Share

Modern Machine Shop’s first podcast series — a documentary style, limited series called “Made in the USA” — launched today, and it begins, appropriately enough, with a story. It’s a story that covers decades and played out slowly, just beneath the surface for many of us. But it’s one that has affected our lives and livelihoods, our way of life and, for a time, unsettled Americans’ confidence in our economy.

Understanding the challenges that face American manufacturing today requires taking a close look at what happened to manufacturing employment at the beginning of this century. This episode examines the post-millennium collapse of American manufacturing jobs, and introduces the debate surrounding manufacturing productivity’s role in that decline during the early 2000s.

Listen to the first episode here, or visit your favorite podcast platform to subscribe to “Made in the USA.”

The following is a complete transcript for Episode 1 of the “Made in the USA” podcast.

In addition to the hosts, the commentary in this episode is provided by:

- Robert Atkinson, President, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation

- Mike DiMarino, President, Linda Tool

- Susan Houseman, Vice-President and Director of Research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

- Scott Smith, Group Leader, Intelligent Machine Tools, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT)

Scott Smith, Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Moving the jobs to China didn't kill the jobs. It just killed them in the US.

Susan Houseman, Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: It was really that one industry was giving us a misleading impression of what was going on in the rest of manufacturing.

Geno Atkins, Deking Screw: During those two weeks, he kept talking about our future. And I just like—I looked at him like “I told you, I'm leaving.” I mean, I didn't say that to him. I said, “No, I'm leaving.” And when it got to the last end of the two weeks, he said, and I don't think my dad ever said this to anybody ever in his life, he said, “Son, don't you know, I need you here.” It's an emotional time.

Daron Acemoglu, MIT: Japan, South Korea and Germany have increased their share of international trade in manufacturing. They have continued to make inroads in manufacturing growth. How did they do that?

Robert Atkinson, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation: Is it a problem that we lost a third of our manufacturing jobs in the 2000s, a higher rate of job loss than in the Great Depression of the ‘30s? Is that a problem? Well, the way that all of these pundits and economists and others have framed it, “No, no, no.”

Brent Donaldson, Modern Machine Shop: Almost anyone who runs for a political office in the United States, especially at the national level, talks about American manufacturing during the campaign.

Mike Pence, former Vice President of the United States: Manufacturing, and people who make things are the back bone of the American economy.

Brent Donaldson: And most of the time, at least over the past 20 years, those speeches include the idea of bringing back manufacturing.

Barrack Obama, former President of the United States: I don't want the next big job-creating discovery, the research and technology to be in Germany or China or Japan, I want it to be right here in the United States of America.

Brent Donaldson: Because there's something distinctly patriotic about the idea of bringing back manufacturing, of returning to a time when nearly all of the things that we use are made in the USA, the idea where anyone with a strong work ethic can land a job at a machine shop or a factory and get on the path to achieving the American dream.

Donald Trump, former President of the United States: Restoring American manufacturing will not only restore our wealth, it will restore our pride and pride in ourselves.

Joe Biden, President of the United States: I do not buy for one second, that the vitality of American manufacturing is a thing of the past.

Brent Donaldson: Of course, the reason why these speeches happen over and over again is because, at least during the past 20 years, that path has narrowed. In fact, between the years 2002 and 2010, 33% of manufacturing workers lost their jobs, a rate of loss exceeding that of the Great Depression.

So why did this happen? How realistic is it to talk about bringing back manufacturing or to convince younger generations to step into the manufacturing jobs that baby boomers are leaving in droves? Over the next six episodes, Made in the USA will explore these topics through conversations with manufacturing leaders and world-class economists, and shine a spotlight on the past, present and future of American manufacturing.

Welcome to Made in the USA. I'm Brent Donaldson.

Pete Zelinski, editor-in-chief, Modern Machine Shop: I'm Pete Zelinski. And over the course of the next six episodes, we are going to explore some of the biggest issues and ideas that shape our conversations about manufacturing: the decline in manufacturing jobs and how that decline has been steep in recent years; automation, what it means and what impact it has on the supply chain; the supply chain vulnerabilities that COVID-19 seemed to reveal; the retirement of the baby boomers from manufacturing; who's taking their place and how that transition is playing out; and the way forward from here.

