Grinding Carbide--A Niche Within A Niche

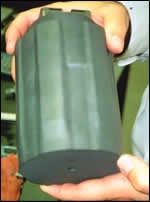

If one must pick a manufacturing specialty, grinding carbide might not be the first choice because it’s perceived to be very difficult. RPM Carbide Die, however, has worked the material for nearly 40 years and, as specializing seems increasingly to be the order of the day, this northern Ohio shop is in a good position to thrive.

Share

It seems that in today’s manufacturing environment, consultants to metalworking shops (and trade magazine editors) would be virtually speechless if the word “niche” were to suddenly disappear from our vocabulary. It’s touted everywhere. Metalworking businesses are advised, cajoled, directed and told from every direction to find a niche in order to survive.

Of course, niche manufacturing is only one of many operating strategies for shops trying to find ways to successfully deal with the changing landscape of domestic manufacturing. But regardless of the strategy chosen, success is in the tactical execution. Any strategy can only be as good as the shop is at making it happen.

Long before the current ballyhoo of finding niche markets descended on metalworking shops, RPM Carbide Die, Inc. (Arcadia, Ohio) found its specialty. In 1967, this shop started up grinding carbide.

And after almost 40 years, it’s a niche the company continues to get better at by continuously improving its capability through the implementation of better machine tool technology and ever more precision-driven processing knowledge. The carbide manufacturing specialty has also become a platform for other niches that the company has successfully ventured into including hard turning and milling of steel, cutting exotic metals and ceramics for aerospace, and even cryogenic treatment of cutting tools.

Learning New Tricks

A willingness to try new things is a hallmark of most job shops. Without an innate curiosity about how to do things, most job shops would fail because of the nature of the business. Every job that crosses the shop’s threshold is new and requires a facile mind to approach its profitable processing.

At RPM, curiosity is part of the shop culture. It stems from the company’s founder, Walter Metcalfe, and is embodied in his son, Eric, who is president of the company.

The company’s hard-earned expertise in working with carbide triggered a natural migration into working with other difficult materials. Tool steels, exotic aerospace materials and ceramics are now part of the RPM process proficiency portfolio.

“Most of our machinists would rather grind carbide than steel,” says Eric Metcalfe. “They find it easier to process; the surface finishes are nicer; size is easier to hold; dwells are better; it’s more predictable than steel. Getting steel off the grinders is what led us to hard turning.”

An implementation pattern developed as the company moved into new areas of manufacturing. “When we looked to expand our capabilities beyond grinding carbide,” says Mr. Metcalfe, “we first acquired the best tools we could. An example was our move into hard turning. We purchased CNC turning equipment and, after a short learning curve, the turning department was cranking out parts at very high efficiency levels. The key for hard turning and other process additions was to give the employees the right tools and let them do what they know how to do.” RPM turns only tool steel with hardness from 60 to 70 Rc. The shop uses CBN inserts for all of its hard turning operations.

This pattern, using current technology as a base for process expansion, was repeated in the EDM department, hard milling department and multi-processing (turn/mill) departments. The result for the business was an increased base of capability for the shop to go after a wider market and a solid base of expertise in a wider range of processes.

“We took our core competency of grinding carbide and parlayed it to other materials and processes. This greatly expanded our capability as a job shop to offer more to our existing customers, and it helps us acquire new ones,” recalls Mr. Metcalfe.

Re-Learning Old Tricks

Any business that is growing its capacity, as RPM did while implementing and optimizing its expanded capability, must juggle resource allocation. “As we worked to get our new departments up, running and contributing,” says Mr. Metcalfe, “the flagship carbide grinding department continued doing its excellent work with little technological attention from the company. We felt if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.”

Most of the company’s highest-skilled employees were working in the grinding department, and although they were using the company’s least advanced equipment—mostly manual grinders—the work got out the door. However, after evaluating the efficiency of the new departments, based in large part on the newer technology that was installed, grinding was now the company’s least efficient department.

In 2000, RPM invested in new grinding technology. The company purchased a Studer CNC grinder to address the technology gap that had arisen in the grinding department. The machine’s ability to profile grind under programmed control was a large technology leap from the manual machines used at RPM.

Like the pattern in the other departments, it soon became clear to the “old hands” that this new CNC grinding machine had advantages. They could not only increase the efficiency and throughput over the older manual machines, but there were some operations the machine could do that previously required secondary operation such as EDM to pull off.

During 2001, the shop experienced its first business downturn in 11 years. “We reduced our employment and took the opportunity to re-evaluate how we were manufacturing,” says Mr. Metcalfe. “Like many shops, when business is good, the goal is to get the work out the door. There simply isn’t time to look at efficiency.”

