Getting Centered With Centerless

A job shop that specializes in cylindrical grinding is shifting more of its work from ID/OD grinders to centerless grinders. In understanding the rationale behind this move, other shops can determine where centerless makes the most sense.

Share

ECi Software Solutions, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Autodesk, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

High-precision grinding is not exactly for the faint of heart. By the time a part arrives at a grinding shop, it has undergone milling, turning, heat treating and other operations. Each completed process adds value to the part, and each may have taken longer than expected. That hurriedness, coupled with nano-level roundness requirements, is enough to make even Type-B personalities at grinding shops panic. Compounding those pressures is competition from other effective technologies. Yet, John Shegda, owner of Hatboro, Pennsylvania-based M&S Grinding is calm and collected. That’s because amid the virtual extinction of “low hanging fruit” jobs and competition from hard turning, his shop is thriving. In fact, it has tripled in size since last year and is looking to upgrade more of its equipment.

Much of the shop’s recent success can be attributed to proper allocation—that is, knowing when to invoke the powers of the latest centerless grinding technologies for its cylindrical work and when to employ other methods. To aggressively seek out higher precision work and become more profitable, it has shifted jobs that might normally be associated with OD/ID to its newly acquired infeed/throughfeed grinders. In doing so, this grinding subcontractor not only demonstrates where centerless is most effective, but also what centerless grinding is capable of today.

Not Your Daily Grind

The misperception that high-precision grinding involves possessing superhuman strengths is perpetuated by a lack of understanding of the dynamics of the process. Mr. Shegda rejects this notion of “black magic” grinding that keeps this accessible technology from being maximized. He and his staff of 14 apply more logic and resourcefulness than sorcery to this form of grinding. They draw upon the expansive analytical skills and grinding knowledge passed down by Meron Shegda, who started the business in 1957. Since 1990, his sons John Shegda and Mark Shegda have run M&S. Meron Shegda was an avid checkers player, and his zest for the game helped him hone analytical skills that would prove useful when he founded the family business.

“We owe everything that we have done and everything that we know to our father,” John Shegda says. “He was one of the smartest men I’ve ever known.”

These days, the small- to medium-sized boutique operation relies on inquisitive, nimble minds and nimble equipment in the form of a mix of CNC, automatic and manual machines. The scope of its work encompasses all forms of cylindrical grinding, primarily for the medical and aerospace industries, for which M&S can grind multiple steps, angles, tapers and radii of almost any configuration. Its client base of about 500 includes many machine shops, some of which contract with M&S to correct out-of-roundness specs on a fast turnaround basis.

Having long since recognized the effectiveness of centerless grinding technology, M&S applies it eagerly these days. In fact, centerless grinding affords the shop the confidence to seek out and successfully complete work with extremely tight roundness and dimensional tolerance restrictions.

Accomplishing complex and difficult work under demanding circumstances is part of the thrill for Mr. Shegda and his staff. These high-precision jobs usually range in size from one to 10,000 pieces, and typically have tight roundness and concentricity requirements, which can be as low as 20 millionths.

“Most of the new work we perform is either very tight tolerance for diameter/roundness (generally aircraft industry components) or some kind of crazy, small configuration for the medical industry,” Mr. Shegda explains.

Finesse And Fundamentals

The centerless grinding process itself lays groundwork for success for this type of work. That’s why M&S defers to this method whenever possible.

“Foremost, centerless is faster,” Mr. Shegda explains. “The process itself is generally more accurate because the machine doesn’t have to move in such a small increment. Thus, we can control tolerances to a greater extent.”

One differentiating factor between centerless grinding and other cylindrical grinding processes is that the workpiece is not mechanically constrained. OD machines typically clutch the work between centers or in a chuck and rotate the workpiece against the grinding wheel, whereas centerless grinders contain no “centers” with which to clasp the workpiece. Centerless instead relies on the successful interactions

among its three key components—the grinding wheel, the regulating wheel and the workblade.

During the centerless process, the workblade supports the workpiece on its own outer diameter. This workblade is located between a high speed grinding wheel and a slower speed regulating wheel with a smaller diameter. To achieve rounding action, for instance, the workblade must be arranged in such a way that the centerline of the workpiece is above the centerline of the grinding and regulating wheels.

About 2 years ago, the shop made a strategic capital investment to refine and push the limits of the centerless process. The shop acquired a Monza 410 CNC throughfeed centerless grinder. Prior to that point, only remanufactured centerless machines—six of them to be exact—occupied the shop floor. Although the remanufactured grinders routinely hold 0.0001-inch tolerances, it was not possible for M&S to efficiently reach the super strict tolerances dictated by a swarm of demanding medical and aerospace jobs with them. To grow its high-precision work even more, the shop later added a Monza 310 infeed grinder for machining headed pins, headed spools and tiny medical parts down to 0.020 inch in diameter.

