Everything Changes

Through a sweeping transition to high speed machining, a Maryland contract shop realizes its goal of same-day, "in by 9, out by 5" turnaround.

Share

Don Swart remembers the first words he said after the presentation was done. The presentation’s topic was high speed machining—specifically, high speed machining for small production parts like his. Mr. Swart’s shop had long been pushing toward same-day service, with the goal of “in by 9, out by 5” for customers’ critical parts. Now, he could imagine the machining process that would make that goal a reality. There was just one catch, and it was a really big catch.

“I’ve got to change everything,” he said.

Everything.

That is, Mr. Swart would have to change every significant aspect of his shop’s existing process—a process that, by most measures, was already performing well. Installing new machine tools would only be the beginning.

More Than The Machines

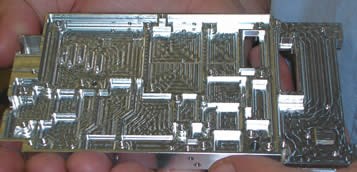

Mr. Swart manages the machine shop for Metlfab. This Frederick, Maryland, manufacturer provides machined aluminum components and other parts to customers in the communications industry. The presentation that changed the machine shop manager’s thinking about how to mill these parts was given by machine tool supplier Mikron. It involved machining centers that would allow the shop to machine its particular parts not at the 10,000 or 15,000 rpm to which it was accustomed, but instead at speeds of 30,000 to 36,000 rpm. Cycle times could be cut in half, while quality would either stay the same or get better. With this kind of performance on the shop floor, the shop would be able to receive a CAD file in the morning and ship the finished parts in the afternoon—literally “in by 9, out by 5” turnaround.

The problem was, the commitment would involve replacing the shop’s current machining centers with 10 new machines. Those 10 machines would replace 20, but the investment still was large—and buying machines was just the most straightforward step. In addition to making this investment, the shop would also have to…

-- Abandon horizontals, because the precision high speed machines were verticals.

-- Abandon tombstones as part of the switch to verticals, and therefore abandon the practice of machining many pieces in one cycle. Instead, the shop would need a workholding method for quick loading of single pieces and quick change-over from job to job. In part, the shop invented this workholding itself.

-- Abandon all sense of speeds and feeds. The parameters that make sense at 30,000 rpm are entirely different from the parameters the Metlfab machinists were used to applying. The shop used trial-and-error to find these faster parameters, because they don’t appear in any handbook the shop has found.

-- Abandon the rough/finish mindset. The high speed machines make it possible to both hog out material and achieve final tolerances using the same end mill. Indeed, the machines are at their best when used this way.

-- Feed the machines. No longer could the machinists think in terms of one job at a time. To keep the machines productive, they would prep many jobs simultaneously.

-- Program for production. Finally, the shop had to abandon its previous CAM system. It was too slow. The company needed a CAM system that would let its programmers provide tool paths to the shop floor quickly enough to keep up with the much faster process.

The transition took about 18 months, Mr. Swart says. Metlfab made all of the above changes, with 13 months of working in stages to get all of the equipment in place, followed by another 5 months before the shop had learned how to use the equipment effectively enough to realize its potential.

All along the way, there was one process component that could not be abandoned. This was the most vital component of all—the one not named in the list above, but implied in every item. That is, the people.

The enthusiasm of the 22 members of the machine shop staff would determine the success of the new process. The question was how to persuade these people that radical changes—changes affecting each of them on every working day—were the right changes to make.

Mr. Swart found his answer to that question in one word: airfare. He took his staff members on a trip, showing them the same level of confidence that the company had shown to him.

Letting Go

Fortunately, one critical member of the company did not have to be convinced. Orlan Helmick, Metlfab’s owner, was ready to invest in a better process. Mr. Swart describes him as someone who looks at sophisticated production equipment and finds within it the unseen potential for small-batch production. Most batch sizes for this shop currently run 20 pieces or less, most lead times are 3 days or less, and the shop is feeling pressure to accommodate smaller numbers in both categories. At the same time, the range of part numbers is getting bigger, as customers aggressively introduce new products. Aware of all of these trends, Mr. Helmick has long been pushing the “in by 9, out by 5” idea, with Metlfab making a major change to its equipment every few years to move closer to that goal. This time, however, the shop made nearly a clean sweep, leaping the rest of the way to the goal by reinventing its process.

Mr. Swart even had the next incremental solution in mind before he discovered the full possibilities of much higher spindle speeds in this application. That solution involved horizontal machining centers and a different machine tool supplier, but he was hesitating to commit.

