Molding Personnel

This mold shop has a full-time employee devoted to nothing but training.

Share

Machinist. Programmer. Teacher.Those are three tool-and-die shop professions—or maybe not. Most shops don’t have the third one: teacher. To almost any company that makes molds and dies, that profession would seem out of place.

Ryan Pohl certainly had days when he felt out of place. He left the public school system to rejoin the company that employed him before he became a teacher—Commercial Tool & Die of Comstock Park, Michigan (near Grand Rapids). He returned there to pioneer the new and unprecedented position of “training coordinator” for this 130-employee mold shop. Other employees would engineer, machine and assemble molds; he would develop course materials and teach classes. In a market as competitive as mold making in Michigan, such a position—paying someone to do work such as this—seemed extravagant. Not every employee saw the point. Once or twice, Mr. Pohl was even called a word that cut to the very core of how some coworkers viewed his job. He was called ... “overhead.”

However, the company was starting to hire employees for shopfloor positions who had no formal machine-shop training. It had to do this because the skilled employees were getting too hard to find. With so many employees arriving untaught, hiring a teacher seemed like a natural step. Indeed, when company management considered the matter closely, it became clear that training unskilled employees in a less disciplined way that did not involve formal instruction resulted in overhead cost of its own—cost that could be quite high.

Mr. Pohl recalls an incident where an employee left another line of work and came to CTD determined to succeed. His attitude was excellent. However, he did not initially possess even some of the fundamental skills necessary to assimilate the more advanced tasks he was shown on the shop floor. His training was disorganized, taking the form of shadowing or working alongside a variety of experienced employees. Five months passed before he became discouraged and quit. In other words, the experience was a 5-month detour for this employee and a 5-month investment of time and money that CTD never recovered.

That was several years ago, during the time when Mr. Pohl worked for the shop as a CNC machinist. He left to get a degree in teaching, then worked for 2 years as an instructor in a vocational high school. During this time, he still worked for CTD in the summers—and he talked to CTD’s management about an idea for building a formal training program within this shop.

That training program is a reality now. Though it is still young, it has developed to the point that at least some of the positions in the company can now make use of less-skilled employees with much less investment and much less risk. About 10 employees have gone all the way through the program so far. All are succeeding. Gone is the possibility of 5 months of struggle and uncertainty ending in frustration. The break-in period now is about 3 weeks. After 3 weeks within the machinist program, for example, a student who came to the shop with no formal training can be expected to obtain his or her own cutting tools, perform setup, run NC programs and even perform some minimal programming. In other words, after just 3 weeks, the formerly unskilled employee is now much more skilled. Instead of being a source of “overhead,” the employee is already functioning as a productive asset on the shop floor.

That training program is a reality now. Though it is still young, it has developed to the point that at least some of the positions in the company can now make use of less-skilled employees with much less investment and much less risk. About 10 employees have gone all the way through the program so far. All are succeeding. Gone is the possibility of 5 months of struggle and uncertainty ending in frustration. The break-in period now is about 3 weeks. After 3 weeks within the machinist program, for example, a student who came to the shop with no formal training can be expected to obtain his or her own cutting tools, perform setup, run NC programs and even perform some minimal programming. In other words, after just 3 weeks, the formerly unskilled employee is now much more skilled. Instead of being a source of “overhead,” the employee is already functioning as a productive asset on the shop floor.

Teaching And Machining Are Different

The training program, called Commercial Tool University (CTU), has different courses with regular classes. Unlike a typical university, though, these classes are held in a meeting room or break room. Students are evaluated through both written tests and hands-on applications. The program even has faculty apart from Mr. Pohl. A complement to the course instruction is hands-on training on the shop floor, which is overseen by a formally designated trainer in every department. Mr. Pohl has worked with these trainers to teach them what he can about how to teach.

“People think teaching is just a conversation between someone who knows and someone who wants to know,” he says. “It’s more than that. It’s a structured conversation. It has to have an organized series of steps and a definite objective in mind.”

Not everyone is a good teacher. A good machinist is not necessarily an effective machining instructor—these are two different roles. Many shops expect less-skilled employees to pick up what they need to know entirely from more experienced employees on the shop floor. If this expectation might have succeeded in the past, modern lead times alone can make it problematic today. In a successful mold shop, the work moves so fast that a machinist rarely has the time to do justice to instructing a junior employee.