Brent Donaldson: So, sort of a fundamental belief that we had going into this project was that the health of the US manufacturing sector impacts everyday people in critically important, but often hidden, ways. Over the course of the past several months, we've conducted dozens of interviews for this series that have confirmed that to be true, but also helped us understand some very complex challenges surrounding American manufacturing. I think a good place to start is to look at what happened to manufacturing employment at the beginning of this century.

Pete Zelinski: So let's begin with a story, a story covering decades, a story that played out in its full scope slowly, perhaps — just beneath our attention — but one that affected lives and livelihoods, affected our way of life and unsettled Americans confidence in our country and our economy. Listen:

Doug Woods, Association for Manufacturing Technology: If you dial back to World War Two, and even before that, whether it was what things we did with getting railroads put across the United States, leveraging steam engine capability, and whether you look at what Ford did with the assembly line and really mass-producing automobiles — if you look at what we did with the steel industry and look what we did in World War Two, we had a rapid ramp up of manufacturing of relatively complicated pieces of mechanized devices, you know, combinations of electronics and manufactured components and systems going into tanks and planes and, you know, vehicles being used in different parts of the transportation system. There's a lot of things that took place there that revolutionized where the United States’ position was as a leader in global manufacturing. And really that kind of still skated through the ‘50s and ‘60s and ‘70s, with us continuing to build on that certainly in the machine tool industry.

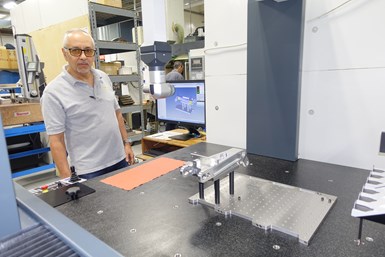

Pete Zelinski: Real quick, two things. First, the person speaking is Doug Woods, President of the Association for Manufacturing Technology, or AMT, which is a trade association representing builders and distributors of manufacturing technology: technology like machine tools. Second, quick definition, machine tools are machines — often big, often expensive — that precisely cut metal into exactly the shapes and the precise dimensions and finishes we need. The work they do — operations such as milling, drilling and grinding — is broadly called machining. When we mentioned machine tools and machining in this series, as we often will, we're talking about equipment at the foundation of our manufacturing economy. Because machine tools are the machines that make machines.

Brent Donaldson: We should probably note here that Pete and I write about these machining processes and technologies for a living. Pete is editor-in-chief of Modern Machine Shop, the country's leading trade magazine covering metalworking and machining, which I also write for as a senior editor.

So Doug Woods points out that throughout the 1950s, and 1960s, the United States was still the global leader in the machine tool industry. But when we began to lose that leadership, it had an immediate and consequential effect. For example, if a company like Boeing needs to build more airplanes, its suppliers that build the plane’s engine components need more machine tools to make those components. So if American companies that make the machine tools can't keep up with the demand, those suppliers are going to start looking overseas, which Doug says is exactly what happened.

Doug Woods: And what really seemed to happen as we got into the ‘70s and ‘80s, we got into kind of the period of leveraged buyouts and mergers and acquisitions, it was a lot about roll-ups. And what you saw was, the machine tool industry became kind of a victim of that process. And when I say a victim of the process, what ended up happening was a diametrical change from focusing on the core technology, focusing on innovation, focusing on innovating the next great product that solves a problem, to taking care of meeting a quarterly number, getting a return on the leveraged buyout, so the organization could be flipped again. And a lot of money was pulled out of the R&D areas, a lot of money was pulled away from innovation, and costs were being stripped out in order to make the multiples look good. A lot of the industry got devastated during that period, ‘70s and ‘80s, and into the early ‘90s, with that lack of focus.

Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT) Photo Credit: Doug Woods

And while that was all going on, of course, a lot of — now I’m particularly focused on the Asian sector of the world economy — a lot of those countries were actually doing huge investments, doing what we did, decades before in the ‘50s and ‘60s and ‘70s, they were now doing in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and ‘90s. They were investing in their manufacturing technology and machine tool technology. And when we were unable to — here in the U.S. — focus on delivering high-quality products that were easy to use, with a customer-centric focus, the Asian countries were coming in and filling that void.

