Easy Does It

This shop specializing in small-scale parts says successfully machining tiny features into tiny workpieces is less about technology and more about technique.

Share

Patience.

Gentleness.

Really sharp cutting tools.

According to Mark Rohlfs of East Coast Precision Manufacturing in Killingworth, Connecticut, these are some of the things it takes to machine features smaller than the eye can clearly see into tiny and delicate parts.

Special equipment or technology is not what it takes, he says. His shop specializes in producing minuscule plastic parts for various customers and end uses. The shop routinely uses drills and end mills as small as 0.020 inch, and often uses 0.008-inch tools. However, the work is performed on standard machining centers using standard vises. The tiny cutting tools are held in toolholders that Mr. Rohlfs admits “are not even all that high quality.” In short, standard equipment can do the job if that equipment is used with care.

To provide a further sense of the equipment that is not required, this shop even lacks noncontact tool measurement. Some shops machining at such small scales consider this noncontact measurement to be essential, because the tools bend and break with little pressure. At East Coast Precision, however, tool offsets for all tools (even the 0.008-inch ones) are established by physically “touching off” at the machining center—that is, gently feeding into a solid surface and using a piece of paper as a feeler gage.

According to Mr. Rohlfs, such small cutting tools can be put to use with some of the same machines and same methods as larger tools, just as long as the small tools are not handled as roughly as most cutting tools are routinely handled. Delicate handling is the most important difference.

The same goes for the parts. They can also be damaged with slight force, so deliberate and gentle manipulation is a hallmark of this shop. No sudden moves, no forcing and no impacts—these are the objectives that shape how the employees of this shop do their work.

The result is a set of routine procedures in this shop that—though they are mainly common sense—nevertheless might seem strange to a more conventional shop that is used to taking full-size cuts into full-size metal parts.

Stay Sharp

In fact, East Coast Precision sometimes competes with shops accustomed to conventional-scale machining of metal. The shop can succeed at producing parts that cause these other shops difficulty, even when the other shops have access to comparable equipment. Mr. Rohlfs says shops accustomed to cutting metal tend to look at plastic and think, “How challenging can it be?” He says that holding precise tolerances at tiny scales in soft, springy and/or gummy materials can be challenging indeed.One of the keys to success is sharp cutting tools, he says. If the tools are not sharp, not only will cutting force and deflection increase, but so will the size of the burr. Burrs represent a constant, chronic challenge of machining small-scale plastic parts. If manual deburring is required—often unavoidable—then this can be more time-consuming than the machining cycle. However, in many cases the combination of sharp cutting tools and strategic tool paths can make it possible to eliminate any burr within the machining cycle. Even though the workpieces are plastic, the shop changes cutting tools frequently to keep them as sharp as possible.

Another key to precise and effective machining is unusual tool geometries. Apart from the CNC machine tools, one of the most important pieces of equipment at East Coast Precision is a benchtop manual cutter grinder. Using this, the shop can quickly produce a tool with some unusual set of cutting geometries to cut a particular feature more effectively. When standard tool geometries do not work, Mr. Rohlfs experiments with unusual geometries to find one that does. About half of the jobs the shop ends up running use at least one special tool.

One other consideration in machining tiny plastic parts effectively is to pay attention to the order of operations. The stiffness of the part is already slight, so cuts that further weaken the workpiece or make it less rigid should come late in the process. This is the same kind of thinking that is applied to other light and flexible parts at much larger scales. Aluminum aircraft components, for example, are also machined with an order of operations aimed at keeping the part as stiff as possible in the areas that still have to be machined.

This similarity in thinking illustrates something important about the small-scale machining, says Mr. Rohlfs.

As long as the tool is sufficiently sharp, the cut can be trusted to behave similar to machining passes at larger sizes. In other words, what happens at tiny scales is not mysterious. The main difference is simply that this smaller machining cannot be seen. East Coast Precision’s personnel rely on 10X magnification eyepieces just to look at finished parts. That is why, to determine the right custom tool geometry and the right order of operations, Mr. Rohlfs generally has to imagine how each machining pass is likely to behave. But when he imagines something like the way a steeper clearance angle on a particular tool is likely to work, he can trust that the pass will behave the same way that he would see it behave if the scale of his work was increased by, say, 10, 20 or 50 times.