For CTD, yet another reason why the company favored a more formal training program was consistency. The shop has a philosophy of finding what works and standardizing on it. For example, all of the shop’s boring mills come from Kuraki. All the finish milling machines come from FPT. All the EDM machines come from Makino. All the machining centers making mold components come from OKK. The shop wanted to see this same kind of uniformity applied to the skills, knowledge and procedures imparted to shopfloor personnel, including the personnel who would be running those machines.

In fact, those machines offer part of the reason why Mr. Pohl long believed that this company was a natural venue for training—more natural than a school. The machine tools and other manufacturing resources are nothing like what a trade school could imagine possessing. A typical trade school depends on donations to keep the school’s equipment just somewhat current, and those donations are declining. CTU, by contrast, has access to the latest CNC equipment. In fact, students here have access to the very machines they will be using as soon as their training is done.

“As a vocational school teacher, I did weekly industry visits to try to keep myself current,” Mr. Pohl says. “Now, I walk around in the most current practices every day.”

Legwork

“Walking around” in those practices is essentially how Mr. Pohl created the course materials, and even how he defined what the courses should be. The mold shop did not have pre-existing course curricula lying around, so Mr. Pohl had his work cut out for him.

He worked at the jobs that others would eventually be trained to do, just so he could document every task and procedure. He worked with plant manager Dave Ketelaar and CNC machine department foreman Fred Longcore to decide which procedures needed to be taught. Then, Mr. Pohl started outlining courses and composing the PowerPoint presentations that would be used in teaching various classes. He spent many months as training coordinator before he ever taught a class.

The course list is still growing. Plenty of disciplines and departments in the company still have not yet been included in CTU—but they will be.

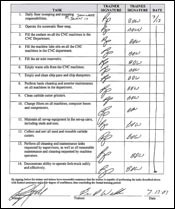

The kind of knowledge that has to be demonstrated as part of a particular class is illustrated by the document shown on page 89. The signup sheet captures some of the tasks in a starter class on CNC machine maintenance. Following a philosophy of “mastery learning,” CTU requires students to master all required tasks before the student passes a class. Question-and-answer tests are also part of every class, and the minimum acceptable passing score is 100 percent.

“Our customers won’t accept 70 percent as a passing grade for a mold, so we can’t set up our training program to work that way, either,” says Mr. Pohl.

Journeyman Certified

Employees pressed the company to see whether there was a way that their CTU study could apply to obtaining journeyman’s cards. Mr. Pohl discovered that this was indeed in the cards (so to speak). He contacted the Federal Department of Labor. A representative came to the shop and worked with him on structuring the program so that it could qualify for federal certification. CTU thus became more “official.” The entirely in-house training program is now a way to achieve a moldmaker or CNC machinist journeyman’s card that is recognized in any other shop.

Other than the chance for this card, there is no incentive built into the training program. That is, there is no financial encouragement for employees to increase their skills and knowledge in this way. Employees can’t train their way to higher levels of pay—at least not in any defined and mechanical way. Such an incentive program might come later. Then again, it might not.

The company has a culture in which less-experienced employees are generally enthusiastic to participate in the training. Using shopfloor PCs to review course materials while a machining cycle runs is commonplace. The best thing for CTD may simply be to value this culture and keep it alive.

Occasionally, there is grumbling. An employee may ask, “Why do I have to go to a class?”

However, Mr. Pohl says that the employees who are accustomed to trying to pursue skills education on their own—that is, in a community college and on their own time—are quick to respond to the grumblers.

“You don’t know what you have,” they say. “You punched in to go to class.”

Related Content

Same Headcount, Double the Sales: Successful Job Shop Automation

Doubling sales requires more than just robots. Pro Products’ staff works in tandem with robots, performing inspection and other value-added activities.

Read MoreFinding Skilled Labor Through Partnerships and Benefits

To combat the skilled labor shortage, this Top Shops honoree turned to partnerships and unique benefits to attract talented workers.

Read MoreManufacturing Madness: Colleges Vie for Machining Title (Includes Video)

The first annual SEC Machining Competition highlighted students studying for careers in machining, as well as the need to rebuild a domestic manufacturing workforce.

Read MoreInside Machineosaurus: Unique Job Shop with Dinosaur-Named CNC Machines, Four-Day Workweek & High-Precision Machining

Take a tour of Machineosaurus, a Massachusetts machine shop where every CNC machine is named after a dinosaur!

Read MoreRead Next

Engineering Employees

Today, the lack of skilled manufacturing employees is the major problem holding this company back. To clear the way for growth tomorrow, the company is determined to solve this problem. The answer is an internal university for developing the skills of every current employee and new hire, including many who have never set foot in a machine shop before.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More