Deliveries for some of our folks in the industry started going out to a year. I mean, you think about that now, it seems like insanity and you wouldn't believe it. But that was the situation at the time, so you had a reasonably high-price product that hadn't been really innovated as much as it should have been, with delivery times that were out to a year. People needed to have stuff in their factory to make new products, and so they turned to whatever place they could start to find solutions. That was kind of the start of the evolution of the Asian machine tool market getting a really big foothold into the US market, which was an enormous change for decades to come.

Pete Zelinski: I want to pause here. This is such a striking point. This seems important for really understanding our history.

We have an impression that producers of manufacturing equipment from outside the US — Asian machine tool builders — that they made their way in because of price, that they undercut US machine tools because they were cheap. Doug doesn't remember it that way. They made their way in because they were available. They came in not because of cost, but because of time. US manufacturers needed more machine tools to perform their manufacturing to make their equipment and products, and they couldn't wait on delivery times out to more than a year. They adapted, US manufacturing adapted, and part of the way we adapted was to import valuable equipment that wasn't made here, but was made somewhere else.

Brent Donaldson: Of course, there were other factors influencing the shift taking place during this time. The power and influence of unions was changing, investments in research and development were shrinking, tax reform in the 1980s eliminated a tax credit that US manufacturers received when they invested in new equipment. So during this period of time, really the entire trajectory changed.

Now let's skip ahead a bit. Here's Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation foundation, a Washington, DC think tank, talking about where we came to decades down the road in terms of US manufacturing jobs. Basically, the bottom dropped out.

Robert Atkinson: What happened to US manufacturing, really starting around the year 2000, was a very serious and long-term structural decline, largely due to competition from foreign nations and offshoring, a lot of that due to China. So many, many US manufacturing firms either closed down their operations — well, over 50,000 manufacturing firms went bankrupt in the 2000s. Either they closed down, or they shrank or they move just wholesale moved operations offshore. That hurt the overall US economy, it made the economy grow more slowly, it had significant negative impacts on particular kinds of workers, particularly non-college-educated workers who could make a reasonable living by working in manufacturing without having to have a college degree.

Pete Zelinski: Robert was the lead author of a report put together by the ITIF back in 2012 that included an amazing finding, showing how manufacturing job losses haven't just been ongoing, they have accelerated. The report states that between the years 2002 and 2010, the economy lost 13 times as many manufacturing jobs as it did the previous decade. On average, more than 1,200 manufacturing jobs were lost every day for 10 years, the net loss of manufacturing firms and facilities amounting to 66,000 manufacturing sites closed. In other words, says Robert’s report, on each day since the year 2000, for 10 years, America had on average 17 fewer factories, plants and machine shops than it had the previous day. Go to bed, wake up, you're in a day with 17 fewer places where manufacturing employees work — for a decade. Now we talked about how important it was that Asian manufacturing found an opportunity — got its start. There's much more to the story, because as Robert describes it, developments happen from there that penalized US manufacturers and inhibited our ability to innovate and get ahead.

Robert Atkinson: But the biggest change was really allowing China to join the WTO with very, very few guardrails. So, for example, there was no provision in there around currency manipulation. The Chinese manipulated their currency, they kept their value of their currency very low, which meant that imports from China to the US were essentially subsidized, if you will, and exports to China were taxed, that would be such an equivalent of that. That really hurt and there was no provision in the trade agreement to fight that. US administrations chose not to fight that.

Robert Atkinson, President, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. Photo Credit: Robert Atkinson

And then you had a whole set of other problems: massive subsidies. There was a very good book called Chinese Industrial Subsidies, and it just went through industry after industry — auto parts, steel, machinery, a whole set of industries where the Chinese government just lavished big subsidies on their manufacturers. Then they used those subsidies to import and dump products if you will, sell below cost to the US, putting out the business of US manufacturers. I’ll give you one example: in 2000, the United States had about 60 to 65% of the global market of solar panels. In other words, they were produced in the United States. And by the end of the decade, we had 5%, with China having 60%. Much of it was due to Chinese predation and subsidies that went unchallenged. And by the time they were challenged, the horse was out of the barn and our companies were dead.

Pete Zelinski: To recap, changes in ownership of manufacturing companies, and how we thought about the purpose and profitability of those companies, created an opening for imported manufacturing. The real cost differences hadn't come yet. But they were coming as a result of system-wide effects, bigger than any manufacturer, related to currencies and governments. And the story keeps going. As we'll see, the United States had to introduce its own system-wide response, as the effect of lost manufacturing jobs began to spread. And one consequence very likely, was the housing crash.

