Mainstream Technology Keeps Shop On Track

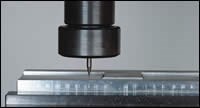

In its toolroom, Branchline Trains takes a practical approach to machining with end mills as small as 0.005 inch in diameter.

Share

Machining complex, contoured pockets efficiently and to tight tolerances is common in metalworking these days. It’s a challenge that Sam Krutt, the production manager at Branchline Trains, faces frequently. He is responsible for programming and operating his company’s machine tools. Like others in his position, he is concerned about maximizing metal removal rates, protecting the life of his cutting tools and achieving fine surface finishes that reduce or eliminate secondary operations. Like his counterparts elsewhere, Mr. Krutt shares a strong interest in meeting this challenge with capable, mainstream technology—machine tools, cutters and CAM software that are not “nichey” or highly specialized.

What makes Mr. Krutt’s challenge unusual, however, is that his contoured pockets are often so small that they routinely require end mills only 0.005 inch in diameter. These pockets represent details in the plastic injection molds that Branchline Trains builds to produce its line of high-quality HO-scale (1:87) model railroad products. “The railroad car models themselves can be 12 inches long, but some of the smaller attributes found on them are very small,” he says. “We’re dealing with piping that’s 0.015 inch in diameter and ladder rungs and grab handles on the sides of the rail cars that probably aren’t more than 0.020 inch thick. It’s very fine detail work.”

Mr. Krutt is able to machine mold features of this size without exotic equipment. “I have a top-quality machining center, the latest version of my CAM software and a local cutting tool manufacturer that can produce specials for me when I need them,” he says, “but nothing that most shops would consider extraordinary or out of reach.”

Mr. Krutt considers the shop’s CAM software the best example of what he means. Branchline Trains has always used Mastercam from CNC Software Inc. (Tolland, Connecticut), a PC-based programming system. Last year, he installed the latest release of this software, Mastercam X. Many of the standard features, both old and new, in this release lend themselves to his special applications.

“Because I work with small-diameter end mills, high speed machining techniques are very important. For example, I need the smoothest possible motion when running at 40,000 rpm with such small tools. Having options for choosing tool paths that control how the cutter enters and exits the cut avoids tool breakage and reduces cycle time. Other features such as solid model verification allow me to run the machine overnight,” he explains.

This software also enables Mr. Krutt to do some basic CAD design directly in the CAM package. This is a significant time-saver because he does his own CAD design and CAM programming.

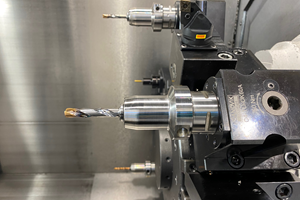

The machining center is an MX45 VAE from Okuma (Charlotte, North Carolina) that is equipped with an auxiliary 40,000-rpm spindle from NSK America (Schaumburg, Illinois). “This 10-hp machine has glass scales for accuracy and linear ways for the rigidity that I need when cutting with delicate tools,” says Mr. Krutt.

For the small diameter end mills, he turns to Microcut Inc. (South Easton, Massachusetts). This manufacturer has a line of two- and four-flute end mills in sizes as small as 0.002 inch, many of which have a diamond coating that works well in the aluminum alloys that Branchline Trains uses for its molds.

Getting the desired results is directly linked to the company’s success in the marketplace. Among dedicated model railroad enthusiasts, Branchline Trains has earned a reputation for highly detailed, prototypically authentic scale models of railroad rolling stock such as cars for moving freight, refrigerated produce and passengers. These products appeal to both the purist “rivet-counters” and the budget-conscious hobbyists. In a time when fewer and fewer U.S.-based model railroad manufacturers are able to sustain stateside production, Branchline Trains continues to do most of its manufacturing in its East Hartford, Connecticut, facilities. Efficient machining of mold components in-house is essential to keeping quality control tight and the operations profitable.

Evolving As A Manufacturer

Branchline Trains has been producing high-quality HO-scale model railroad products since 1991. In the beginning, the company purchased undecorated cars and then had them painted and lettered to its specifications by outside contractors.

It wasn’t long before the owners decided to set up their own printing facility so they could bring the process under closer control. This allowed them to keep a better eye on the quality of the finished products and offer a more diverse range than what was previously possible. As its line of custom-decorated cars grew, the company became known for superior, highly accurate print jobs. It moved production facilities to a building adjacent to the main yard of the Connecticut Southern Railroad.

