveraging data not just for internal purposes, but also making it available in real time, from any internet-connected device, at any node along the product development cycle. Among other capabilities, this is said to enable users to view and edit job schedules from anywhere; to easily integrate CAD and CAM part data; and to send part data directly from CAD/CAM software as digital work instructions; all with the same tool.

The company expects to share more detail on availability and pricing for Fusion Production in early 2018. Meanwhile, technology available now can reportedly help plug in to a more more seamless supply chain with increasingly less room for paper prints, less time to render models and simulations, and less patience for transferring design files from format to format. The idea is to be defined by the data —the machining parameters, quality information, design specifications and other intellectual property that makes a company different—rather than the software tools used to work with that data. This facilitates the new approach, one in which design and manufacturing can be thought of not as separate disciplines, but as part of a single, continuous process.

The extension of AnyCAD technology to the Fusion 360 integrated CAD/CAM offering is the company’s latest step in this direction. Since 2015, AnyCAD has been enabling users of Autodesk Inventor software to import designs in virtually any other format (including PTC Creo, Solidworks, NX and more) without the need for translation. They’ve also enjoyed full associativity; that is, design updates made in one system can be reflected automatically in the other. Now, users of Fusion 360 can take advantage of these same capabilities. They can also leverage Inventor, or even software beyond Autodesk’s offerings, as a value-add where certain capabilities or tools are a better fit for the task at hand. In Autodesk’s view, continued expansion of such capability is essential to helping more manufacturers put data, not specific CAD/CAM tools, at the center of their operations.

What does “data at the center” look like in practice? Kalitta Motorsports, a drag-racing organization, offered perhaps the most striking AU example of a machining business with data at the center and a merged design/manufacturing workflow. Granted, in this case, all design and manufacturing already occurs under one roof. However, that’s precisely what makes Kalitta such a good example. It’s quite easy to imagine how the very same technology employed by Kalitta could be applied by virtually any kind of machining business involved in development and production cycles spread across multiple, disparate locations and suppliers. Learn more here.

Related Content

Generating a Digital Twin in the CNC

New control technology captures critical data about a machining process and uses it to create a 3D graphical representation of the finished workpiece. This new type of digital twin helps relate machining results to machine performance, leading to better decisions on the shop floor.

Read More5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreHow this Job Shop Grew Capacity Without Expanding Footprint

This shop relies on digital solutions to grow their manufacturing business. With this approach, W.A. Pfeiffer has achieved seamless end-to-end connectivity, shorter lead times and increased throughput.

Read MoreERP Provides Smooth Pathway to Data Security

With the CMMC data security standards looming, machine shops serving the defense industry can turn to ERP to keep business moving.

Read MoreRead Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More