Robert Atkinson: The way to think about that, think about what was 1,100 jobs a day, think about that in terms of when those workers get laid off, or the company closes. The company now is buying--so not only does the workers’ purchasing power go way, way down, because they're unemployed, but the company, they don't buy as many supplies from suppliers, whether they're local or national. And so that gets cut back. So it's not just the manufacturers, its here in the community, it's the restaurants, it's the barber shops, it's the printing company that prints flyers for the company. And think about that from a — that's almost like a recession every day. And so it was this, it was this counterforce in the US economy that was making the economy contract every single day.

So, what happened? Well, what happened was, and this is the story that almost nobody understands, what happened was the Federal Reserve had to keep interest rates so low, for so long. Because every single day, we were having this mini-recession. It was like more people getting laid off, not spending money. So how do we deal with that? Well, we keep interest rates low, so that people you know, take out a loan to buy their car, otherwise, the economy would have sunk into a real recession. But it was keeping interest rates so low for so long, that was the single biggest factor in the housing bubble. And so the manufacturing crisis, I would argue, was a major cause of the housing bubble and the crash, and then all the damage that was done from that. So when you don't have your sort of — it's like when you do exercises, you know, they say, ‘Well, the first thing you got to work on is your core, do some planks.” When your core is fundamentally weak, it causes all of these ripple effects throughout the economy.

Brent Donaldson: Some pretty notable economists have argued that job losses in manufacturing are really no cause for concern, they're just a natural part of the development of our economy. Robert does not see it that way.

Robert Atkinson: Is it a problem that we lost a third of our manufacturing jobs in the 2000s, a higher rate of job loss than in the Great Depression of the ‘30s? Is that a problem? Well, the way that all of these pundits and economists and others have framed it, “No, no, no, it's just like agriculture.” You know, at one point 70% of Americans were farmers, and now it's 2% and American agriculture is even stronger? That's absolutely right. Absolutely right.

That's not at all what's going on in manufacturing. In other words, the story they're trying to advance is that all of these job losses — the 33% of manufacturing workers who lost their jobs — all of that, or 95% of that wasn't due to loss of competitiveness, and trade and unfair competition, it was due to just these manufacturing companies becoming so much more productive, that they needed fewer workers.

Brent Donaldson: Now, we've come to an entirely different part of this, and that's productivity. In other words, the notion that productivity and improvements in productivity explain how many manufacturing employees we ultimately need. So a definition of productivity is basically the amount of output you get for the amount you spend on labor. And there are two aspects of this, the cost of labor and what that labor can produce. Other economies, other nations have lower labor costs and lower wage rates than the United States. But labor cost isn't destiny. Here's someone who argues we could have made a different choice.

Scott Smith: I'm Dr. Scott Smith, and I'm the group leader for Machining and Machine Tool Research in the manufacturing demonstration facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Let's talk about the loss of the manufacturing jobs in the US, and I'm gonna argue that this was a conscious decision. This was — so in the timeframe that you talk about, this is when a lot of companies were relocating manufacturing from the US to China, right?

Scott Smith, Group Leader, Intelligent Machine Tools, Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Photo Credit: Scott Smith

And they were primarily doing that with an argument that the wage rate there was lower. I mean, this is an argument that is commonly made, you know, “we can't compete against those low wages, it's just natural,” and we were going to be a post-industrial society. So we would do all the design work here, and then the manufacturing would go to where the low labor rates were. I think this was this was a conscious decision. Now, I think that's completely wrong. I think we shouldn't have said, “we can't compete with low wages,” we should have said something like, “given the fact that there's a wage difference, how do we compete?” That's a completely different mindset.

Brent Donaldson: So can I stop you really quickly? When you say, a conscious decision — by who and what was the motivation and reasoning behind that?

Scott Smith: Well, I mean, it looks sort of obvious: if you're producing a product, and you're doing it in the US, and you require some labor, you have to pay a high labor rate. But you figure that you can just take the whole facility as it is, and move it to another country where everything will be the same, except that you'll pay those laborers less — then you'll make more money if you do that.

Right, that seems like an obvious thing, an obvious thought to have. If you're trying to maximize your profits, that seems like a rational thing to do. You have a duty to your shareholders to maximize the profitability of the company, so why wouldn't you do that? So that seems like a decision to me. But I think it's not correct.

