Share

Hwacheon Machinery America, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Takumi USA

Featured Content

View More

ECi Software Solutions, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

As 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing seeks new aerospace customers for its additive business, the company offers customers stability and supply chain streamlining through its machine shop.

In 2013, additive manufacturing (AM) was having its moment. The possibilities of the technology for industrial production were just then becoming apparent to manufacturing at large. Indeed, at that time, the view of AM was soaring from lofty media hype into a stratosphere of impossible promises. Bob Markley was having a moment of his own at that time. He had just finished a 10-year stretch as an engineer for an Indy 500 racing team before moving on to work for Rolls Royce and then General Motors, the latter of which was consolidating its Indiana workforce to Pontiac, Michigan. Unable to relocate his family from their Indiana home, the then-31-year-old Mr. Markley wrote up a business plan centered around AM — a technology he’d barely used, but one that appealed to the experimental engineering style he’d developed through racing.

Thus, 2013 proved to be the year that Mr. Markley went all-in on AM, launching Dimension Industrial 3D Printingrd3 in a 1,800-square-foot facility outside of Indianapolis. After opening for business, he quickly partnered with 3D Systems and brought in the company’s ProX 200 — a laser powder-bed fusion machine he still refers to today as his workhorse. Sustained financially by his original loan and a small but growing base of customers, Mr. Markley purchased a second ProX 200, followed by a 300 model and later a 320 that he beta tested for the company.

Again and again during two years of printing parts, turning knobs and experimenting with parameter controls, Mr. Markley’s experience with professional racing proved to be invaluable. As a beta user for the ProX 320, he felt the same freedom of experimentation as he did when reengineering components for high-performance race cars: Both were custom machines that required finely tuned calibration. The work pace was incredibly fast. Data interrogation — a critical tool for calibrating Indycars and metal 3D printers — took place in a compressed timeframe.

In early 2017, the world of auto racing gave back to Mr. Markley once more. An old friend from his former racing days called with the news that his racing team was shutting down. His crew was selling its CNC machine shop and everything in it.

He had called the right person. Mr. Markley bought nearly all of the equipment and hired a machinist.

Within a few months, 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing was packed not only with 3D printers but also a small fleet of CNC machines. Suddenly, the company had not only enough CNC equipment to finish machine the parts it produced additively, but also the capabilities of a standalone CNC job shop.

It’s this fact allows 3rd Dimension to operate in a way that not many AM service bureaus can. It also helps account for Mr. Markley’s willingness to say things that not many AM business owners say. “You can't just print for the sake of printing,” he says. When a job is suited not to additive but to machining instead — a common occurrence with work that customers offer him expecting it to be 3D printed — 3rd Dimension has the capability to produce it in the more efficient way. The alternative to additive thus makes the company a stronger additive service provider.

Several 3D printers are located at the back of 3rd Dimension 3D Printing’s expansive new shop. The new production metal AM machine from Additive Industries can be seen at right. The machine shop sits adjacent to this space.

Today, 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing resides in an expansive new building — 27,000 square feet with adjacent rooms for printing and machining. During a recent visit, I found that 3rd Dimension was quickly ramping up for additive production by investing in a powder-bed fusion metal additive system designed for scale production — a MetalFab1 system from Additive Industries. Yet, it’s the company’s fully developed machining capabilities that have created competitive advantages that go beyond post-processing 3D-printed parts.

Establishing a Process

3rd Dimension’s print production floor sits adjacent to the machine shop, and both are expansive, sprawling spaced. Mr. Markley and his colleagues custom designed 3rd Dimension with ESD floors, humidity control and dedicated space for metal powder handling. The room adjacent to the machine shop houses two large compressors that can each serve the shop’s needs if one goes down, and there is a dedicated transformer stationed outside that feeds 3rd Dimension enough electricity to power a small city.

3rd Dimension’s machine shop is large enough to house at least double its current inventory, which includes five Haas VMCs, two Mitsubishi Electric wire EDMs, a manual mill and lathe and an in-house vacuum heat treat furnace. Almost everything here was purchased wholesale in 2017 — four years after Mr. Markley founded the company as an additive manufacturing service bureau. Early on in 2013, there were a lot of unknowns and mistruths about AM. “One of them was that additive was going to replace everything,” Mr. Markley says, “and that you did not need any additional machining or support equipment. Of course, that’s a complete falsehood.”