“You’re not satisfied, are you?” Mr. Helmick asked him. Mr. Swart said no.

Therefore, to the owner, the right decision was clear. He encouraged his employee to let go of his plan, let go of all of the legwork that had led to this plan and begin the search again. This new search is what brought Mr. Swart to the Mikron machines, the reinvented process and the dramatically higher speeds.

Faith And Confidence

A vital component of this search was the two men’s faith, says Mr. Swart. Both he and Mr. Helmick are Christians, and prayer figured significantly into their deliberations over the shop. Mr. Swart says that God guided the decision they made, and faith in God therefore gave the men confidence that the sweeping change to the process could be made successfully.

There were others to persuade, however. In fact, the two men knew that persuasion would be as key to the success of the process as any engineering. The new process would require all of the machine shop staff members to release old habits and old expectations in favor of new approaches to setting up, pacing their work and organizing their days. With this in mind, Mr. Swart traveled with a group of the more senior shopfloor personnel to Mikron’s office in Holliston, Massachusetts (its U.S. headquarters is in Lincolnshire, Illinois), so that a larger number of Metlfab employees could see the presentation he had seen.

The night after the group saw this presentation, there were many questions back at the hotel, and Mr. Swart says the answer to nearly every question was “yes.” Can we change our fixturing? Can we re-think our tooling? Can we use balanced toolholders? Yes, yes and yes, Mr. Swart told them. Metlfab wanted to offer “in by 9, out by 5” production, and it was ready to make the investments.

That conversation proved to be the beginning of a particular change in outlook at the shop. Employees at Metlfab had always faced “hot” jobs, but in the past they viewed these jobs with dread. Urgent orders often could not be accommodated within normal working hours, so production schedules had to be disrupted and employees had to work unscheduled time. Now, employees realize that they oversee a new, special process that has the power to accommodate urgent requests without significantly disrupting regular work. “Hot” jobs have become welcome challenges, because they reveal what the process can do. Employees still watch the clock, Mr. Swart says, but now they don’t watch it with distress as the deadline ticks closer. Instead, they watch the clock with a sense of accomplishment, gaging just how fast and responsive their shop has become.

Starting with the machines, some of the important ingredients of that process are described under the headings below.

The Machining Centers (One Ingredient)

Metlfab now has five Mikron HSM800 machining centers and five of the company’s HSM600U “ProdMod” machines. The latter machines have rotary axes that Metlfab uses for 3+2 machining, as well as tool capacity of 170 and a ring of 14 pallets on each machine. All 10 machines have 36,000-rpm spindles and X-axis travel of 800 mm.

Standardization

Relying on machines from one builder makes the process more flexible. The commonality means that every operator can run any machine, and any job has a number of machines available to run it.

To build on this advantage—that is, to make the machining centers even more interchangeable—Metlfab standardizes the machines’ tooling. Each of the ProdMod machines has 145 tools that are the same from machine to machine. Only the remaining 25 tool positions are available for the use of special tooling—something Metlfab now tries very hard to avoid.

Fewer Tools

Speed makes this tool standardization possible. The high spindle speed permits high feed rates, and the high feed rates allow a single small tool to perform a much larger range of work. A small-diameter end mill not only can rough out a pocket efficiently—eliminating the need for a large roughing tool—but it can also perform helical milling efficiently, machining a range of hole sizes to eliminate various drills. Doing more with fewer tools in this way reduces the number of tools that have to be stocked and set up, and saves cycle time by reducing tool changes. It also increases quality because the consistent tool diameter provides more uniform blends in the floors of pockets.

Even so, sometimes there is still a tool change between rough and finish. The old paradigm of roughing and finishing continues in cases where there is a critical surface finish requirement, but with an important difference: the same type of tool now does both steps. Specifically, a worn 12-mm end mill may hog out the material, while a new and sharp 12-mm end mill makes the final passes. After this sharp tool has run a few parts in this way, it then becomes the roughing tool for subsequent work.

Parameters

Metlfab uses Seco-Jabro end mills supplied by Seco-Tesco (Hayes, Virginia). The tooling is designed for milling at high speeds and feed rates. Mr. Swart says the design of the tools helps with the vertical machine configuration, because the flutes pull chips out of the machined pocket and out of the way of machining. In addition, Seco-Tesco is knowledgeable about high speed machining, and has been valuable to Metlfab in supplying speeds, feed rates and depths of cut. From the perspective of Metlfab’s conventional machining experience, the much higher feeds and much lighter depths used in high speed machining are counter-intuitive.