It would be correct, if we had already figured out all the things that we could do to be competitive in manufacturing. But this discounts the value and the possibility of innovation to be competitive against low-wage countries. You know, if you look at the labor part of the cost of a product — there's lots of costs that go into a product, right, there's the cost of the raw material, there's the cost of the shipping, there's cost of advertising and so on. Labor is one component. But it's not just the wage that you have to pay, right? It's the product of the wage that you have to pay, and the time that it takes for you to make a thing.

So if you live in a high-wage country, and you want to maintain that wage difference, then what you have to do is get more productive. If you want to have a five-times-higher wage, then you have to have five-times-higher productivity to be even. Let's say that we're farmers, and we're going to cut wheat. One person with a sickle, bent over in the field, can clear something like a third of an acre a day, cut all the wheat in a third of an acre a day. Or if you give him a better tool, a five, which is the long-mold sickle, he can do something like an acre and a half a day. That's a low-wage country solution, right, the gathering of wheat as an activity for the whole town. You can't afford any special equipment, but you have all those people. So that's what they do.

In a high-wage country, you can't do that. You can't have all those people out there with sickles, you have to create a combine. And the combine combines the reaping and thrashing and the winnowing, all in one big machine. And now one person takes care of 1000s of acres all by themselves. And it's a way better job, they’ve got air conditioning and GPS and a stereo system in there. And sometimes farmers share the cost of the combine across multiple farms. That's competitive. Now it's true, people who were swinging sickles lost their jobs, but the wealth creation mechanism of the growing-of-wheat-state — if you don't compete, if you don't find a way to compete to be more productive, then not only do you lose that industry, but you lose the jobs anyway.

I'll try to be technical. I'll point out that in the same kind of timeframe that you're talking about, the US really lost jobs, but many other industrialized countries really didn't. You know, Germany has a lot more automation than the US does, but they didn't leave lose a third of their manufacturing jobs to China.

Brent Donaldson: Why?

Scott Smith: Yeah, that's a really good question. If it's just low wages, then surely that effect must have happened in Germany also, but that does not seem to be the case. The US almost completely lost the production of machine tools. Germany didn't, Japan didn't, Switzerland didn't. Those are not low-wage countries. Why didn't they lose their machine tool industry?

[Sponsorship break]

Brent Donaldson: Hardinge has been a pioneer in the metal and material cutting industry for more than 130 years. From super-precision lathes to innovative Hardinge workholding, Hardinge has been a longtime supporter of American manufacturing, and they are proud to announce the return of the manufacturing of their high-precision line of CNC turning and vertical machining center products to the United States in 2021. Hardinge is proudly partnering with Gossiger, Hartwig, and Morris Group Incorporated to distribute these products directly to its American customers. For more information visit hardinge.com. Hardinge! Made in the USA.

[Sponsorship break ends]

Brent Donaldson: Okay, so Scott makes a point that's just as relevant to agriculture as it is to manufacturing. If you don't compete, if you don't find a way to be more productive, then not only do you lose that industry, you lose the jobs anyway. Farmers who use combines don't need to employ as many workers as they once did, but they get to keep producing here in the United States — that production stays here.

Meanwhile, when it comes to manufacturing, there are still some very smart people who argue that the reason we lost so many manufacturing jobs in the early 2000s was because the United States became so much more productive. And therefore, we have overstated the loss of American jobs to foreign manufacturing, they say.

But there's an economist named Susan Houseman who looked into this question and she focused on a very specific, very narrow segment of the economic data related to manufacturing productivity. And what Houseman found was that the role that increased manufacturing productivity played in those manufacturing job losses was in fact, extremely small. Because very deep within the data, she found an outlier that was distorting the entire picture.

Susan Houseman: I am Susan Houseman, I am vice president and director of Research from the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. And I am an economist, really an academic economist, by training.

So when we adjust for changes in prices, when we adjust for inflation, lo and behold, it looks like for the last many decades, that manufacturing — I'll say many decades, at least up into the very early 2000s — it looked like manufacturing, real output growth was keeping pace with that in the economy overall.

