What Is The Right Way To Become An Aerospace Shop?

This Atlanta shop succeeded at becoming an aircraft-industry parts supplier. The lessons of its success have a lot to do with commitment and enthusiasm.

Share

The very first machining center for most job shops is a small, basic, low-cost vertical. But that’s not the way it was at GTI, a family-owned shop near Atlanta.

The very first machining center for this shop was a sophisticated five-axis model from DMG.

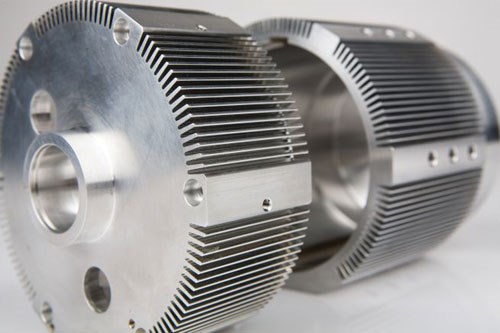

Before that, the only CNC machine in this shop was a wire EDM. Mike Galinac, GTI vice president, says the shop bought the machining center with the belief that it could expand and diversify into complex aircraft parts. What he recognized then—but perhaps failed to fully appreciate—was the fact that the shop had no aerospace contacts, no certifications, no experience in this industry and no experience with a machining center, let alone a five-axis machine.

Then there was the shop’s location. Los Angeles, Seattle, St. Louis—these are active locations for aerospace manufacturing. Atlanta is not.

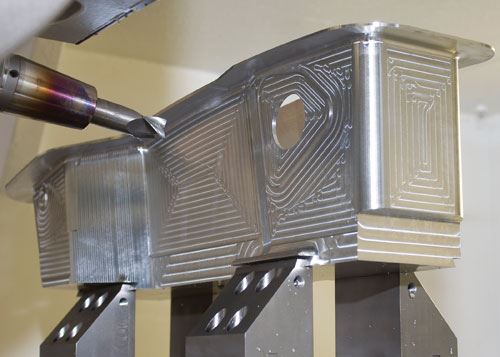

Yet this shop in Powder Springs, Georgia has succeeded enough that it has now replaced that original five-axis machining center with three newer DMG machines, all of which it keeps fed with aircraft-related work. Two of these machining centers are five-axis, and one of them is a model HSC 105V “Linear” machine that features fast-accelerating linear motors in place of ballscrews.

Getting to this point was not easy. In the beginning, and even after the beginning, Mr. Galinac would sometimes look at the five-axis machine sitting idle in the shop and wonder whether buying it had been a mistake. Costs could be even higher when the machine was not idle. Because the complexity of five-axis machining, there was plenty of opportunity for the shop to under-bid jobs.

But the shop hung on. It gained experience. Mr. Galinac was enthusiastic about aerospace machining, and sometimes, that enthusiasm was all there was. Over time, however, some of the jobs turned into customers. Now, given the number of aircraft-related repeat customers, Mr. Galinac can look around and realize that the shop that his father founded has now become an aerospace machine shop.

The Beginning

The shop was founded on a standard product. Michael’s father, Nick Galinac, developed an efficient manufacturing process for gage-related tooling used in the production of camshafts, crankshafts and bearings. The shop continues to make these gage parts with its wire EDM machine and some manual equipment. However, partly because of the travails of the automotive industry and partly because of the rise of the shop’s aerospace work, this standard product now accounts for only about 20 percent of GTI’s business.

When Michael Galinac joined the business, he followed what interested him. He was fascinated by aircraft and the exotic shapes of their machined parts. He was also fascinated by the five-axis machines he saw at trade shows he attended as a boy alongside his father. The look and capabilities of the DMG machines in particular left an impression on him—he never forgot this brand.

When he and his family decided to expand the business, buying a five-axis machine was the step they chose to take together. They soon discovered that owning such a machine and profiting from it are two different things. There were many lessons to learn, and the Galinacs set about learning them, one lesson at a time.

Software Search

One of the most important of these lessons has involved the shop’s search for the best way (the best way for this shop, at least) to program these machining centers. Mr. Galinac says it is easy to underestimate the value and importance of finding a CAM system that makes it practical to take full advantage of the capabilities of the machine.

He began with a less-expensive CAM system that was capable of five-axis programming. The sometimes-questionable accuracy of tool paths involving complex, coordinated motion of linear and rotary axes was one problem with this system. With effort, this limitation could be finessed. But even more significant was the fact that sophisticated CAD capability was missing from the system. The shop struggled with creating, modifying and repairing models.

