Production Without Paper

Giving operators electronic access to job information was the first step. Letting operators electronically refine that information came next.

Share

Hwacheon Machinery America, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Autodesk, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Takumi USA

Featured Content

View MoreThey don't call it "hard copy" for nothing. Relying on paper can make the manufacturing process inflexible.

And instrument maker Spectra Precision long ago identified the reasons why.

At the company's Dayton, Ohio, headquarters and manufacturing facility, some uses of paper add small amounts of cost and delay to the process. Case in point: At present, it takes a designated document manager to ensure that manufacturing personnel from all relevant parts of the organization have signed off on documents related to machining any new part number, per the company's ISO 9000 requirements.

But other uses of paper carry the potential for far greater loss. When the machining process for an existing part number is changed, for example, all of the hard-copy instruction sheets affected by the change have to be tracked down and revised. Miss a revision, and the operator might unknowingly work from an outdated sheet, causing parts to be scrapped.

Costs like these illustrate why Spectra Precision has long been interested in moving to a system for communicating manufacturing information that uses paper as little as possible. Eliminating paper has little to do with saving trees. Instead, it has everything to do with realizing a more flexible, more responsive process where new parts and new improvements can be implemented with minimal chance of error or delay.

In fact, the company once contracted with an outside firm to try to develop such a system. The goal was to manage NC program files and all process-related documents by means of a single paperless infrastructure. But that consultation ultimately failed to produce a custom-engineered solution that Spectra was satisfied with.

Flash forward to 2000, however, and the picture changes. This year, the company did achieve a system that meets many of its paperless requirements . . . and it achieved that system not by building it from scratch, but instead by assembling it mostly from off-the-shelf, Windows-based components. At the heart of this system is Windows-based DNC software that Spectra not only uses to manage NC files, but also uses in conjunction with basic office software to communicate other manufacturing information, as well.

And soon that communication will move in two directions. Spectra's short experience with the system has already shown the company how to make the system more effective. By building on functionality of the DNC software, the company will soon realize a mechanism by which operators can submit process improvements electronically, allowing those improvements to be evaluated and implemented more efficiently than ever before.

The pieces are not yet in place for this two-way system, but Spectra has clearly identified what all of those pieces are. And the improved system may already have been implemented by the time these words reach you. When it is, Spectra's shopfloor network will no longer be just a tool for paperless information access...it will be a tool for paperless collaboration, as well.

Getting There

A few numbers illustrate the scope of information management this collaboration requires. Spectra's approximately 60 machine tool operators work through various shifts at 39 CNC machines, producing an ever-changing array of about 1,900 part numbers for the company's broad line of laser-based leveling products.

And according to company manufacturing engineer Charles "Shorty" Swartz, at least one other number proved important in the development of the new paperless system. That number is 2000, the year it was implemented. The company's previous DNC system was not Y2K compliant, and Spectra had the distinction of being the last remaining user of that system running it on a UNIX platform. Accordingly, that version of the software would not be updated...so Spectra found itself needing to select and install an entirely new package for DNC.

The fact that the company would have to start from scratch gave it the opportunity to take a fresh look at the DNC options available today. The system the company finally chose came from CNC Engineering of Enfield, Connecticut. Spectra bought enough seats of the CNC Engineering software to outfit 34 stations on the shop floor. (Some stations link to more than one CNC.)

The company chose a Windows-based system because this compatibility meant that a generic PC at every station was essentially the only new hardware the system required. That same PC could then be used to give operators access to other information on the network beyond just NC programs. For example, two instruction sheets essential to every job—sheets for setup and inspection—already existed as electronic files. They were Microsoft Word documents. And with PCs running Windows on the shop floor, operators could begin accessing the latest versions of these sheets directly off the network, instead of following the more risky procedure of letting dated hard-copy versions circulate through the shop.

In fact, the usefulness of an open, PC-based solution was clear to the company early in the evaluation process. Even before the company decided which DNC system to buy, Mr. Swartz had already begun to organize the Word documents into job-specific folders for the benefit of the operators on the shop floor.

He did more than this, too. He had part prints and entire machine manuals scanned in, so this information could also be stored electronically. The DNC software made it practical to share all of these files across the network, because a security feature of the software allows documents like these to be viewed and printed at the machine tool, but not modified. Thanks to this feature, practical paperless communication with the shop floor was achieved.

But after using the software for a short time, Mr. Swartz and others in the company came to want more. They came to see that—for their particular process—offering the operator some freedom to initiate changes electronically was potentially much more valuable.

Obviously, access has to be limited. Sixty or so operators is far, far too many people to have authority to revise crucial documents. For consistency's sake, the authority to make revisions has to be limited to one person, or to a small group that works together closely.

However, at Spectra, influence over the process is not limited. Quite the opposite is true. Spectra's culture is one that encourages process-related input from the shopfloor personnel . . . based on the philosophy that if a speed or feed rate is too slow, or if a different tool or different tool path could make the cut better, then perhaps only the person at the machine tool will see this clearly.