Susan Houseman, Vice-President and Director of Research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

Because this was a bit of a puzzle: its share was falling, but lo and behold, when you addressed it for inflation, it looked like it was doing great. The way economists reconciled those two apparently conflicting pictures in the economic data was that the prices of manufactured goods were just not rising as quickly as those in services. And they would say, “Well, why is that?” Because labor productivity growth is just a lot higher in manufacturing, than it is in the services sector.

So they wrote this story that it was all about productivity. And it was assumed that if productivity growth was much higher in manufacturing than it was in the rest of the economy, and employment was falling — or the share at least was falling, it depends on the time period that you're looking at — then it was assumed that this was automation and that labor was simply being displaced, there was no problem with manufacturing. With output, growth and manufacturing, it was keeping pace with the rest of the economy, and we were doing great.

Of course, my point is that the statistics and data, which were typically published at the aggregate level for all of manufacturing, were masking a lot of weaknesses in most industries. And that one industry — namely the computer and electronics products industry — was really accounting for the apparent robust growth in both output and productivity in the economy. If you broke out what I’ll call for shorthand, “the computer industry,” really suddenly the output growth in the rest of manufacturing didn't look so good. And of course, there's still variation. But the computer industry was really an off the charts outlier.

Pete Zelinski: So what Susan was able to do was to strip away one narrow product sector from published labor statistics data. It was a product type whose impact and capabilities grew so much during this time that its seeming effect on the output of manufacturing completely distorted the real productivity numbers.

So you know, a manufacturer making a computer might make a product almost 10 times better than it did a few years ago, because of what has happened in computers. I'm oversimplifying here, but roughly, that effect has been buried all along in manufacturing productivity numbers. It distorted our perception of the overall health of manufacturing.

Brent Donaldson: It's easy to get lost in the weeds here, but here's one important point: statistical agencies were encouraged to adjust for improvements to quality in certain sectors, and especially in what we'll simply call “the computer industry.”

Adjusting for quality isn't something you would do to measure the change in price over time for a Big Mac, right? A Big Mac has been two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun forever — but you can't measure a Big Mac the same way that you measure a semiconductor. This year's semiconductor model might be twice as fast and have greater functionality than last year's model. But even if the price is the same between the old and new models, it's wrong from an economist’s standpoint to say that the price hasn't changed, because it's not the same product. Statistical agencies were encouraged to adjust for improvements in product quality. Susan says that doing this wasn't wrong, it just opened the door to a lot of wrong ways to interpret the data. That had huge consequences when it came to how we thought about the health of US manufacturing.

Susan Houseman: When I talked a bit earlier about how do we get this, what I’ll call “misperception,” about how well manufacturing overall was doing, it comes from the apparent much higher growth in productivity in the manufacturing sector than elsewhere in the economy. It turns out that most of the apparent higher growth, most of it comes from the computer industry. What's going on there — think about your microprocessors and semiconductors. Think about how rapid the technological improvements have been in that industry over the last several decades. You know, Moore's Law, they’re just growing at an exponential rate in terms of their capabilities.

It was really that one industry which was giving us a misleading impression of what was going on in the rest of manufacturing. And we see that it's no longer obvious what's causing the relative and, of course, in the early 2000s, absolute declines in employment. I suggested stripping out the computer industry from our aggregate numbers, and it was staggering. I hadn't appreciated how much the computer industry had been driving the growth in manufacturing, output and productivity.

Pete Zelinski: We've heard from people who represent, study and think about manufacturing, but let's bring this home now. Here's Mike DiMarino. He's the owner of Linda Tool, a metal part producer and machine shop located in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn. Mike agrees that much of the predicament the US found itself in 20 years ago was self-inflicted.

Mike DiMarino, Linda Tool: My name is Mike DiMarino, I'm the owner of Linda Tool. We're a precision component manufacturer located in Brooklyn, New York. We've been in business 60+ years. Basically, politicians, they'll always say what you want to hear, and then do what they want to do. That's been American politics forever, unfortunately.

We really are run by financial engineers in this country. Why?

Mike DiMarino, President, Linda Tool. Photo Credit: Modern Machine Shop

Greed. I mean, simple, simple greed. Yeah, you know, they stepped over a dollar to pick up a dime. So people used to buy stock in a company because of their integrity, because of what they could do. Now they buy it based on the growth that it can have in share price and the yield they can get out of it.