Still, squinting through eyepieces is not the only unusual procedure here. Because the scale of the parts and tooling is smaller, the care taken by the shop’s personnel has to be that much greater. This shop routinely adheres to procedures that might seem fussy to other shops, but these procedures have proven essential for preserving the value of both the customers’ parts and the shop’s tiny tooling.

Small Considerations

Routine procedures in this shop include all of the following:- Cutting tools. Tools are always carried by hand instead of being placed in a cart. Tools are also kept isolated from one another, so the edges of different tools do not make direct contact. These procedures help safeguard against the tool getting a chip too small to see, but nevertheless big enough to dull the tool and scrap a run of parts.

- Workholding. Parts are held in soft jaws that are also machined out of plastic. A torque handle on the vise ensures that the vise is not overtightened.

- Machine tools. The shop’s Fanuc Robodrill machining centers are precise machines, but their positioning changes during the day. The positioning does not change by much, but it changes enough to matter when machining at tiny scales. An essential part of small-scale machining is simply to know each machine tool well enough to know how its offsets need to be updated as the machine gradually warms up during the morning. The same discipline applies to the shop’s CNC turning center as well.

- Inspection. A toolmaker’s microscope with 30X magnification is an important measurement and inspection tool here, but plenty of small-scale work is inspected using hand-held gages. Usually a shop considers the gage to be more sensitive than the part, but the opposite is true here. A micrometer has to be tightened slowly so that excess momentum in the barrel does not cause the gage to “clamp” the part. Something similar applies to gage pins used to measure holes. Even a slight push is too much force to slide a gage pin into a hole. Either the pin goes in without resistance or else the hole is too small.

- Cleaning. Parts cleaning often involves a clamshell strainer and a very

light stream of water. The shop takes great care to let the water

perform the cleaning without assistance, because physically stirring

the parts is likely to cause damage.

Seeing Green

The need to take care and stay focused is even reflected in the color scheme. Uncharacteristic of a machine shop, the walls of this shop are painted green.

This

was a conscious choice, says Mr. Rohlfs. He put some thought into it,

saying, “I thought green would be the most calming color.”

Related Content

How to Mitigate Chatter to Boost Machining Rates

There are usually better solutions to chatter than just reducing the feed rate. Through vibration analysis, the chatter problem can be solved, enabling much higher metal removal rates, better quality and longer tool life.

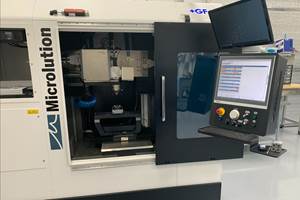

Read MoreWhere Micro-Laser Machining Is the Focus

A company that was once a consulting firm has become a successful micro-laser machine shop producing complex parts and features that most traditional CNC shops cannot machine.

Read MoreInside the Premium Machine Shop Making Fasteners

AMPG can’t help but take risks — its management doesn’t know how to run machines. But these risks have enabled it to become a runaway success in its market.

Read MoreHigh RPM Spindles: 5 Advantages for 5-axis CNC Machines

Explore five crucial ways equipping 5-axis CNC machines with Air Turbine Spindles® can achieve the speeds necessary to overcome manufacturing challenges.

Read MoreRead Next

Handle With Care

Micro-size drills and end mills don’t have to be difficult to use.

Read MoreApplying A High Speed Machining Discipline Without The Speed

In this shop, high speed machining makes sense at 4,000 rpm. While the disciplines the shop put in place made a new 15,000-rpm profiler dramatically more productive, high speed machining would have remained valuable even if the new machine never came. Acoording to a co-owner of this shop, high speed machining has no need for speed.

Read MoreCutting With A 0.001-Inch End Mill

JPL’s Space Instrument Shop does this routinely, but it takes some special equipment and some unusual procedures. Above all, it takes patience.

Read More