Improvement Is Not Optional

No matter how busy this shop gets, it continues to pull teams of employees out of production so they can focus on solving problems to make incremental process changes. The advances add up. Today, this is a very different shop than it once was.

Share

Walk into Byrne Tool + Design and, if you have spent time in mold shops, you sense at once that this mold shop is different from others.

Why is this?

The answer is not immediately apparent. Machining centers and EDM machines make cores and cavities. Employees tend those machines and assemble finished molds. That much is the same as in any other moldmaking facility.

But look more closely and the differences come into view. In this shop, there are no individual toolboxes—standardized workbenches have replaced them. There are no computers for CAM programming near the machines, but instead there is a set-apart programming station where employees come together. Nor is there seldom-used legacy equipment or tooling taking up space, because what isn’t used has been cleared away.

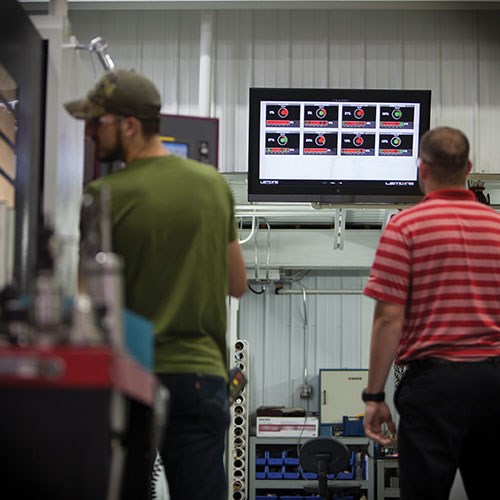

On the machine tools in this shop, there are no blueprints affixed with magnets or even any greaseboards. Machines instead have touchscreen monitors providing access to job information in Google Docs. And above the shop floor, no banner proclaims a slogan. Instead, large monitors show real-time graphical displays of machine-tool utilization.

All of these developments, and many others like them, are less than a decade old. In fact, most of them are considerably more recent than that. Just over 10 years ago, this was a very different shop, says Byrne Tool + Design Operations Manager Andrew Baker. It was essentially a captive shop, getting nearly all of its business from a sister company making power and data hardware for business furniture. Byrne was also an inefficient shop, he says, though he would not have thought of it that way at the time.

Today, the shop is spacious and clean. It has reinvented itself to cater to a particular type of customer: design-oriented OEMs with tight leadtime demands. The shop’s process is disciplined and streamlined enough to reliably surpass the expectations of this class of customer, and as a result, the shop is no longer captive. Business today comes from industries including automotive, consumer products and medical devices.

Throughout the pages of this article, photos illustrate various manufacturing improvements that Byrne has made. Some of the improvements are large and some are small. Some are simple and some are unusual. The reason why pages of photos are the best way to convey the shop’s advance is because not one of these improvements by itself would be enough to set the shop apart. Instead, what has transformed this shop over time is the commitment to keep making the effort and taking the time to conceive and implement changes such as these, no matter how heavy the normal workload gets. That commitment—keep improving no matter what—is this shop’s simple secret.

“Common sense manufacturing,” or CSM, is Byrne’s term for this commitment. Any recurring cause of error, delay or inconsistency in the process is a potential candidate for a “CSM event” in which a team of employees breaks away from regular production in order to focus its attention on one problem and recommend a solution.

For every CSM event, the mix of employees is different. The solution they recommend might entail a hard investment or a departure from old habits. The culture of this shop has grown accustomed to the fact that any procedure or piece of equipment on the shop floor might change in order to overcome an identified inefficiency. More importantly, the culture has changed to expect CSM events as a non-negotiable priority. Every employee is a potential participant in a CSM event, and even the employees not involved in a given CSM event still support it, because they are covering for the team members who are not available for work on the shop floor throughout the two- to three-day event.

“We want eight to 10 CSM events per year,” says company General Manager Tim Warwick. Continual improvement is not optional, no matter how busy the shop gets.

