Mass Producing Quantities Of One

It may sound like a contradiction in terms, but this Windsor, Canada, shop developed a production system for making prototype and limited production quantities of mold and die sets based on assembly line techniques. It's a concept that scales up or down and is applicable in a wide spectrum of shops.

Share

Prior to the application of the assembly line to automotive manufacturing, cars were built in place with various parts manufactured to fit the car being built. Basically it was a sequential operation in which the assembler was responsible for fit and finish of the various components.

Then came the assembly line with its high degree of organization and specialization. Organization involved manufacturing coordination of the various parts, subassemblies and components in a way that insured their arrival on the line at the right time and in "line-ready" condition—meaning they fit.

Specialization meant that instead of an assembler for each car, there was an assembler for a specific area of the car. As the line moved past, these assemblers took care of a small percentage of the overall automobile.

As a result of implementation of the assembly line, car production went from days and hours to minutes. Of course we know more now about the impact of carrying assembly line production too far. The process has been modified to better accommodate the human element and much automation has been added.

However, as a manufacturing concept, the key tenants of organization and specialization apply today as they did 90 years ago. Steve Reko, founder and president of Reko International Group, embraces this concept and successfully applies it to manufacture of molds and dies—primarily for tier one suppliers to the automotive industry.

He believes that it's purely coincidence that assembly line manufacturing, as a concept, is linked almost exclusively with high volume manufacturing. Rather, he has successfully grown his business from conception 20 years ago to a growing 500-person operation by using the concepts of assembly line production to make mold and die sets.

Mold Maker As Metal Cutter

Mr. Reko is a master mold maker. He was trained in Europe and learned the traditional mold and die making craft which, as it turns out, bears striking resemblance to the way automobiles were once built.

"When we built a mold, the mold maker was like a god," says Mr. Reko. "We made all the decisions about how the mold would be built. There was little or no discussion about alternative ideas or methods. If I said burn that cavity with EDM it was burned. Maybe it could have been milled but it didn't matter. The mold maker was equivalent to the auto assembler of old."

"A down side of the mold maker dependent system," continues Mr. Reko, "was that the knowledge of how to build and often to some extent design molds resided in the mind of the mold maker. If something happened to the mold maker, a company could find itself in serious trouble."

When Reko Tool and Mould started business one of Mr. Reko's goals was to eliminate, as much as possible, his new company's dependence on traditionally trained mold makers. "I decided to build my business around metal cutters," says Mr. Reko. "After all, that's what making a mold or die is about."

Birth Of A System

The model for Mr. Reko's new shop is Henry Ford's assembly line. Its key contribution to manufacturing science was division of labor. By breaking an assembled product down to a basic and common subset of manufacturing steps, and arranging those steps to occur simultaneously, any product, be it automobiles or molds and dies, can be built in significantly less total time than with conventional sequential operations.

Even though making a unique set of molds or dies seems fundamentally different than mass producing millions of copies of the same item, basically the manufacturing processes line up surprisingly well.

Key to successfully mass producing a product in huge quantities or in quantities of one is to plan the manufacturing in detail, off-line. "Every possible manufacturing contingency must be allowed for to make the system hum," says Mr. Reko. "In practice, the more complex a product is, from a manufacturing and assembly perspective, the better this system works. My goal is to get every design detail and the subsequent manufacturing requirements for each detail in place and planned before a single chip is cut."

The process engineering group gets the mold and die making ball rolling at Reko. The tool design work begins from imported part drawings. They have seats of software to match those from their tier one suppliers. These teams create complete tool set designs, including all pins, dowels and details. When the design team finishes its work, the tools are shop ready.

After the tool design work is complete, another process engineering team determines the manufacturing process steps needed to complete the job. Reko has developed a software package for internal use, which is essentially an operational check list.

The shop operations are divided into departments including tool room, machining, EDM, measurement and polishing. Within each department increasingly detailed menus break the operations into finer process steps.

The team then assigns the various mold and die components to departments and even specific machines. For example, if an EDM burn is needed on a tool, the electrode cutting department is alerted to schedule production to coincide with the mold build schedule.

When the manufacturing steps are identified and entered into the system, a costing team assigns hours to the job. Because the entire mold and die production process is broken into relatively small increments, costing is simplified. No single manufacturing step, if underestimated, can adversely affect the job's overall profitability.

These three detailed pre-production steps, design, build plan and costing make the system work. "If the engineering plan is correct," says Mr. Reko, "the rest of the job simply involves cutting different geometries using the performance attributes of CNC machine tools."