The author and 3rd Dimension owner Bob Markley, talking in the machine shop of 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing.

From 2013 to 2017, Mr. Markley used his Indy racing connections to outsource 3rd Dimension’s machining operations, taking advantage of the excess capacity at his old racing crew’s machine shop to handle finishing operations on his 3D-printed parts. When the team began to wind down, Mr. Markley leased space from them. When they decided to sell the building, he offered to buy everything.

“We told them that we’ll go ahead and we'll buy the machine shop. We'll buy all the tooling. We'll buy everything you've got,” Mr. Markley says. “Until that point, we had limited capability in house — just one mill and one EDM. All of a sudden, we picked up all of that equipment, and in one swoop, we greatly increased our machining capacity and capability.”

So far, Mr. Markley says, the first priority for this equipment is to finish-machine the metal parts being printed in the next room. 3rd Dimension has already secured several aerospace customers, in part, because of the company’s ability to provide part traceability down to the print location and orientation on the build plate. In fact, Mr. Markley considers this to be critical to his overall production strategy — so much so that he’s applied that same level of traceability to a low-volume, high-value consumer product his company is producing on the ProX 320.

The Kallista Grid faucet, which 3rd Dimension prints out of 316 stainless steel powder in batches of six, is a study in negative space. It is the MC Escher drawing of bathroom hardware — a shape composed of a simple geometry manipulated into a seemingly impossible path. Where a typical faucet features a central spout for water to flow through, the Grid is composed of a rectangular, hollow metal frame that bends at 90-degree angles both horizontally and vertically. Water flows to the aerator via interior fluid channels printed within the rectangular frame — a design that can be realized only through 3D printing.

Three stages of production of the Kallista Grid faucet: newly printed, finish-machined and powder-coated.

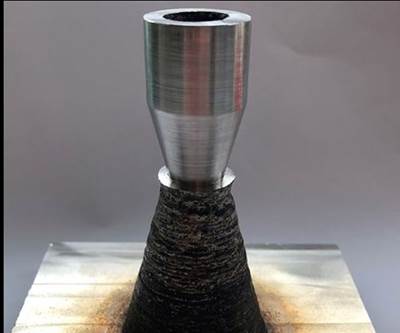

From printing to threading to finish machining, the faucets — which typically retail for $6,000 and won an international design award in 2018 — are produced almost entirely at 3rd Dimension. Everything except powder coating and assembly happens there. Because the company doesn’t have to outsource machining, the team can be aggressive while designing support structures — structures that will anchor the part firmly to the build plate and increase the chance of a successful print — and simply turn to milling or EDM for their removal. Mr. Markley’s team favors speed over surface finish during the printing process, then relies on his in-house machining capabilities to achieve the smooth aesthetic surfaces the part requires.

The complexity of the Grid faucet isn’t limited to its internal geometries and print variables. The number and orientation of the different faces that require machining is itself a challenge. But another advantage of having both printing and machining operations in-house includes the opportunity to print workholding structures onto the part that can be removed prior to finish machining.

All of these strategies and processes that 3rd Dimension has put in place for the Grid faucet — from part traceability to the design of workholding and support structures, to the print parameter sets to finish machining operations — clearly surpass the level of complexity involved with producing typical consumer products, even 3D-printed ones. But following this process for the Grid has allowed Mr. Markley and his team to prove out a systemized approach to the company’s production process. So, when the next prospective aerospace customer comes along, he can point to the Grid and say, “Here is how I manufactured faucets to a level of quality control and process documentation that faucets don't require. And I did that to show you what your production process will look like.”

Recession-Proof

Beyond offering supply chain integration and cost savings to customers, installing a machine shop next door to 3rd Dimension’s printing operations also provides an existential benefit to the company: the increased chance of long-term survival. Because what was true during the Great Recession will likely be true of the next downturn following it, perhaps the period we’re now in. That is, a sustained economic downturn will drag down many independent manufacturers that don’t have a diverse customer base and solid financials.

But the same period will also expose the degree to which additive manufacturing is recession-proof. Will the perception that additive manufacturing is “experimental” drive companies to retreat from it? Or will its potential for design consolidation and time and cost savings provide cover during an economic downturn?

For 3rd Dimension, its machine shop serves as a hedge against any potential retreat from industrial 3D printing. While its machine shop primarily serves 3rd Dimension’s additive business, it has a growing roster of parts it produces independently. Mr. Markley estimates that parts machined at 3rd Dimension will be on half of the cars at the next Indianapolis 500. In addition, 3rd Dimension is AS9100 and ISO 9001 certified, which has helped land it several aerospace contracts for low-production parts.

