How CNC Led To Cells

Bringing CNC into a previously manual process set this shop on a lean path that has led to continuous flow production.

Share

Clippard Instrument Laboratory Inc. resembles an intermittent job shop. The high-mix, low-volume nature of its parts production—there are about 5,000 standard parts in its catalog—means that it is difficult for the pneumatic device manufacturer to implement “true” lean cells. Instead, the company uses its own brand of lean to make the production process increasingly more responsive.

This has specifically been true of the company’s secondary operations ("secondaries") department, and its move to CNC. With the appropriate blend of CNC turning equipment, gang-style tooling and dedicated personnel, the pneumatic device manufacturer has created value-adding cells that are now important features of its lean landscape.

Clippard produces pneumatic and electronic control devices, including cylinders, control valves, electronic valves, modular valves, fittings and hose for a breadth of industries. Founder Leonard Clippard opened doors in 1941 to the business that sons William and Robert Clippard now run. Its two Ohio facilities house around 235 employees. The shop’s relaxed family atmosphere (the owners are better known as Bob and Bill) has encouraged valued employees to stick around. The average tenure of a Clippard employee is 14 to 15 years.

“It’s not unusual to come across an employee who has been working here for 30 years,” says Robin Rutschilling, manufacturing operations manager at Clippard.

The company’s components serve vital purposes in dental, medical, general automation, packaging, fluid handling and material handling applications. For instance, its water drawback valve is an integral component of those dentist suction tubes that flush out water and rogue plaque without dripping on patients. Clippard’s electronic valves are also used in automatic blood pressure machines at hospitals.

Manual Mutation

For Clippard, the decision to upgrade to CNC technology for its turning operations was predicated on the need to produce families of small parts in a jiffy. Jim Shaw, CNC setup/programmer of secondaries at Clippard, can attest to the changing nature of turning at the shop.

“From when I started about 6 years ago, volumes are lower but there is a higher mix of jobs,” he says. “This means continual setups; I’m constantly switching over jobs.”

Part accuracies were getting tighter, too, which further called the previous production equipment into question. When confronted with the prospect of buying new equipment or revamping some additional, older manual machines that had been abandoned in the basement, Clippard did both.

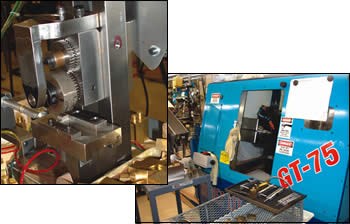

Consulting Mike Pasko, sales engineer for Richlin Machinery/Omniturn, the shop determined that retrofitting the manuals was a viable option that would be far less costly than acquiring a fleet of new CNC lathes. In June 2000, Clippard performed its first resurrection of one of the manual lathes, an electric hydraulic model originally manufactured by Hardinge. Much of the machine was salvaged, with an Omniturn kit bolted onto the existing bed.

“We removed the electric hydraulic controls and turret, which were no longer necessary and used the base, bed and headstock with spindle,” Mr. Pasko explains.

The shop also purchased two used Omniturn GT-75 CNC lathes. Three retrofit kits and one additional GT-75 later, the secondary department is settling into a more comfortable way of doing things. According to Mr. Rutschilling, CNC has been advantageous to this department on several fronts.

“We can finesse these machines to perform work that was simply not possible before,” he says. “The leap in part accuracy is notable. In fact, the CNC lathes actually surpass the precision requirements normally dictated by our customers.”

Clippard can now initiate changes on-the-fly without interrupting scheduled production. It has also been able to create a lean landscape in which employees can add even more value by completing other secondary operations while lathes run.

As Mr. Shaw explains, the accelerated cycle times themselves are significant.

“Even if we save 1 second on each part per day, we could process, say, 50 additional parts in one day,” he says. “This means getting more parts to the customers quicker.”

According to Mr. Pasko, the Omniturns are well suited to the part sizes—1/8 inch to 1 inch—that Clippard machines. Both the retrofitted manuals and the GT-75 lathes employ not only gang-style tooling, but also Omniturn’s control. The virtually identical capabilities let the shop place just about any job on any machine in the turning area. The old and new machines both typically process aluminum and brass, performing mainly internal work to modular valves and bodies of toggle valves. One way Clippard has been able to comfortably manage the frequent setups is by standardizing its gang-style tooling.

The Gang’s All Here

The gang tool arrangement allows for quick changeovers from one job to the next in multiple ways. For example, while running a job requiring three tools, the shop might receive a rush order for a job that would take one tool to complete. Mr. Shaw explains how he finesses the equipment to keep the part orders moving.

“Because there is an open slot on the tool bar, I can name this ‘tool four’ and modify the program,” he explains. “After changing the offset to tool four and changing the collet for the second job, I can run the rush part while the other job is essentially still set up. After removing this fourth tool, I need only recall the program for the first job, change out the collet and resume production.”