That said, even the parameters from this knowledgeable source are only starting points. The shop still has to experiment to find what works best for its own particular parts, setups and cycles. The small variables that could affect the performance of a very rapid cut are numerous, so trial-and-error is essential for finding the best conditions. If a tool breaks, then that is a lesson for next time, with Metlfab noting the event and taking care to run that pass at a smaller depth of cut next time. In this way, over time, the shop is slowly building a knowledge base of what parameters work best for each tool. To ensure that this knowledge is applied, the shop continually updates the parameters that are assigned automatically out of the CAM system’s tool library.

Software

The shop’s new CAM system comes from Mastercam (Tolland, Connecticut). Metlfab needed a new system not just to generate programs faster, but also to meet the needs of faster machines.

The customizable tool library in Mastercam is an example of the features that now let Metlfab’s programmers feed NC files to the shop floor more quickly. Machining parameters are automatically applied, based on the shop’s latest understanding of the right cutting parameters for its tools. Further time savings come from the software’s ability to automatically update tool paths to reflect changes to details of the part. This latter capability is valuable because many new part numbers result from Metlfab’s customers simply making changes to existing designs.

Then there are the tool paths themselves. Mr. Swart says the shop’s previous system would not have let the shop mill at high speeds effectively. That system generated more simplistic paths with abrupt changes of direction. Preserving tool life at high feed rates requires more fluid tool paths with rounded corners and gradual transitions, something the new CAM system provides.

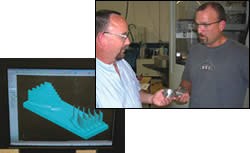

Workholding

Precision two-jaw chucks from Schunk (Morrisville, North Carolina) proved to be accurate enough that the shop could trust them to clamp work quickly without affecting the work’s position or orientation. Because the vertical machining centers generally machine just one part per cycle, the ability to rapidly load and unload parts is critical to the process’s success. With batches so small, quick setup of new part numbers is critical, too. Therefore, the shop uses the Schunk chucks to quickly and precisely clamp nearly all of the work that is run on the Mikron machines.

The jaws, however, are a Metlfab design. Most of the shop’s parts are machined from solid blocks, but there is a broad variation in block size. With reversible jaws that can quickly be alternated between standard and extended clamping surfaces (see photo on page 79), a single chuck can accommodate nearly the entire size range.

Cutting “32 Hours Per Day”

The standardized workholding, the generous number of pallets and the machining cycles that rely on a standardized set of cutting tools all have made it far easier for the shop to set up long queues of jobs for its machines. “In by 9, out by 5” is an important service, but not all jobs require it. For the ones with slightly longer lead times, the shop now realizes a greater return on its investment in machining capability by running unattended or lightly attended outside of the normal business hours.

In fact, the normal business hours are the least productive. The shop once conducted a study to determine how much production it achieved during the 8-hour day shift. The answer was 6.5 hours of production on a very good day and more like 4.5 hours on a typical day. By day, the new process does not improve that in-cut time. Indeed, the shop has now added to the distractions that occur during the day for the sake of making the more numerous nighttime hours productive.

Day shift employees now prepare jobs for a lightly attended 10-hour night shift that is staffed by only three employees. These employees are “basically on roller skates,” Mr. Swart says, moving from machine to machine after hours to keep them all cutting. These few night-shift personnel also finalize setups for other jobs, so that the shop can continue running without employees for 6 hours further. The result is 16 hours of continuous production per day, over and above what the day shift achieves.

And Mr. Swart says that 16-hour figure may understate the productivity. The high speed machining process delivers parts at a rate of output that the shop still considers high. The process is so fast that, “at the speeds and cycle times we were used to,” he says, “the production now is actually more like 32 hours per day.”

Related Content

How to Accelerate Robotic Deburring & Automated Material Removal

Pairing automation with air-driven motors that push cutting tool speeds up to 65,000 RPM with no duty cycle can dramatically improve throughput and improve finishing.

Read MoreRead Next

Cutting Tools For High Speed Milling Of Aluminum

Go with the flow—chip flow, that is. The uninterrupted flow of the soft aluminum chip determines the design of the end mills that Metlfab uses.

Read MoreSweet, Sweet Spot

For this aerospace job shop, harmonizing key aspects of each high speed machining process creates a "sweet spot" where productivity jumps. Harmonizing other key aspects of shop operations also creates a "sweet spot" that helps the company capitalize on this jump in machining productivity.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)