MMS Looks Back: 1960s - The Radical Becomes Practical

Stories about whether to adopt numerical control reveal the value of careful consideration over wholehearted embrace or outright dismissal of new disruptive technologies. This story is part of our 90th anniversary series.

Share

Hwacheon Machinery America, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

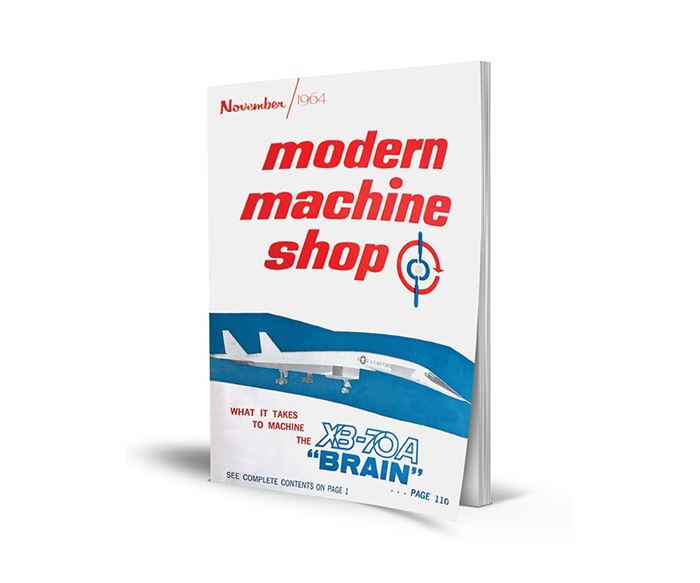

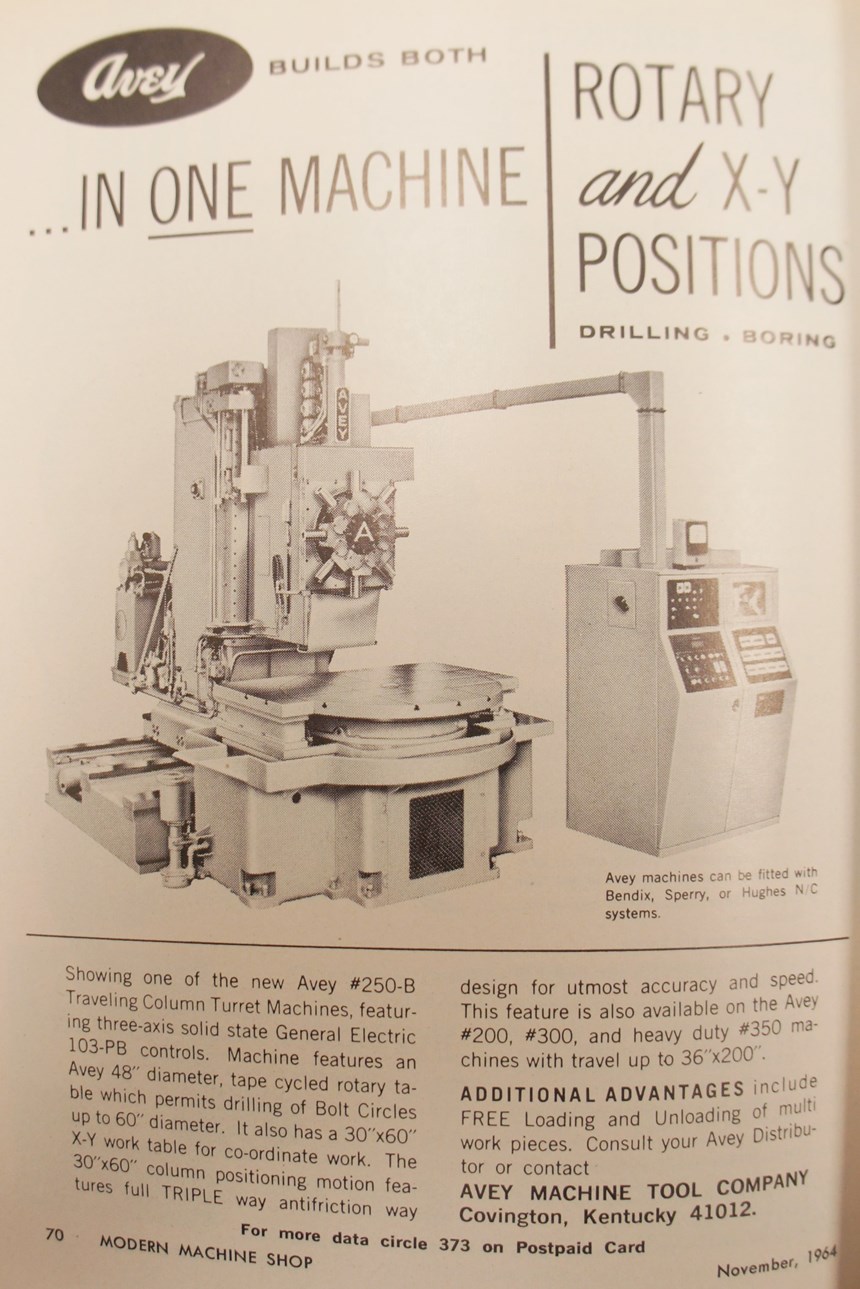

Known mostly for sweeping cultural and political change, the 1960s also were shaped heavily by machining technology. Pastel-toned Modern Machine Shop issues from that decade feature images of jets and rockets, evidencing the primacy of the space race and the Cold War and the associated need to deal with new materials and material requirements. The first articles appeared about industrial lasers , and about electrical discharge machines (EDMs) that could cut with wire rather than solid electrodes. Perhaps most notably, the first MMS issues published without ads on the cover were also among the first to regularly dive deep into numerical control (NC) technology. Running mostly on perforated tape, NC machine tools were becoming small and inexpensive enough to change life within the shop as radically as new attitudes and ideas were changing life outside it.

“There is the likelihood of a bleak future” for shops that do not stay abreast of the latest NC developments, wrote then Editor-in-Chief Fred Vogel in November 1964. And yet, even in a column surrounded by editorial and ads alike cheerleading NC’s proliferation, his tone remained measured. “It would be foolhardy to quickly discard those processes that have proven themselves for the past century and enjoy many inherent advantages,” he continued. “There is a real need for both the new and traditional, and the wise production man will coolly evaluate each situation and make his choice based on facts and not emotion.”

Mr. Vogel’s words are as applicable today as when he wrote them more than half a century ago (likely on a typewriter). Granted, he could not have predicted the rise of additive manufacturing when he wrote that “There is no substitute for either the man or his simple machine where he can produce the spare part, the variation, the modification, the one of a kind, the experimental piece, the parts not applicable to the tape machine, the shop that stresses flexibility and ingenuity with all types of equipment, and so on ad infinitum.” Nonetheless, manual mills and lathes have not been eliminated as staples of many toolrooms, and it was not long ago that the very idea of doing so would have been laughable. As for more sophisticated computer numerical control (CNC) equipment, few shops have abandoned milling or turning in favor of additive technology, which is generally considered more of a complement than a rival to traditional processes.

That is the case for now, at least. An uncertain future provides good reason for shops of all stripes to stay abreast of additive technology developments like new material capabilities or faster processing of larger parts. However, the latest, most advanced systems are not always accessible or desirable in the near term (or ever, in some cases). In the meantime, savvy business owners cannot be distracted by curmudgeonly naysayers nor by zealous technological missionaries. Decisions must instead be informed by deep understanding of a technology’s current capabilities and limitations as well as the hurdles faced by the earliest experimenters and adopters.