In 1997, the company began development work on the first of its own line of HO-scale freight cars. Marketed as the Branchline-Blueprint Series, these cars were designed to set new detail standards for a freight-car kit.

To develop its own line of products, Branchline Trains had to have its own production capabilities. Therefore, for manufacturing, the company acquired three plastic injection molding machines, a ram electrical discharge machine to do mold and repair work, the three-axis vertical machining center and a Bridgeport knee mill. The company now has about 20 employees developing and producing products in a 12,000-square-foot facility. All of Branchline Trains’ molding, painting, decorating and product development is done in its Connecticut facility. Injection molding production runs are anywhere from 50,000 pieces, if it’s a very popular kit, to as low as 5,000 parts per year.

These highly detailed products start out with a prototype blueprint. “We do study a full-scale boxcar and make decisions on how we are going to approach its assembly,” says Mr. Krutt. “One of the features that makes our kits stand out in the market is that we design our boxcar kits in a modular fashion to simplify the process from a machining, molding and decorating standpoint. Also, when you create something such as a boxcar, you’re creating a mold that, in some cases, has to be formed with a slide mechanism to produce the four sides of the box.” Isolating the components allows them to be machined as a flat surface, Mr. Krutt says. He continues, “When we create inserts for the mold, they are much easier to work with if we don’t have to create all four detail aspects of the boxcar sides. What we’ll do is create side inserts for the boxcar with the appropriate lines, rivet and latch detail, or holes if there are other mounted components. Then we’ll create another set of molds for the two ends. We’ll produce additional molds that create roofs, underframe components and other detail parts.”

Getting A Handle On Toolpath Strategies

The image in Figure 1 exemplifies the detailed machining required at Branchline Trains. The geometry represents the handle and latch for securing a door on a railroad boxcar (specifically, a type of car widely used on the Pennsylvania Railroad and other lines that are popular subjects for American model railroad layouts). Although the handle on the real boxcar, as shown in Figure 2, measures 20 inches long and 1.5 inches wide, its counterpart on scale model must be exactly 87 times smaller. (HO scale, the most popular size of model railroad products, is 3.5 mm to the foot, an oddball proportion that is close to 1:87.) This means that the handle on the model will be 0.23 inch long and only 0.017 inch across. “The hobbyists we cater to expect details such as that handle and latch to be rendered perfectly on the model,” says Bill Schneider, who shares top management of the company with Mr. Krutt. Mr. Schneider handles product research and marketing, so he knows what the customer wants. “This level of detail and accuracy makes our models distinctive and is sought after by the discerning modeler.”

Of course, these latch and handle details become contoured pockets in the mold cavity. The pocket must also have the appropriate draft angle so that the molded product can be released when the mold opens.

Here is how Mr. Krutt approaches this as a machining project. He starts with CAD, working in either SolidWorks (Concord, Massachusetts) or the design function in Mastercam. A design file created in SolidWorks can be opened directly into the CAM software, so there is no disadvantage to using the CAD software for more complex designs. “If I can start with a 2D sketch and simply add depth, working in Mastercam is clearly the simplest and fastest way to go,” he says.

Creating tool paths is where things become interesting. On one hand, Mr. Krutt has found that a programmer has to think about the same issues and concerns whether the tool path is for a 0.5-inch end mill machining the forging die to produce the real-world handle or a tool path for a 0.005-inch end mill machining the mold for the HO-scale model. Mr. Krutt explains: “I have to consider the best way to engage the workpiece material for a smooth entry and exit from the cut. Maintaining chip load and avoiding gouges are also important.”

On the other hand, using a 0.005-inch end mill poses special considerations. The effects of vibration are magnified when cutting with such a small cutting tool. Even the force of flood coolant can deflect a cutting tool of that diameter and degrade machining results.

“In this case, the CAM software gives me options for different toolpath strategies. Mastercam X has a new interface that makes it easier to evaluate which strategy looks the best and to check the results,” Mr. Krutt says.

A new area of exploration for Mr. Krutt is using high speed tool paths for machining his molds. “I don’t have a specialized high speed machine,” Krutt says, “so I had been avoiding them, thinking that since I didn’t have a high speed mill, they didn’t apply to me.” Recently, however, his experience with high speed tool paths has been revealing. “High speed motion is actually beneficial on a conventional three-axis machine,” he says. “The whole point is to eliminate sharp moves and create extremely smooth entry and exit motion—that makes it ideal for my work,” he adds. Mr. Krutt points out that the smooth motion is excellent for his delicate tooling, helping to avoid breakage that can occur with traditional machining strategies.

