Additive Manufacturing with Sheet Lamination

No longer limited to paper, sheet lamination bonds sheets of material together to form an object. Companies are exploring the possibilities of this process.

Share

Figure 1: “Fit and form” prototype of the upright made with paper using sheet lamination in 1998.

The first class that I ever taught at Penn State University was the senior capstone design course in which students work on real-world design problems. During the course, students worked in Penn State’s Learning Factory, a hands-on facility that housed a variety of 3D printers for rapid prototyping, one of the early monikers for additive manufacturing (AM).

Keep in mind that this was in the late 1990s, so students had limited access to one of two material extrusion systems from Stratasys and one vat photopolymerization system from 3D Systems. The systems were very expensive to buy, and the materials were even more expensive, which made the third alternative even more attractive — a Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM) system from Helisys. Introduced to the market in the early 1990s, LOM was the first commercially available sheet lamination process for additive manufacturing. It was also one of the cheapest AM processes at the time because parts were made by actually gluing sheets of paper together, layer-by-layer.

If you think about it, the idea isn’t that crazy. Paper is about 0.1-mm thick, so the layer resolution is reasonable, and it was better than material extrusion systems on the market at that time. Paper is also easy to cut or score with a laser, so you did not need a high-power laser like you do to sinter plastic or fuse metal. Granted, you aren’t going to make many functional end-use parts out of paper, but for visual aids and “fit-and-form” prototypes, why not use a process that is cheap and relatively fast?

Fast forward three decades, and sheet lamination is no longer limited to paper. In fact, international standards organization ASTM defines the process as “an additive manufacturing process in which sheets of material are bonded to form an object.” Companies like Fabrisonic use ultrasonic welding to bond sheets of metal together to form a 3D object, giving them the flexibility to combine dissimilar materials to make functionally graded structures, create internal cooling channels in structures, or embed electronics or sensors into a part. Sheets are bonded together and then the shape is formed, exemplifying the “stack-then-cut” approach to sheet lamination.

Meanwhile, CAM-LEM Inc. (computer-aided manufacturing of laminated engineering materials) uses the sheet lamination process to form functional ceramic parts, specializing in microfluidic devices and applications. In this approach, individual layers are formed, then stacked and bonded together, exemplifying the “cut then stack” approach to sheet limitation. This reduces the amount of material needed to bond the layers together, but it limits the geometries that can be built because layers must be stackable on top of one another. For instance, it is difficult to make overhanging features with this approach to sheet lamination if there is nothing in the layer underneath to support the new layer and counteract gravity. Conversely, in the “stack then cut” approach, the material in the layer underneath helps fight gravity, but it must be accessible so that it can be removed after fabrication. In fact, this is one of the main drawbacks of the stack then cut approach, namely, the amount of postprocessing needed to chip away and remove the material that is not in the part.

Figure 2: “Fit, form, and functional” prototype of the upright made with titanium using powder bed fusion in 2013.

As you might guess, the material properties of parts made via sheet lamination depend on the bonding strength between layers. Material properties within a layer are typically the same as the feedstock used to make the part (i.e., you are not melting the material like you do with powder-bed fusion processes). This can give rise to some anisotropy in the vertical build direction, which might be a concern depending on the intended use of the part. In the case of my senior capstone design team, the intent for one of the teams was to rapidly prototype new upright designs and perform “fit and form” checks on the student Formula One race car that was being developed by a larger team of students (see Figure 1). Fast forward 15 years, and the same team can now use laser-based powder-bed fusion to additively manufacture functional prototypes to test “fit, form and function” (see Figure 2).

The technology has come a long way since I started teaching at Penn State, and while Helisys is no longer in operation, paper-based sheet lamination systems are still available from companies like Mcor. Not surprisingly, the advancements in paper-based sheet lamination mirror those in our 2D desktop printers — color is now a cost-effective option, allowing users to create photorealistic visual aids and full-color prototypes. This is why sheet lamination is finding new use in fields ranging from structural analysis, architecture and visual arts to life sciences, education and entertainment. Who knew that we could learn so much by gluing and stacking colored sheets of paper together?

Related Content

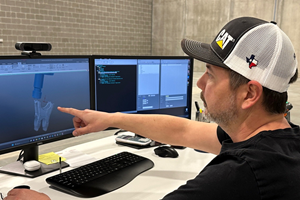

Digital Transparency in Machining Key to Multi-Site Additive Manufacturing

Cumberland Additive’s CNC programmer in Pennsylvania spends most of his time writing programs for machine tools in Texas.

Read More6 Trends in Additive Manufacturing Technology

IMTS 2024 features a larger Additive Manufacturing Pavilion than ever before, with veteran suppliers alongside startups and newcomers at the front of the West Building. As you browse these exhibitors, as well as booths found elsewhere at the show, keep an eye out for these trends in AM.

Read MoreChuck Jaws Achieve 77% Weight Reduction Through 3D Printing

Alpha Precision Group (APG) has developed an innovative workholding design for faster spindle speeds through sinter-based additive manufacturing.

Read MorePush-Button DED System Aims for Machine Shop Workflow in Metal Additive Manufacturing

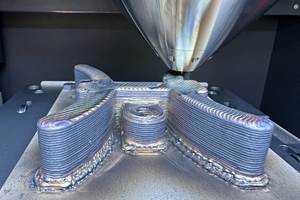

Meltio M600 metal 3D printer employs probing, quick-change workholding and wire material stock to permit production in coordination with CNC machines.

Read MoreRead Next

This Rocket Fuel Injector Is a Solid Part That Contains a Working Motor: The Cool Parts Show #1

Our new video series debuts with a look at a solid metal part made through additive manufacturing that was built with a motor embedded inside. The motor sealed within the part adjusts the rocket’s fuel mixture while the rocket is in flight.

Read MoreWhat Is Material Extrusion 3D Printing?

Material extrusion extrudes material through a nozzle and selectively deposits it layer-by-layer to form an object. After three decades of material advancements and a diverse array of start-ups and applications, the use cases for this technology are still going strong.

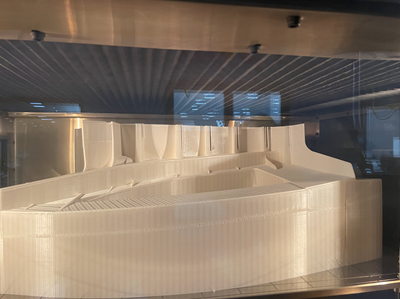

Read MoreCan 3D Printing Make a Better AM Build Plate?: The Cool Parts Show #5

Ultrasonic metal additive manufacturing was used to create a build plate aimed at making powder bed fusion more effective. This episode of The Cool Parts Show looks at a part by AM, for AM.

Read More