Perhaps more significantly, the whole tool bar—the whole gang—can also be changed. Using this tooling block, the operator can preset tooling for a particular part run and locate the bar on the tool plate (with the tools in it), and it’s ready to go. No time is wasted changing out tools.

Tooling space on a gang tool lathe is at a premium. To make the most of limited space, the shop uses Omniturn’s Multibar turning system, which consists of not only a quick-change holder but also multifunction inserts. These inserts save space because one cutting tool can complete multiple operations. For Clippard’s purposes, this means completing turning, grooving and facing operations while occupying one tool slot.

“The amount of tooling required, the geometry of parts and the operations needed in this application are perfect for gang tooling,” Mr. Pasko says. “There are only five to six tools required to complete a typical turning job at Clippard, so this makes sense. Now if you needed a substantial number of tools, perhaps requiring deep hole drilling, then turret tooling might be a better fit.”

No Idle Hands

Keeping setups manageable grants mobility to operators and setup personnel. No longer tethered to manuals, operators are more at liberty to venture out to load other machines or carry out other value-adding activities.

A new modular cell comprised of three separate manual machines takes advantage of this freedom. The machines are situated on wheeled carts, and the cell is adjacent to the row of CNC lathes. With this cell, during the 45 to 55 seconds that the CNC turning cycle might require, an operator can walk over to perform other secondary operations such as broaching a slot, drilling a cross hole or countersinking a hole for the part being run on the lathe. The operator can also carry out inspection with micrometers, calipers and functional gages.

In fact, there doesn’t even need to be any walking. At times, Mr. Shaw says he will wheel one of the mobile machines over to a particular lathe, so the operator can complete all of the operations for a given job without having to travel. During a shift, this could mean that 100 more parts are ready to be shipped.

Tools are located on a rolling cart, too. Mr. Shaw does tool setups, and the cart lets him float from machine to machine to accomplish setups quickly. Spending less time fetching tools means that he can focus on programming jobs, delegating work and actually setting up. The cart contains an organized assortment of all of his inserts, drills, gang toolholders and specialty collets.

“With this simple solution, I suppose we save many hours over the course of a year,” Mr. Shaw explains. “No time is wasted traveling back and forth to the table to locate supplies.”

Being able to complete value-adding activities this easily also fosters continuous flow. This means producing and moving one item or a small batch of items through a series of steps as seamlessly as possible. Accomplishing tasks with fewer impediments actually creates value by making the shop better equipped to produce small quantities responsively.

For Clippard, one enabling factor of continuous flow is automation. The process has been optimized with “Clippardization,” as the shop has integrated its own homegrown pneumatic bar feeders, air-powered chip blasters and parts catchers into both the new and the retrofitted machines. Innovations like these have allowed these machines in the secondary department to use some of their open capacity to perform primary operations as well.

For example, Sharon Flaum’s station (pictured on p. 74) is basically devoted to one part, a toggle valve body. While the GT-75 completes grooving, facing, threading, drilling and knurling on that particular part, Mrs. Flaum works on name rolling, chamfering, deburring and drilling.

The same lean logic has also been applied elsewhere in the facility, with CNC milling machines now mated to chamfer and deburr side stations.

Moreover, the idea continues to move forward. Now, the overall goal at Clippard is to keep developing cells in each department not just to integrate machining operations, but also to integrate manufacturing and assembly. The next step, the company says, will be introducing a “true” lean cell at its Fairfield, Ohio facility. This cell will carry out the production of the company’s cylinder heads—from start to finish.

Related Content

Tungaloy Expands Threading Tool Insert Offerings

The TungThread indexable threading tool series is designed for applications including general parts that are machined in CNC lathes and small precision parts in Swiss-type automatic lathes.

Read MoreWalter Ceramic Inserts Enable Efficient Turning, Milling

Suitable turning and milling applications of the WIS30 ceramic grade include roughing, semi-finishing and finishing, as well as interrupted cuts.

Read MoreNorton | Saint Gobain Abrasives' Wheels Increase Metal Removal

The Norton Winter Paradigm Plus Diamond and Winter G-Force Plus Next Generation Diamond Wheels expand the company’s grinding wheel options.

Read MoreWalter Turning Grades Reduce Machining Times

The WKP01G and WPP05G grades are ideal for continuous cutting and occasional interrupted cuts in high-tensile materials.

Read MoreRead Next

Get Lean, Go Global

A successful manufacturing company must achieve world-class capability within its walls. At the same time, a company has to go after global business opportunities. Hanel Corporation (New Berlin, Wisconsin) is a case in point. It has implemented several U-shaped production cells that help the company keep costs down and productivity up. At the same time, company leaders have aggressively courted customers in countries around the world by offering both tangible and intangible values.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More