The recession gave RPM time to look closely at its flagship process of grinding. “We thought we knew everything about grinding hard materials,” recalls Mr. Metcalfe. “But the capability of the new CNC technology we saw from these grinders made us look hard at what we thought we knew.”

In 2002, RPM purchased around $1 million in equipment for the shop. That equipment was focused not only on capacity but also on efficiency. In 2002, sales were down from the record year of 2000, but the shop was more profitable. “Last year we put out very close to the same amount of work, dollar-wise, as 2000, but with 20 percent fewer people.

“Initially, we looked at areas of the business where new technology could be quickly and successfully installed,” says Mr. Metcalfe. “For example, we bought a new CNC EDM sinker. We had one already, and adding the second doubled our capacity but allowed one operator run both machines, so our labor increase was zero.”

Re-Learning Grinding

Once CNC grinding hit the shop floor, it was like going back to grinding school—not because the collective knowledge in the shop was made obsolete but because the advances in machine and wheel technology from the shop’s old manuals to the new Studers allowed for a dramatic increase in what was possible. “We thought we knew all about grinding,” says Mr. Metcalfe. “We’re still learning.”

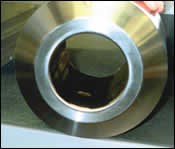

Profile or single-point grinding is perhaps the biggest advantage that RPM enjoys with its new grinding machine technology. The ability to follow a programmed contour on the OD or ID has dramatically improved the throughput of complicated dies that RPM makes for numerous industries. Depending on the amount of stock removal required, RPM will sometimes use a combination of form wheel and single point. “If we’re removing a lot of material,” says Mr. Metcalfe, “we’ll rough with a form wheel and finish with the single point. Profiling a heavy cut makes the cycle time too long.”

Wheel technology has also positively impacted RPM’s productivity and efficiency in grinding carbide. “We have recently started switching from resin bond diamond and CBN wheels to vitrified wheels,” says Mr. Metcalfe. “That change alone has given a 10 times improvement in metal removal rates. With resin bond, we ran a 100- to 120-grit wheel for roughing. With vitrified, we rough with a 150- to 180-grit wheel, which gives us better surface finish, even with the more aggressive metal removal.

The vitrified bond holds the diamond better than resin wheel and has larger gaps between the grit and bond. That’s equivalent to chip clearance on a single-point cutting tool. We have also learned that the vitrified wheel performs best during aggressive cutting. If you baby the vitrified wheel, it will load up quicker than if you run it hard. We used to leave finish pass stock of 0.001 inch and then let the resin wheel dwell out. It seemed like it never did completely dwell out. With the vitrified, you dial in 0.001 inch, go in and cut it. Because of the harder bond, there is little dwell with these wheels.”

The downside of vitrified wheels is the expense. RPM recently ordered a set of vitrified wheels for its new Studer grinder, a CBN and diamond rougher, and a diamond micro-finish wheel for about $14,000. However, the shop has yet to wear out its first diamond wheel.

“We use both resin and vitrified wheels in the shop,” says Mr. Metcalfe. “The resin wheel gives the workpiece a more mirror-like finish than does the vitrified wheel. The resin actually burnishes the carbide, and some of our customers specify the highly polished finish.”

That Guru Is You

The key to RPM’s success in its niche of grinding carbide is its quest to do a better, more efficient job. Even after 40 years of processing carbide and other hard materials, the shop still looks upon itself as learning about how to grind.

There are no single-source gurus for manufacturers, especially in a specialty process such as grinding and a niche within the niche of grinding carbide. Seeking out technology partners such as its machine tool supplier and wheel supplier, RPM avails itself of their respective expertise and then parlays those technologies into useful shopfloor practice.

“It’s all about making better parts for the customer more efficiently so we can remain competitive,” says Mr. Metcalfe. “We know we don’t know everything about the technology available for grinding carbide. We must seek good technology providers who can teach us what we don’t know.”

That’s good advice for any manufacturer.

Related Content

The Future of High Feed Milling in Modern Manufacturing

Achieve higher metal removal rates and enhanced predictability with ISCAR’s advanced high-feed milling tools — optimized for today’s competitive global market.

Read MoreOrthopedic Event Discusses Manufacturing Strategies

At the seminar, representatives from multiple companies discussed strategies for making orthopedic devices accurately and efficiently.

Read MoreHow to Determine the Currently Active Work Offset Number

Determining the currently active work offset number is practical when the program zero point is changing between workpieces in a production run.

Read MoreInside the Premium Machine Shop Making Fasteners

AMPG can’t help but take risks — its management doesn’t know how to run machines. But these risks have enabled it to become a runaway success in its market.

Read MoreRead Next

Registration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)