What It Takes for Oilfield Success

Hunt and Hunt’s president says adopting turn/mill machines was one of the most challenging endeavors his 55-year-old shop ever undertook. He also says it’s the best thing the shop could have done to become more efficient at contract work.

Share

A two-lane road separates Hunt and Hunt’s two manufacturing facilities in Houston, Texas. Such a physical separation seems fitting, because the newer building, constructed in 2005, represents a departure from how the shop once approached parts production for its oil and gas customers.

Michael Bowman, Hunt and Hunt’s president, says sudden growth six years ago caused him to rethink the shop’s strategy for the contract machining portion of his business. In 2004, demand for machined oilfield components soared. As a result, the shop expanded its workforce from 40 to 130 employees in short order in an effort to meet demand and stave off its competitors. Despite the additional help, the shop still struggled to keep pace.

It was clear that Hunt and Hunt needed to become more efficient at machining parts. Traditionally, it had produced parts in good-sized batches that were transported from one machine to another until completed. This led to large amounts of work in process and significant part travel throughout the shop.

Adding the second building was more than just a signal to customers that the shop was making strides to grow so it could better support their demand. It offered a clean slate that enabled Mr. Bowman to implement a fundamentally new approach to parts production. Rather than installing the types of CNC mills and lathes the shop and its employees were comfortable using, Mr. Bowman began populating the fresh floor space with advanced turn/mill machines even though the shop lacked experience with such multifunctional equipment.

Mr. Bowman says this was his company’s most challenging endeavor. He’s quick to point out, though, that it was also the best decision he could have made to help his shop.

Now with five turn/mill machines and a good deal of banked experience optimizing multitasking processes, Mr. Bowman believes Hunt and Hunt has a competitive advantage over other shops still battling it out with separate lathes and mills. Complex work flows through the new building in a more streamlined manner and work in process is kept in check.

However, writing a check for one of these advanced machines is the easy part (sort of), as Mr. Bowman pointed out during a recent visit to his Texas shop. Getting the most out of this equipment takes a complete dedication to understanding it. Shops that don’t put forth a concerted effort to multitasking success aren’t likely to achieve this machining platform’s full potential, he believes.

The Evolution of an Oilfield Shop

Hunt and Hunt’s operations currently occupy more than 110,000 square feet of manufacturing floor space. However, it began where so many other U.S. shops have: in a garage. David and Julianne Hunt started their shop in 1954 using a jeweler’s lathe to produce electrical components for customers. Mr. Bowman, their son-in-law, joined the company at its current Houston location in 1980. A few years later, the shop purchased its first CNC turning center—a used Mori Seiki SL6—because it recognized other shops were making the move to CNC.

Hunt and Hunt continued adding CNC equipment over the next few years as it concentrated on contract work largely for oil and gas customers. In 1988, Mr. Bowman convinced the Hunts to delve into production work, an initiative sparked by a good customer hoping the shop would manufacture perforating guns used by oil well service companies. (Perforating guns generate a controlled explosion down a well to enable extraction of oil from a reservoir.) Not surprisingly, this venture led the company to integrate an unfamiliar machining technology—rotary laser cutting—to produce one of the perforating gun’s two main components.

Perforating guns consist primarily of a charge carrier and an outer perforating tube. A charge carrier is a thin-walled tube with multiple holes to accommodate explosive charges. At first, the shop used an outside company to stamp holes in flat sheets that were then rolled and welded to form charge carrier segments. However, this process lacked repeatability and accuracy.

Although lasers for tubular workpieces were available about that time, the shop felt they were prohibitively costly. So Hunt and Hunt decided to build its own rotary laser cutting machine, installing a resonator, beam delivery system, laser head and controller to the base of a 1942 Milwaukee mill. The shop has since created seven such laser-cutting machines, refining its design with each iteration. The latest models use compact 2,000-watt Rofin resonators that can cut 30-foot-long tubes as thick as 5/16 inch without a burr.

The charge carrier installs inside a thicker perforating tube. Those perforating tubes have a number of counterbores machined into their outer surface at key positions along their length. These counter bores essentially weaken the tube walls to properly direct the controlled explosions. Large CNC lathes are used to machine seal bores to ±0.001 inch on either end of the tube in addition to stub Acme threads and keyways. Mills are used to machine the counterbores down the length of the tube. Hunt and Hunt, currently the world’s largest producer of perforating guns, makes 17 different gun sizes up to 7 inches in diameter. (See the sidebar below to learn about the automated production cell recently installed to machine perforating gun tubes.)

The shop continued to add CNC lathes and machining centers over the years for both its contract work and perforating gun business. That changed in 2005, when the shop built its second facility and made the tough decision to revisit how it approached contract work by integrating turn/mill machines.

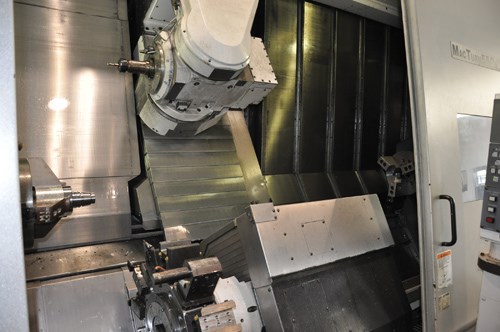

Hunt and Hunt’s first turn/mill was a MacTurn550-W nine-axis machine from Okuma that provided 88-inches between centers and a five-inch through-spindle hole. This machine offered main and sub spindles, a B-axis head and a lower turret.

