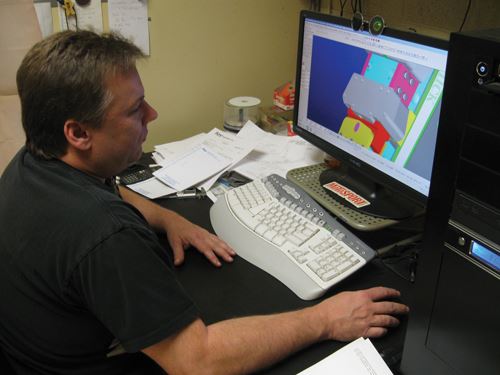

Joseph Szpak, Jr. founded his shop, Szpak Manufacturing, to engineer and build custom fixtures. Through the 1990s, production machining work took off, becoming the mainstay of the shop’s income. This change concerned Mr. Szpak, who knew that the types of parts his shop was producing could easily be shifted to a lower-cost country. Determined not to let his shop be vulnerable to international competition, he returned his shop’s focus to custom fixturing. It was the best decision he could have made.

Today, the shop in Columbia Station, Ohio no longer has to look for work. Thanks to repeat business and word-of-mouth referrals, the shop’s capacity is steadily full. In addition to fixtures for machining centers, the shop also develops custom clamping and articulation devices for deburring and finishing systems. International outsourcing actually drives some of the demand for custom workholding, he says, because the work that remains here tends to be higher-value. That is, the work tends to require the complex or highly automated machining that makes use of the fixture engineering that Szpak Manufacturing provides.

Even the shop’s remaining contract machining activity makes this point. For one component the shop produces at a rate of only hundreds per year, Mr. Szpak invented a fixture (at his own expense) allowing several pieces to be loaded into one setup quickly, and allowing features to be machined at various angles. The multi-angle machining is particularly important, because the part includes features at different angles that locate in relation to one another. Through efficiency-related savings, Mr. Szpak has long since recouped his investment in the fixture, and he doubts the part will ever be offshored. For that to happen, the new supplier would have to make a similar fixturing investment.

This application illustrates one of various reasons why custom fixturing often makes sense, he says, and why customers come to him to have this tooling developed. In reflecting on various advantages that custom fixtures can deliver, he finds at least five types of challenges that call for something beyond vises and other off-the-shelf workholding devices. Those challenges include the following:

1. Related features at different angles

Photo 1 shows the in-house fixture mentioned above. The part has machined features that locate with respect to features at other angles. The fixture, for use with a rotary indexer, clamps the part in a way that preserves access to various machined surfaces within a single cycle. Mr. Szpak extended the efficiency of the fixture by designing it to hold several pieces at once.

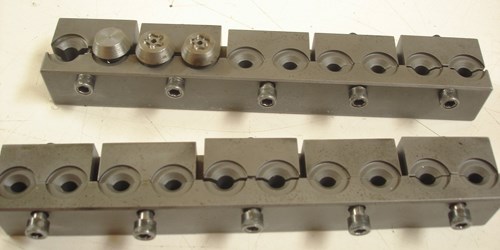

2. Many pieces in one cycle

The simple part in Photo 2 does not need custom fixturing, and was originally run without it. The only machining is milling a wrench design on the head of the screw. The problem was that loading this part proved more time-consuming than machining it. Creating a custom fixture to hold several pieces at once solved this problem by cutting the setup time per piece. Now, 10 pieces can be loaded in one fixture during the time while 10 others are being machined in a fixture just like it. The delay between machining cycles consists of just swapping in the fixture as a single unit.

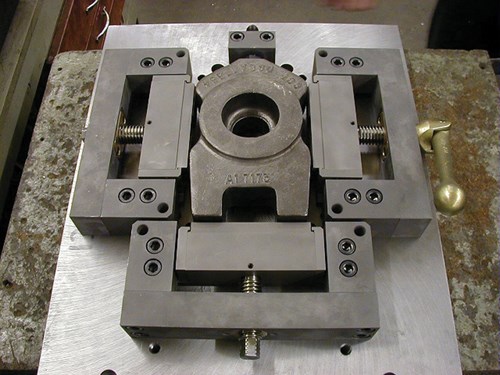

3. Avoiding operations

The process for the part clamped in the fixture in Photo 3 used to involve sawing a separate blank for each individual workpiece. The sawing was unnecessarily time-consuming. The fixture seen here reduces the amount of sawing per piece, because a single long strip is loaded through all four clamping points. Milling passes within the NC cycle quickly separate the strip into four sections, which then remain clamped for further machining.

4. Accuracy

The part in Photo 4 was clamped in a vise, but was prone to sliding enough to break a tight squareness tolerance. The cheapest solution involved keeping the vise, but equipping it with a customized restraint that keeps the part in place.

5. Parts that can’t otherwise be held

Finally, there are parts so fluid in shape that they cannot be held without some kind of custom clamping. In Photo 5, the only machining this part needs is drilling at two angles, but clamping the part to perform this drilling requires a custom fixture for an indexer. Castings and forgings often have similar custom fixturing needs. Another example is shown in Photo 5a.

Error Proofing

Mr. Szpak says one additional advantage of custom fixturing is an aspect of nearly all his fixturing projects: Error avoidance.

A well-designed fixture ought to prevent the part from being loaded incorrectly, he says. The challenge is not to implement this prevention—doing this can be as easy as adding a dowel in the right place. Instead, the challenge of error prevention is anticipating all the possible misloadings. People who design a part, he says—as well as the people like him who design its fixturing—often are blind to the many ways the work can be loaded wrong. Experience has taught Mr. Szpak to open his imagination, searching for the various possible misloadings that a given fixture design needs to prevent.

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)