One of the most recent changes is the shop’s name. Byrne Tool + Design is the former Byrne Tool & Die. The new company name is written with a plus sign instead of an ampersand, because the “+” has become the company’s brand. The idea is that the company will be a tool shop “plus” something more, say company leaders, and that “plus” is likely to be different for different customers and to change over time. The very same mindset also fits the company’s new perspective on manufacturing, in which the search for the next incremental “plus” in shop performance has become a routine part of operations.

Mr. Baker says it all began very simply, with a commitment to implement the basic lean manufacturing practice of 5S. The mandate to adopt 5S came from above, he says, and he admits that he and the rest of the shop followed along only halfheartedly. Things changed when the results of this practice directly brought new business the shop otherwise would not have won.

Beyond Toolboxes

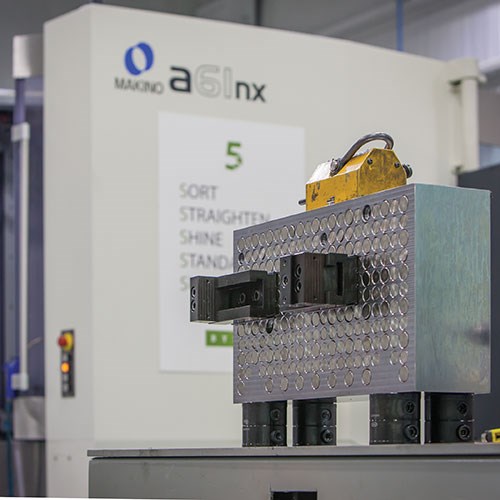

“Do you want me to make molds or do you want me to clean?”

That objection, or words to that effect, haunted the entire first year of Byrne’s attempt at lean manufacturing. 5S, which commonly stands for “shine, sort, simplify, standardize and sustain” (and can be seen in the photo above to stand for something close to this at Byrne) is the lean-manufacturing practice of organizing the workplace so that needed tools are easily found and easily put to use. To the employees accustomed to Byrne’s previous level of organization, implementing 5S seemed like needless fussing.

The sister company that makes office furniture hardware is Byrne Electrical, which was the source of nearly all of the shop’s moldmaking work until that business dramatically declined in the early 2000s. Just after the dot-com crash, office furniture was suddenly not a lucrative business to be in.

At that time, the owners of the Byrne companies committed both businesses to lean manufacturing. For Byrne Electrical, this would be a way to achieve much-needed cost savings. Byrne Tool & Die’s team members felt dragged along in this commitment, Mr. Baker says, because they expected to find work in other industries to make up for the decline in the furniture-related business. What they did not yet realize was how valuable lean would be in the effort to do this.

One development in particular brought this realization home. Despite internal resistance to 5S, Byrne succeeded over the course of nearly two years at getting the shop better organized and strikingly cleaner and tidier than it used to be. A prospective customer who quietly visited around this time toured the shop and gave no sign of his impression—until he later awarded his company’s considerable moldmaking business to Byrne.

In an email, he explained the reason for his decision. The European owners of his own company had fastidious standards, he said. Byrne Tool & Die was not the cheapest moldmaker he had found, but it was the only mold shop he had visited that was clean and organized enough that he could imagine showing it to his superiors with pride.

Mr. Warwick says he printed out several copies of that email. He made sure that everyone in the shop saw it.

Meanwhile, a second development revealed the power of process improvement and the extent of the Byrne team members’ ability to make change. In the course of the shop’s progress toward greater organization and standardization, Mr. Baker says there came a point when the team had to confront one of the shop floor’s greatest sources of variability: individual employee toolboxes. These toolboxes were inherently unorganized and they certainly were not standardized, he says. Allowing every shop employee to possess a self-created and self-organized workspace produced a system of needless complexity, clutter and, in many cases, redundancy. In keeping with the aim of simplicity, this system had to be replaced with a system of standard workbenches, in which some tools were removed from individual work areas altogether and instead placed within reach at the point of use.

Of course, this change was the step in 5S that met with the greatest resistance of all.