The adaptor for down-hole tubes chucked in the MacTurn shown on the following page is a prime candidate for the turn/mill. The adaptor, which has been produced on this machine for a number of years, has API threads on one end and stub-Acme threads on the other end. The MacTurn completes the stub-Acme side on its main spindle and then transfers the part to the sub-spindle to allow its lower turret to complete the API side. While this secondary machining occurs, another adaptor is loaded into the main spindle to allow the B-axis head to begin its work again. Mr. Bowman says this part is ideal for the machine because it is complicated and production numbers are fairly high. By reducing the number of machines required along with associated setup and tear down time, the part can be completed in one-third of the time that was previously needed for separate lathes and mills.

The shop’s second turn/mill was an Okuma Multus-B400 six-axis machine with a workpiece capacity of almost 28 inches in diameter by 61 inches long. Although this machine doesn’t offer a subspindle, its B-axis rotation still enables it to perform a variety of operations. Its third and fourth turn/mills were NT 4300 nine-axis machines from DMG/Mori Seiki. Like the others, these machines offer the rigidity to machine tough materials such as Inconel and stainless steel for oil and gas applications. The part shown on page 69 may not look too challenging to create, but it is said to be the second most difficult part the shop has produced. This is largely because of its material (it’s Inconel) and the numerous angled features.

Hunt and Hunt is in the early stages of taking its turn/mill capabilities to a new level. The shop’s fifth turn/mill, an NT 6600 from DMG/Mori Seiki, will be its largest. Delivered in June, the NT 6600 will be able to turn parts as large as 40 inches in diameter and as heavy as 40,000 pounds. In addition, the machine offers a 10-inch through-hole capacity enabling it to completely machine 10-inch-diameter tubular components as long as 32 feet. Mr. Bowman believes the machine will allow the shop to pursue work outside of the oil industry, including components such as large impellers, valves and gears.

Turn/Mill Considerations

In general, Mr. Bowman prefers turn/mill machines that offer a subspindle and lower turret, rather than those that provide only a B-axis head. That way, it’s possible to maximize the number of operations that can be performed on one machine. However, he’s not opposed to using just a machine’s B-axis and main spindle to turn parts for certain applications.

Hunt and Hunt uses off-the-shelf cutting tools when possible. However, it also develops its own form tools as well as custom tools to perform operations such as gundrilling, boring and honing on its turn/mills. The shop uses Solidworks when designing its tools. The goal is to limit tool overhang to minimize vibration during cutting operations while providing sufficient clearance around the part. Visualization of the part and tool interacting in Solidworks simplifies the design process. For machine programming, Hunt and Hunt uses both Esprit from DP Technology and GibbsCAM.

In the five years since adopting its turn/mill mindset for contract work, Mr. Bowman and the folks at Hunt and Hunt have learned a great deal about how best to integrate these complex machines. While turn/mill machines offer a tremendous amount of upside, Mr. Bowman says shops that have no experience with these machines would be well-served to consider the following points if they are considering adding turn/mills.

Know that there will be a learning curve. It will take some time to learn how to use these machines effectively. That’s because you have to rethink everything about how you produce the part, including programming, prove-outs and so on. A bit of patience is required.

Dedicate yourself to this machining platform. There’s no point purchasing a turn/mill machine if your shop isn’t going to go all-out to become proficient at using it. Your best bet is to dedicate your top programmer to mastering the machine. Do the same with your best machine operator.

Don’t oversell the machine before you figure it out. Shops must have some restraint when it comes to taking on a complex job before they really know the ins and outs of their turn/mill. Otherwise, they risk frustration and possibly customer dissatisfaction. A tricky component on display in Hunt and Hunt’s foyer is a good example. It’s a fluid sampling device that the shop initially passed on because it didn’t have the turn/mill process nailed. They’ve since taken on the job and have had great success with it.

“Train” your customers on the machine’s capabilities. It pays to teach your customers a bit about what turn/mills are best at doing. Given the requisite time needed to develop a program and machine that first good part, some level of production is important to absorb some of the process engineering costs.

Don’t be afraid to tweak the process. Shops should experiment with process changes once they’ve figured out how to run a job. Don’t be shy about adjusting speeds and feeds or using different inserts or coolant pressures. In fact, if the production numbers are sufficiently high, don’t be overly worried about scrapping a part as you learn how best to machine it. In many cases, the savings gained through process improvements can outweigh minimal scrap losses.

Try new cutting tools. If a cutting tool representative offers a tool to try, consider giving it a shot. Then, accurately record the machining results and provide as much feedback to the rep as you can so he or she can work with you to develop an optimized process.

Consider training. When Hunt and Hunt purchases a new turn/mill, it immediately begins training its best conventional machine operator on one of its existing turn/mills. That way, the trainee can shadow an experienced turn/mill operator for a period of time so he or she can assume control of the existing machine when the trainer is assigned to the new one. Shops should also take advantage of the training courses the machine tool builders offer.

Related Content

Ballbar Testing Benefits Low-Volume Manufacturing

Thanks to ballbar testing with a Renishaw QC20-W, the Autodesk Technology Centers now have more confidence in their machine tools.

Read MoreInside a CNC-Machined Gothic Monastery in Wyoming

An inside look into the Carmelite Monks of Wyoming, who are combining centuries-old Gothic architectural principles with modern CNC machining to build a monastery in the mountains of Wyoming.

Read MoreHow to Successfully Adopt Five-Axis Machining

While there are many changes to adopt when moving to five-axis, they all compliment the overall goal of better parts through less operations.

Read More6 Machine Shop Essentials to Stay Competitive

If you want to streamline production and be competitive in the industry, you will need far more than a standard three-axis CNC mill or two-axis CNC lathe and a few measuring tools.

Read MoreRead Next

Setting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More