In the November 1964 issue, such practical thinking is evident beyond Mr. Vogel’s column. The cover, touting the machining of the mechanical “brains” for the flight-control system of the XB-70A supersonic jet prototype, makes clear that this publication is dedicated to the most sophisticated and modern machining applications. However, a primary message of this particular 1960s aerospace application story was that NC was not for everyone. “Perhaps the most amazing” aspect about producing the flight-system components, the article states, was that most work was done on “rather conventional shop machines and grinders, with setup techniques and accurate gaging assuring the necessary precision.” Listed specifications included machining within 0.0002 inch for non-sensitive components and 0.0001 inch for others; flatness deviation of no more than 0.00005 inch on some parts; and axial deviation within 0.00001 inch on certain bearings.

The very next page debuted the first article in a four-part series on NC, but the tone was anything but breathless. Building on another series of NC articles published three years earlier in 1961, “Let’s Again Discuss Numerical Control” was presented as an “eat your vegetables” kind of refresher on a burgeoning technology that shops would ignore at their peril. “One of the first hurdles to the widespread acceptance of NC was a lack of comprehension about the concepts on which it is based” states the guest author of the first piece, which covered the importance of the Cartesian coordinate system for ensuring that “dimensioning language means precisely the same thing to the programmer as it does the design engineer, the draftsman and the setup man.”

Ensuring everyone involved in production operates from the same data interpreted the same way? Some things, it seems, never change. And when they do, shops eager to cast their gaze to the horizon should also be sure to keep one foot on the ground.

Related Content

4 Commonly Misapplied CNC Features

Misapplication of these important CNC features will result in wasted time, wasted or duplicated effort and/or wasted material.

Read MoreContinuous Improvement and New Functionality Are the Name of the Game

Mastercam 2025 incorporates big advancements and small — all based on customer feedback and the company’s commitment to keeping its signature product best in class.

Read MoreThe Power of Practical Demonstrations and Projects

Practical work has served Bridgerland Technical College both in preparing its current students for manufacturing jobs and in appealing to new generations of potential machinists.

Read MoreCan ChatGPT Create Usable G-Code Programs?

Since its debut in late 2022, ChatGPT has been used in many situations, from writing stories to writing code, including G-code. But is it useful to shops? We asked a CAM expert for his thoughts.

Read MoreRead Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More