In this way, the machine shop carries value as a secondary revenue source for what is primarily an additively focused business. In the worst-case scenario — a major recession results in a retreat from additive manufacturing — it’s entirely possible that 3rd Dimension can keep its lights on via its machining work. And if the opposite occurs, the company can rightly tell potential customers that, yes, you can use us for additive manufacturing and we can provide your machined parts, too. Mr. Markley can also boast to potential customers that 3rd Dimension represents just one supplier in the customer’s system for additive parts. He can say that 3rd Dimension will take care of all of the necessary steps under one roof.

Or under various roofs, together.

When 3rd Dimension decides that a part should be produced additively, the company’s machining capacity serves as proof that additive is the right way to go.

In July of 2018, 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing partnered with Generation Growth Capital (GGC), a business investment fund focused on small-to-mid-sized manufacturing, service, and distribution businesses. The company’s portfolio includes high-end five-axis machine shops and other businesses that Markley says can assist with strategy, networking and establishing a platform to serve a broad array of customers. GGC helps handle the accounting and legal functions of 3rd Dimension, and, because of the other manufacturing businesses in GGC’s portfolio, essentially serves as a risk mitigator for 3rd Dimension’s customers.

GGC also bolsters Mr. Markley’s argument that if a part can be manufactured through machining, it should be. If a part requires complex five-axis machining, or if 3rd Dimension has a high-volume order for machined parts, the company can turn to a GGC partner to handle operations or take on its overflow. Suddenly, 3rd Dimension has enough machining capacity to allow Mr. Markley to feel like it’s his job — as a metal additive manufacturing production resource — to be prepared to find an alternative to additive for any potential job that comes to him.

Because in spite of all recent technological advances in 3D printing, additive is difficult. It requires process development. It's costly. All of these factors only increase the value of having machining capability. On the other hand, when 3rd Dimension decides that a part should be produced additively, the company’s machining capacity serves as proof that additive is the right way to go. Clearly, the company is ready to make money off of the part through machining when machining is the better option. Mr. Markley points to recent developments in commercial aviation as evidence supporting his strategy.

3rd Dimension is AS9100 and ISO 9001 certified, which has helped land it several aerospace contracts for low-production parts.

“This has been an eventful year in the aerospace sector, and one that has affected many suppliers,” he says. “And more broadly, we've seen the numbers about manufacturing in this country decline, and we’re seeing our aerospace customers trying to solidify their supply chain. That said, not everyone is willing to explore options with additive manufacturing. So it's nice to have both sides of the shop, if you will, in terms of stabilizing revenue.”

As 3rd Dimension seeks new aerospace customers for its additive business, Mr. Markley can make the case that his company offers stability through the machining work that it can be counted on to handle in addition to 3D printing. In other words, it can offer the right technological application for the right project.

“From a business perspective, the machine shop creates a couple of advantages,” he says. “One, it’s a diverse revenue line. It’s another source of revenue that helps us spread across various industries. And it allows us to use the right technology for each project. Additive is just like any other manufacturing process. You have to design for it, and you have to understand the rules and limitations. You wouldn't take something that was designed to be milled and try and turn it on a lathe. I see enough people out there that hit things with the additive hammer because that's the only tool they have. And it’s not always the right tool.”

Related Content

The Future of High Feed Milling in Modern Manufacturing

Achieve higher metal removal rates and enhanced predictability with ISCAR’s advanced high-feed milling tools — optimized for today’s competitive global market.

Read More4 Commonly Misapplied CNC Features

Misapplication of these important CNC features will result in wasted time, wasted or duplicated effort and/or wasted material.

Read More5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreOrthopedic Event Discusses Manufacturing Strategies

At the seminar, representatives from multiple companies discussed strategies for making orthopedic devices accurately and efficiently.

Read MoreRead Next

How Additive Manufacturing Is Like Five-Axis Machining

It’s not the similarities in the technologies, but in how they were and are being adopted.

Read MoreAdditive Manufacturing Belongs in a Machine Shop

A fourth-generation family machine shop integrates metal additive manufacturing as another production operation.

Read MoreCombining Additive and Subtractive Processes for Hybrid Machining

At this point, we are still learning how to combine the two to optimize hybrid manufacturing.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)