So the shop went next to a high-end CAD system, implementing the CAD platform and its machining-related modules. However, this system ultimately proved to be too expensive for what it could do for such a small shop, says Mr. Galinac. He says it was also too CAD-focused—practically the opposite problem from the previous system. He wanted a system that emphasized CAM as much as CAD, a system in which advanced modeling was obedient to an equally advanced system for producing tool paths.

He says he finally found this in Topsolid software—with which he has become proficient through the involved support of his local vendor, Clear Cut Solutions. The Topsolid system has powerful design capabilities, he says, but it also stops him from specifying features that he can’t realistically produce on his own machines. In addition, it has proven postprocessors for his machines—a consideration he has learned to appreciate. Any five-axis machining center is a complex machine with a unique axis configuration that makes it at least somewhat distinctive from other machines. Before committing to this latest CAM system, he was careful to determine that the software company already had postprocessors in the field for the machines in his shop.

Getting Customers

Starting out, most of the aircraft-related machining business for GTI came as result of Mfg.com. On Mfg, GTI’s five-axis capabilities distinguish it from many other job shops using this service.

Mr. Galinac says his own particular approach to using this online marketplace sometimes might have made getting work more difficult. He looks for relationships instead of work, and this influences the sorts of jobs he bids on and pursues through Mfg. However, the day came when the shop won a job that has led to various other

relationships.

An aerospace-related customer found GTI on Mfg, and determined from the shop’s profile that it possessed the right five-axis travels to efficiently machine a set of particularly complex parts. GTI won the job—with the requirement that the shop must obtain ISO certification and its own CMM. That was a turning point.

Once GTI had these things, prospects on Mfg.com began to recognize the shop as a supplier with not only five-axis capability, but also a five-axis track record, sophisticated inspection capability and a quality system that validates the inspection. Just one example of a customer that has resulted from this presence is a developer of a type of aircraft doors—a product line that has enough commitments that it seems likely to keep moving forward despite the current economic uncertainty.

Mr. Galinac says customers see something particularly important in the shop’s ISO certification. He fully appreciated the value only after the shop obtained it. It’s more than a piece of paper, he says. Defining and documenting the shop’s procedures, and the means by which the shop realizes all of its capabilities, results in a process that is more disciplined, repeatable and verifiable—and ultimately more productive. A shop cannot consistently reach its potential until it takes the time to examine every step that determines how that potential is reached. Certification forces this examination.

AS 9100 certification for the aerospace industry will come next, Mr. Galinac says. He wishes he had both the inspection capability and the certification much earlier in the shop’s development. But does this mean the shop should have made these investments first, before the five-axis machine?

Maybe, he says. Maybe not.

Just Get Started

Determining whether the shop should have invested in inspection and certification early on leads to a chicken-and-egg problem. Funds are finite. To make these investments, the shop would have economized by buying a less expensive, less sophisticated machining center.

Mr. Galinac notes that this certainly would have given him a machine that was easier to program and easier to learn to apply. However, it also would have given him the same kind of machine that other shops have—too many other shops. This would have taken away a difference that made his shop distinct.

Imagining what would have been the “smarter” choice is probably fruitless, he thinks. The very smartest choice from the very beginning would have seemed to have been to stick with the established gaging product and try to build on that. Instead, GTI’s owners decided to expand the shop into something new.

To get there, GTI may or may not have taken its steps in the ideal order. But the choice that does seem to have been correct was for Mr. Galinac and his father to follow their interests.

More specifically, the right choice was to nurture enough enthusiasm for those interests that they were willing to keep on following them, no matter what—until the shop had finally gone far enough that the pieces the shop needed for success had all the time necessary for those pieces to fall in place.

Related Content

Increasing OEM Visibility to Shopfloor Operations for the Win

A former employee of General Motors and Tesla talks about the issues that led to shutdowns on factory lines, and what small- to medium-sized manufacturers can do today to win business from large OEMs.

Read MoreArch Cutting Tools Acquires Custom Carbide Cutter Inc.

The acquisition adds Custom Carbide Cutter’s experience with specialty carbide micro tools and high-performance burrs to Arch Cutting Tool’s portfolio.

Read MoreBavius Technologie Appoints New President, Schedules Technology Showcase

Roy D. Cripps will lead the team at Bavius as it aims to expand its current business in aerospace structures and develop new market segments. Additionally, the company will showcase its technology during an open house event on June 11.

Read MoreHow a Custom ERP System Drives Automation in Large-Format Machining

Part of Major Tool’s 52,000 square-foot building expansion includes the installation of this new Waldrich Coburg Taurus 30 vertical machining center.

Read MoreRead Next

Video: Five-Axis Milling On Linear-Motor Machining Center

Linear motors take the place of ballscrews on this machine performing high speed cutting of aluminum at a job shop near Atlanta.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More