I mean, everybody wants to make money, let's face it. That's what I tell everybody all the time. “So what do you do?” “I do the same thing as you do.” “No you don't, I bake bread!” “No, at the end of the day, what do you want to make? You want to make money? I want to make money too. I just chose to do it this way. You chose to bake a loaf of bread.” We all have the same product at the end of the day.

Brent Donaldson: Okay, so Mike is great to end on because his perspective lines up with what Doug Woods was saying at the beginning. Treating manufacturing companies as financial instruments, instead of valuing them for what they make, is exactly what set us on a certain path. Let's say it's a path that we didn't have to take.

The other thing we heard a lot in this episode about is how profit motives helped drive offshoring and acquisitions throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, which set us up for the 2000s. I think it's interesting that DeMarino sort of turns the argument around and says, “Well, at the end of the day, we all want to make money.” Because that's also correct. It's easy to look back and cast judgment on maybe short-sighted decisions, but with everything that's happened since then, have we learned our lesson? Have we changed our base instinct or our motivations? I think those are still open questions. Pete, what are your thoughts?

Pete Zelinski: I have a few thoughts. We can't accept that productivity caused job losses. It doesn't add up, and it lets us off the hook from facing and addressing what we need to do.

We talked about machine tools. That is what I've spent my career mostly studying, and the biggest productivity change in machine tools — maybe the biggest transformation of the technology of manufacturing — came with the arrival of CNC, or computer numerically controlled, machine tools, automated programmable machine tools where these machines used to be driven manually or mechanically. And if this automation caused job losses, we'd see the most job losses as CNC technology was coming online. But the wave of CNC adoption was in the 80s and 90s, where the steep job decline didn't begin until after 2000.

Also, there's the agriculture analogy. We heard it briefly in this episode: agriculture used to employ more than half the US workforce, now like 2%. Won't manufacturing go the same way? No. The answer's no, there are differences. Agriculture is prone to spoilage. It has a shelf life. Also, there's finite land area and a finite appetite — literally — for agricultural produce. Other sectors don't work that way. Think of data advances. When we became more productive about how much data we could generate and transmit, we changed our desire for data. We created social media, streaming, much more use for data.

I say all that because manufacturing could be the same: with more productivity we’ll realize new possibilities — ones I'm not smart enough to imagine — for manufactured items and what they'll do for us. I come back to what Doug Woods said: foreign manufacturers didn't come in because of cost, they found their way in because of time. We settled for not producing fast enough.

Productivity is not the cause of what we've seen, as Susan Houseman taught us. We haven't even had as much productivity gain in manufacturing as we've been thinking we do. But productivity is the answer, or part of the answer.

Choices got us here. Choices can get us back. There's a path, just like you said, and the path involves productivity. Relaxing on productivity, or not seeing the need for productivity, set the stage for job losses, and emphasizing productivity now can help set us on a better course.

Brent Donaldson: Made in the USA is a production of Modern Machine Shop and published by Gardner Business Media. The series is written and produced by Peter Zelinski and by me; I also edit the show. The podcast was recorded at the historic Herzog studio, home of the nonprofit Cincinnati USA Music Heritage Foundation. Our outro theme song is by The Hiders. You can find more information about Made in the USA at MMSonline.com/madeintheUSApodcast.

If you enjoyed this episode, please go tap that fifth star in the Apple Podcast review. If you have comments or questions, email us at MadeintheUSA@gardenerweb.com. Up next we dive into a topic we hinted at when we talk about productivity. Does automation strengthen manufacturing? Does automation compete with manufacturing jobs? We'll find out on the next episode of Made in the USA.

Related Content

Which Approach to Automation Fits Your CNC Machine Tool?

Choosing the right automation to pair with a CNC machine tool cell means weighing various factors, as this fabrication business has learned well.

Read More4 Steps to a Cobot Culture: How Thyssenkrupp Bilstein Has Answered Staffing Shortages With Economical Automation

Safe, economical automation using collaborative robots can transform a manufacturing facility and overcome staffing shortfalls, but it takes additional investment and a systemized approach to automation in order to realize this change.

Read MoreSame Headcount, Double the Sales: Successful Job Shop Automation

Doubling sales requires more than just robots. Pro Products’ staff works in tandem with robots, performing inspection and other value-added activities.

Read More3 Ways Artificial Intelligence Will Revolutionize Machine Shops

AI will become a tool to increase productivity in the same way that robotics has.

Read MoreRead Next

Setting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More