On The Shop Floor

An assembly line is like a flowing river. It represents the sum of all the tributaries that feed it. Likewise, the production flow at Reko is based on that model. Inter-shop communication is the enabling technology for coordinating the manufacturing tributaries that ultimately meet on the assembly floor.

"Because of the up-front process engineering work," says Mr. Reko, "the EDM department knows when it needs to prepare electrodes, machining knows when it needs to have mold or die pieces ready for the assembly floor, measurement knows when to schedule inspection time. Doing the detailed planning up front reduces surprises and creates a consistent method for the ancillary work to flow smoothly into the main stream for the mold or die production."

Mr. Reko gives credit for this smooth production flow to electronic communication tools. The shop is wired to communicate electronically using DNC to the machines and scheduling links from process engineering to the various manufacturing departments. "Everyone is kept on the same page," says Mr. Reko.

Mr. Reko's "Kids"

The median employee age at Reko is relatively young—under 30. "I hire these kids specifically because they don't have experience," says Mr. Reko. "I have the opportunity to train these young people to use our system rather than re-train more experienced workers who may have other systems to unlearn. It astounds me how well these people take to the job and the system."

Admittedly, this method goes somewhat against conventional wisdom. Rather than rely on a few very knowledgeable individuals, this shop breaks its knowledge and skill sets into small specialties. Each person is responsible for a specific aspect of the mold or die set manufacture and once that task is complete the job moves to the next specialist who does his or her work. On the surface it sounds a little bit stagnate.

However, cross training and additional skills acquisition are encouraged. Continuous training and skills upgrade are an integral part of Mr. Reko's system. More experienced personnel teach those less experienced.

In the metal cutting department, for example, machine tools are arranged in tandem. For example, a relatively small vertical CNC machining center might be located next to a much larger bridge-type or portal machining center.

The idea of this arrangement is two-fold. First, the vertical is used by a less experienced operator to run relatively simple mold or die parts that go with the cavity or core running on the larger machine. A second benefit is that the interaction between the two machinists results in exchanges of ideas and experience—training takes place.

In the engineering area, a different but effective process is used to capture the thinking and knowledge of the designers. As a mold or die design is created, the designer, using voice tape and video, records each step of the design with explanation and illustration of how different problems were attacked and solved. Again, a two-fold benefit is derived because the tapes serve as a record for the job and a case study training aid for less experienced designers to learn more.

The System For Everyone?

The relative merits of Mr. Reko's application of assembly line techniques for production of dies and molds are seen in increased throughput and better accuracy. Rarely does a mold or die set see the try-out press more than twice. "If the design is right, the machine tools are good quality, and the operators perform their metal cutting tasks correctly," says Mr. Reko, "it should not be a surprise when theirs no blue on either core or cavity when tried out."

Using a mass production technique to make very low volumes has led this company to success. Will it work for other companies? "In most automobile manufacturing," says Mr. Reko, "the production consists basically of planning simultaneous, off-line build of components and subassemblies and timing their completion to hit the correct base model as it moves through assembly. It doesn't matter if volume is 15 cars a day or 500, the system is scaled to fit the volume. At Reko, we've simply borrowed this concept from car production and applied it to making mold and die sets. It works well for us and I believe it will work just as well for others."

Related Content

How to Successfully Adopt Five-Axis Machining

While there are many changes to adopt when moving to five-axis, they all compliment the overall goal of better parts through less operations.

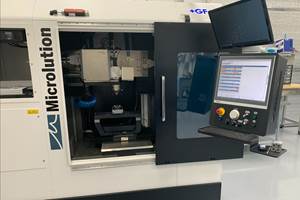

Read MoreWhere Micro-Laser Machining Is the Focus

A company that was once a consulting firm has become a successful micro-laser machine shop producing complex parts and features that most traditional CNC shops cannot machine.

Read MoreOrthopedic Event Discusses Manufacturing Strategies

At the seminar, representatives from multiple companies discussed strategies for making orthopedic devices accurately and efficiently.

Read MoreInside the Premium Machine Shop Making Fasteners

AMPG can’t help but take risks — its management doesn’t know how to run machines. But these risks have enabled it to become a runaway success in its market.

Read MoreRead Next

Manufacturing Molds

CNC surface grinding is a critical component of this shop's systematic approach in the manufacturing of multicavity molds to extremely high tolerances.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More