“If we had to ‘fight’ with the machine on roundness, straightness or on diameter size, then we would not effectively be able to handle this demanding, high-end work,” Mr. Shegda comments. “The Monza machines have allowed us a tighter level of control of the geometric features of the part for this work, and so have made the work less complicated to do.”

“Work of this nature is still not easy by any means,” he continues. “But at least we can concentrate on the problem that the parts themselves are presenting instead of dealing with limitations of the equipment.”

For the shop, part of new grinders’ value is that they facilitate swift setups. In fact, an operator can often set up basic centerless jobs in 15 to 20 minutes, though an elaborate job can sometimes require hours—without indicating. Being able to set up jobs on both the older machines and Monzas quickly is especially crucial for M&S, as it might break down and set up six to eight times per day, per machine.

“Given the nature of our work and the constant setups that go along with that, it is just not feasible for us to spend an hour on each to get it right,” Mr. Shegda says.

Instead of relying heavily on finesse, M&S can let its Monza 410 throughfeed do the brunt of the work. Equipped with a “correction plus” feature, the machine allows the operator to initiate on-the-fly adjustments, pertaining to correcting the diameter size and so on.

Roundness, the type and the condition of the wheel and the amount of material that needs to be removed are all factors that influence setups as well. The reason Mr. Shegda wanted a throughfeed machine was to be able to “backup” the size when a tight job is in-process.

“The worst thing you can do for sizing consistency is stop a throughfeed centerless process,” Mr. Shegda explains. “By being able to increment effectively to 0.00001 inch (10 millionths), we can control size tightly on the Monza 410 without stopping the run.”

In addition to understanding the fundamentals of centerless and appreciating the equipment needed to carry out the process properly, shop personnel must also understand proper allocation, which ultimately impacts profits and overall efficacy of operations.

Even though the shop deems OD grinding as the best means by which to achieve roundness between 10 to 20 millionths while accurately holding features relative to other features, this method is not a match for all of its incoming jobs. Mr. Shegda finds that customers often mistakenly think that they need to grind between centers, when in fact they need the capabilities of centerless. OD grinding can be problematic for parts with high length-to-diameter ratios, for example.

“When a part is long and skinny, an OD grinder may struggle,” Mr. Shegda explains. “By contrast, the centerless machine doesn’t really care. A 0.250-inch diameter part that is 10 inches long and has a 0.0001-inch total OD tolerance would be a nightmare on an OD grinder. However, we can process it much more simply on a throughfeed centerless or even on a large infeed machine if the part has a head on it. The key is that the part is supported on three sides: the carbide blade underneath, the regulating wheel on one side and the grinding wheel on the other. As long as all of the supporting surfaces are true, then theoretically, you can grind ‘dead’ straight without too much trouble. Of course, theory is much different than actual practice, but if you really know what you are doing, very tight tolerances are achievable.”

This shop’s quest for more challenging grinding work indicates the general need to compete against hard turning. The chief competition this shop sees to centerless grinding does not come from other grinding shops—there is plenty of work to go around—but, rather from other competing technologies.

“We consider hard turning as ‘the competition’ because shops can now efficiently turn 0.0005 inch and tighter in many cases on heat-treated steel,” Mr. Shegda explains. “This has actually led to shifting our focus to fussier, more challenging work to grow the business.”

“Right now, only those capable of high-precision, high-quality work and being responsive and trying disruptive technologies are succeeding,” he continues.

Mr. Shegda follows his own advice. Earlier this year, his shop implemented a disruptive technology—a medical guide wire grinder, which is, for lack of a better expression, a cross between a Swiss screw machine and a centerless grinder.

Related Content

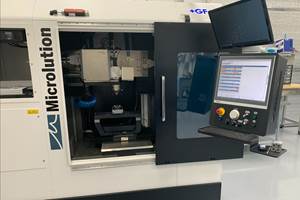

Where Micro-Laser Machining Is the Focus

A company that was once a consulting firm has become a successful micro-laser machine shop producing complex parts and features that most traditional CNC shops cannot machine.

Read MoreHow to Mitigate Chatter to Boost Machining Rates

There are usually better solutions to chatter than just reducing the feed rate. Through vibration analysis, the chatter problem can be solved, enabling much higher metal removal rates, better quality and longer tool life.

Read MoreHow to Determine the Currently Active Work Offset Number

Determining the currently active work offset number is practical when the program zero point is changing between workpieces in a production run.

Read MoreInside the Premium Machine Shop Making Fasteners

AMPG can’t help but take risks — its management doesn’t know how to run machines. But these risks have enabled it to become a runaway success in its market.

Read MoreRead Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.png;maxWidth=150)