As a result, machining processes are often refined because of operator feedback. And as part of this refinement, the process documents—setup sheets in particular—often change to reflect changes in the NC program.

The problem was, even with the new paperless system, Spectra found itself limited to the previous paper-driven process for making changes to these documents. If a change to the NC code necessitated a change to that job's setup sheet, then Mr. Swartz would have to make sure he obtained a marked-up version of that sheet, so he could review the changes and enter them himself into the Word document.

This was a cumbersome process for Spectra because revisions here come so frequently. It's not uncommon for Mr. Swartz to see several proposed program changes per day. That's why he hoped for a more streamlined system.

And he was encouraged to believe this streamlining could be achieved, because the authors of the DNC software had already found a way to streamline exactly the same process as it applied to NC program revision.

The DNC software—its brand name is "Focal Point"—includes an administrative function that lets the operator receiving a program file make edits directly to the NC code . . . but only provisionally. The proposed revisions then go to a designated administrator such as Mr. Swartz. Only if the administrator approves does Focal Point overwrite the original program. And even then, the software saves the previous version of the program to an archive file so the changes can later be undone.

Spectra certainly is not unique in the simple fact that it uses Word documents to provide supplemental information to operators about each job. However, Spectra does stand out for the volume of such documents it must maintain, and the frequency with which one or another set of documents is revised to reflect an improvement in the machining process. So the company asked, Could the same functionality that controls NC file revision also be applied to other kinds of documents?

CNC Engineering said it could indeed. To make the system more effective for Spectra's needs, the software developer offered to modify Spectra's version to permit paperless collaboration not just for NC programs, but also for the documents operators consult to run the programs correctly.

e-Approval

For NC files, the software's administration feature works like this: When an operator makes a change to an NC program, a copy of that file is sent to Mr. Swartz with the changes highlighted. He opens this copy, and the changed version of the program is displayed on his screen side-by-side with the original. This lets him quickly evaluate each change. To accept the revised version, he simply mouse-clicks on a button. The revision becomes the new, current version of the program.

Mr. Swartz says this system allows him to check and approve many types of proposed NC program changes about as easily as checking his e-mail. In fact, when he returns to his desk after being away from it for a time, he often finds multiple proposed revisions waiting for him in his DNC "in-box." The revisions he can't approve quickly are the ones that require changes in related documents.

The modified version of the DNC software will change that. It will allow operators not only to view and print supporting files, but also to red-line them, for sending proposed revisions back to Mr. Swartz electronically. The shop is now evaluating which red-lining software it will use for this purpose. When both the revised DNC software and the red-lining software are in place, Mr. Swartz will be able to review and approve almost all proposed changes quickly, not just the ones that only affect the NC code.

Beyond Production

Spectra expects to have that modified version of the software in place within the coming weeks (as of this writing, that is). However, beyond that software, the company is already taking additional steps to make its network an even better communication tool.

One of these steps is very simple. It involves a document called "operator notes" that Mr. Swartz has added to every job file. This Word document is one that operators can edit, whenever they want. The purpose of the document is to give operators a ready and consistent place to communicate status information, as well as tips, related to that particular job. Encouraging operators to communicate this way instead of using slips of paper near the machine is one more step toward achieving a completely paperless system.

And a much bigger step will come when other parts of the organization go paperless, too.

The company's success at assembling Windows-based components to build a system for the shop floor has encouraged it to expand that paperless communication even further. The next step, says Mr. Swartz, is to move the system for approving jobs that have not yet reached the shop floor into the electronic realm, as well.

The simple need for a signature has prevented such a move in the past. ISO 9000 procedures require the various approvals for each new machining process to be indicated with a signature. And historically, there has been no practical way to obtain this signature except through the medium of pen-and-paper.

Today that's no longer true. Anyone who has used a credit card at a department store recently has probably seen the electronic stylus-and-pad used to enter signatures into a computer.

The same technology can be applied to manufacturing, Mr. Swartz says. He adds that he has already begun evaluating software tools for signature management.

Related Content

The Power of Practical Demonstrations and Projects

Practical work has served Bridgerland Technical College both in preparing its current students for manufacturing jobs and in appealing to new generations of potential machinists.

Read MoreHow to Mitigate Chatter to Boost Machining Rates

There are usually better solutions to chatter than just reducing the feed rate. Through vibration analysis, the chatter problem can be solved, enabling much higher metal removal rates, better quality and longer tool life.

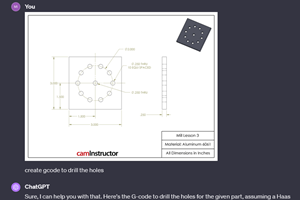

Read MoreCan ChatGPT Create Usable G-Code Programs?

Since its debut in late 2022, ChatGPT has been used in many situations, from writing stories to writing code, including G-code. But is it useful to shops? We asked a CAM expert for his thoughts.

Read MoreCutting Part Programming Times Through AI

CAM Assist cuts repetition from part programming — early users say it cuts tribal knowledge and could be a useful tool for training new programmers.

Read MoreRead Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read More

.jpg;width=860)

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)