As an example, Mr. Krutt recently programmed a part using high speed “area clearance,” a smooth, non-angular tool path that cuts from the outside in, but automatically switches to inside out if it encounters a pocket. The result, says Mr. Krutt, is both efficient and safe for his tooling.

Another area that Mr. Krutt is eager to exploit is Mastercam’s feed rate optimization. This technique constantly adjusts the feed of the tool path based on the material removal rate, thus maintaining a constant chip load. Mr. Krutt says that this will let him run his machine more efficiently. “The real benefit is that by combining my experience and these new toolpath strategies, I feel confident that I’ve greatly reduced the risk of tool breakage.”

Driven By The Product

Being a product-line manufacturer largely determines the competitive pressures and opportunities that Branchline Trains must respond to in its machining area. “We don’t earn our money by machining,” Mr. Krutt explains. “It’s the sales of our quality models that generate profits.” It is not necessary to run his machining center full time every shift. However, when mold components need to be completed, running overnight with no operator present is a big boost to timeliness and productivity. It also allows Mr. Krutt to attend to his responsibilities as a general production manager.

“In a small company like ours, each of us has to fulfill several job functions,” Mr. Schneider says, explaining this division of labor. Mr. Schneider provides the instinct and passion for model railroading (he got into the hobby as a young child). Before helping start Branchline Trains, Mr. Schneider acquired a background in the graphic arts, so he handles the intricacies of decorating railroad models in accurate paint schemes, lettering and railroad logos. This background also prepared him to design and produce the company’s product catalogs, kit box designs, labeling, instruction sheets and advertising. Meanwhile, Mr. Krutt’s flair for mastering the facility’s diverse production equipment provides the perfect complementary skills on the manufacturing side.

Because Mr. Krutt supervises most production tasks, being a full-time programmer and machinist isn’t feasible. That is why maximizing the machining center’s productivity is critical. Here again, the new version of the CAM software enables him to run in the unattended mode more readily. “The key is knowing that the NC program won’t break the cutting tool in the first 10 minutes after the lights are out but will finish the job so it’s ready the next morning,” he says.

Using the verification feature lets him view anticipated results and make adjustments quickly by using the backplot slider to find the lines in the program that need to be modified. Checking depths of step-downs, for example, has become a habit for Mr. Krutt.

That said, he admits that the kind of machining he does often calls for test cuts and experimentation. “There’s no comprehensive or reliable source for machining parameters when cutting with very small cutting tools and complex geometry,” he says. Testing speeds and feeds to see which give the optimum results is the best way to learn.

Occasionally, Mr. Krutt asks his cutting tool supplier for custom-ground end mills with extra long flutes. “Standard tools have a three-to-one length to diameter ratio, but I may need the extra length for deeper pockets. This company can grind these specials for my application, but the right speeds and feed and toolpath strategies can’t be found in any handbook,” he adds.

A Fun Business

It’s clear that Branchline Trains is more than a business. Mr. Schneider’s love for the hobby keeps inspiring him to look for new products that will be popular with his fellow model railroaders. He notes that the overall level of quality and variety in model railroad kits has never been higher than it is today. New standards for detail and authenticity are being set all the time. That keeps the shopfloor challenge for Mr. Krutt exciting and compelling, a part of the business that he finds especially rewarding.

For people building layouts and collecting train cars and engines, one of the popular slogans is, “Model railroading is fun.” That spirit isn’t lost on either Mr. Krutt or Mr. Schneider at Branchline Trains.

Related Content

Custom PCD Tools Extend Shop’s Tool Life Upward of Ten Times

Adopting PCD tooling has extended FT Precision’s tool life from days to months — and the test drill is still going strong.

Read MoreHigh-Feed Machining Dominates Cutting Tool Event

At its New Product Rollout, Ingersoll showcased a number of options for high-feed machining, demonstrating the strategy’s growing footprint in the industry.

Read MoreForm Tapping Improves Tool Life, Costs

Moving from cut tapping to form tapping for a notable application cut tooling costs at Siemens Energy and increased tool life a hundredfold.

Read MoreOrthopedic Event Discusses Manufacturing Strategies

At the seminar, representatives from multiple companies discussed strategies for making orthopedic devices accurately and efficiently.

Read MoreRead Next

Setting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More