Profitable Additive Manufacturing Is Not an Oxymoron

How a kangaroo, a chest implant and the cost of argon prompted a question that led to the subject of this month’s column.

Share

Takumi USA

Featured Content

View More

While we have all gotten used to working virtually on Zoom and other video conferencing platforms during the pandemic, we have lost the opportunity for the spontaneous conversations that occur before and after meetings, in hallways, or around the coffee maker in the office or at a conference. Fortunately, a failed Zoom seminar happened to leave three of us alone on a Zoom call — and serendipity struck.

Thanks to the power of Zoom, I have been able to travel the world (virtually) and visit a different country each week as part of the “Additive Around the World” seminar series that I launched at Penn State this Spring. It has been great to “teleport” to different countries without the jet lag and air travel, but it is still hard to have a casual conversation with a seminar speaker when there are dozens of other folks listening.

When it was time to travel “down under” to visit with Alex Kingsbury (@AdditiveAlex on Twitter), the Additive Manufacturing (AM) Industry Fellow at The Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) in Australia, we ended up recording her seminar and then holding an “office hour” for Q&A due to the 14-hour time difference.

In order to make AM profitable, focus on the details and scan the horizon constantly — much like trying to find the kangaroos in the background of a Zoom meeting. Image Credit: Alex Kingsbury

While we tried to spot the kangaroos on the hillside behind Kingsbury as she drank her coffee, we realized that none of the students in the course showed up for the Q&A. Looking back, why would they? Rarely did they attend office hours in real life. Why did I expect virtual office hours to be any different? I mean, how often do you get to meet someone that helped additively manufacture a titanium chest implant for a cancer patient? I thought that would surely draw a few students to the Q&A.

Luckily, Kingsbury’s good friend SJ Jones (@Inconelle on Twitter) joined to support her, and the three of us ended up chatting on Zoom for nearly an hour. We talked about everything from the changing landscape of medical device regulation in Australia to the exorbitant rate at which argon is consumed in some laser powder bed fusion systems to the latest #AMWTF build failure that I shared from my AM lab at Penn State.

After we grew tired of trying to one-up each other with our worst build failure, someone jokingly asked: How in the world does anyone make any money with AM? Eventually, the three of us began wondering if the phrase “profitable AM” was an oxymoron. It sounds funny at first, but it led to the serious question of how anyone makes money with AM. One build failure in a laser powder bed fusion system can easily cost tens of thousands of dollars.

As Kingsbury shared her story about the chest implant, I learned that, many times, the costs can simply be passed directly onto the patient for custom implants, for instance, based on the way medical devices are classified in Australia. As the regulatory landscape shifts, however, so too do the billing and charge rates, and thresholds are established for reimbursable costs. This creates a ceiling on what things can cost if an AM device has to make a profit, but companies like Stryker have figured it out. It has one of the largest installed bases of laser powder bed fusion systems in Cork, Ireland, where it additively manufactures titanium hip implants by the tens of thousands each year. Meanwhile, Invisalign makes hundreds of thousands of custom dental aligners every day with 3D printing technology; it can be done.

Interestingly, AM service bureaus are also figuring it out; just take the recent acquisition of Morf3D by Nikon as an example. Actually, my first meeting with Ivan Madera was rather serendipitous as we both ended up sitting on a bench in a shopping mall after his 3D printing presentation at a conference. We discussed the challenges he was facing getting the fire marshal to approve storing pyrophoric materials in the new start-up he was launching, and now, six years later, he and his team have shown that AM can be profitable.

As the joking subsided, our conversation turned serious. “Successful AM companies are the ones focusing not on the profit made per build, but on how AM adds value to the overall product bottom line in terms of efficiency gains, new material combinations, advanced thermal designs and the like,” Jones pointed out. Of course, if you follow her Twitter feed, you’ll sympathize with her daily struggles, many of which she attributes to the lack of Design for AM (DfAM) knowledge in the industry.

For Kingsbury, who coincidentally began her AM journey modeling the costs of an electron beam powder bed fusion system, it came down to prototyping versus manufacturing. “AM can be profitable, but it tends not to work so well in the realm of one-offs, especially when they are designed by those less familiar with the particularities DfAM,” Kingsbury explained. I couldn’t agree more. She summed it up by noting that AM can be profitable when it scales. “The development phase is ironed out, build failure points have been addressed, and importantly, everything from the layout to the post-processing can be optimized,” Kingsbury added.

To be profitable, AM can’t be a “one and done.” It doesn’t work to simply pick a part and additively manufacture it. Any knowledge gained must be transferred to the next design, the next build, the next material you use — not jettisoned when it doesn’t work right the first time. Of course, smart companies do that, and they find ways to keep serendipity alive. Good thing, because you never know what conversations are going to end up making AM profitable.

Related Content

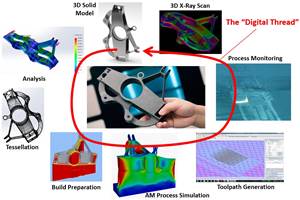

Go Digital: How to Succeed in the Fourth Industrial Revolution With Additive Manufacturing

The digitalization of manufacturing is set to transform production and global supply chains as we know them, and additive manufacturing has been leading the way in many industries.

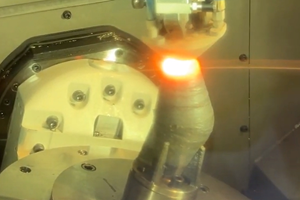

Read MoreAdditive/Subtractive Hybrid CNC Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Read MoreIn Moldmaking, Mantle Process Addresses Lead Time and Talent Pool

A new process delivered through what looks like a standard machining center promises to streamline machining of injection mold cores and cavities and even answer the declining availability of toolmakers.

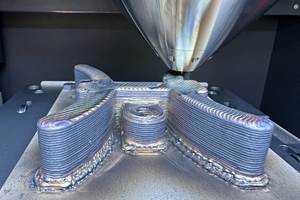

Read MorePush-Button DED System Aims for Machine Shop Workflow in Metal Additive Manufacturing

Meltio M600 metal 3D printer employs probing, quick-change workholding and wire material stock to permit production in coordination with CNC machines.

Read MoreRead Next

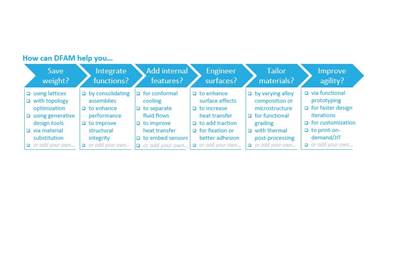

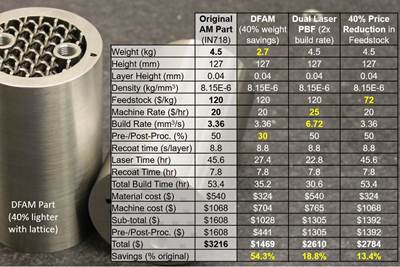

Finding Value with Design for Additive Manufacturing

Six questions can help you find value as you apply DFAM.

Read MoreThe Value of Design for Additive Manufacturing (DFAM)

Design is the “value multiplier” when it comes to additive manufacturing.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.png;maxWidth=150)