Byrne obtained new, standardized workbenches that came mounted on wheels. The promise to each employee was that these benches could be wheeled over to the machine tools, just like the individual toolboxes had been. That is, if employees wanted to use these standard workbenches as the basis of personal work areas near the machines, they could do that.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, in spite of the wheels, these benches have practically never budged. The staff discovered that in fact it is more useful to keep the individual benches clustered together in pairs, creating a double-size surface that multiple employees can share. The large surfaces not only provide for expansive working space, they also facilitate communication and collaboration because employees doing their work now come together at these combined tables. Thus, the aim of tidiness through standardization was achieved, and along the way, the shop also realized a system that works better to a surprising degree. The consensus throughout the shop is that the added bench space plus the aid to communication makes tasks easier to such an extent that work in general flows more easily.

That development was eye-opening. Individual toolboxes had been a deeply ingrained and long-standing part of the shop’s culture. Seeing this inefficiency overcome showed the shop’s team that it could overcome practically any other inefficiency as well. Even if the price of an improvement was an uncomfortable cultural change, the shop could make that change and see everyone through to the other side of the discomfort. Then, after the transition was past, the shop would get to reap the benefits of the process improvement thereafter, benefits that were likely to be even greater than the shop could have anticipated before making the change.

Beyond Lean

It was soon after this improvement with the workbenches that the shop stopped talking in terms of lean and began talking and thinking instead in terms of CSM. Not everything that seemingly saves time or saves effort contributes to better manufacturing. After all, wheeling the workbenches to the machine tools would have been more “lean,” in the sense that this relocation would serve to minimize employee motion and effort. But part of the reason why the workbenches stayed grouped together is because the collaboration encouraged by the common space is valuable enough to be worth some added motion and effort.

That was the realization that led to one of the stranger features of this shop: a collective bank of CAD/CAM computers that looks like it ought to be called “CAM Island,” except that islands are what this shop used to have back when programming PCs were located at each of the separate machine tools. Again, programming tool paths right beside the machine tools is arguably efficient, because the employee who hits the start button on the current job doesn’t have to move far to begin programming the next one. However, Mr. Baker says the problem with this arrangement is that it leaves employees isolated. They don’t ask questions about seemingly small matters because no one is nearby to hear the question. Clustering CAM stations together addresses this problem, because it creates an open and easy context for communication. When one employee is programming a job at one of the computers, usually there are at least one or two other employees present who are programming a job as well. A little chatter is a natural part of this proximity, and technical questions get asked and answered as a natural part of this interaction. Knowledge is shared effortlessly, and that helps the whole shop.

What’s more, relationships improve, says Mr. Baker. No one notices this happening because the effect is so gradual. But because of the shared space and the shared forum for asking questions about programming, an employee who might feel comfortable asking just one particular coworker his questions might find his trust expanded to the rest of the staff as a result of various other coworkers providing helpful input within the conversation.

This kind of collaboration and this kind of trust are key to the ongoing success of CSM. Again, the entire system depends on some employees leaving the shop floor for days at a time while other employees do the day-to-day work in their place. This system works without resentment and without friction only because everyone trusts in the value of what these CSM teams are doing, company leaders say. The habit at Byrne is simply to treat the employees involved in CSM events as though they are on vacation. As strange as it might seem to cluster CAM stations together, or as notable as any process improvement in the photos throughout this article might seem, the cultural shift in this shop is actually the most significant development of them all. Every team member here understands that making molds is not the full extent of the work. Improving the process for making molds is also an expected part of every employee’s job.

Related Content

How I Made It: Amy Skrzypczak, CNC Machinist, Westminster Tool

At just 28 years old, Amy Skrzypczak is already logging her ninth year as a CNC machinist. While during high school Skrzypczak may not have guessed that she’d soon be running an electrical discharge machining (EDM) department, after attending her local community college she found a home among the “misfits” at Westminster Tool. Today, she oversees the company’s wire EDM operations and feels grateful to have avoided more well-worn career paths.

Read MoreFinding the Right Tools for a Turning Shop

Xcelicut is a startup shop that has grown thanks to the right machines, cutting tools, grants and other resources.

Read MoreHow to Pass the Job Interview as an Employer

Job interviews are a two-way street. Follow these tips to make a good impression on your potential future workforce.

Read MoreFinding Skilled Labor Through Partnerships and Benefits

To combat the skilled labor shortage, this Top Shops honoree turned to partnerships and unique benefits to attract talented workers.

Read MoreRead Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More