Share

When writing about a machine shop’s workholding solution that involves a cleverly designed 3D-printed box, the author’s path is lined with low-hanging puns. I will indulge just this once to get it out of my system: When engineers at Precision Metal Products (PMP) started thinking “inside the box” about 3D-printed tooling, the results were enough labor, time and cost savings to warrant a full explanation of what this shop achieved.

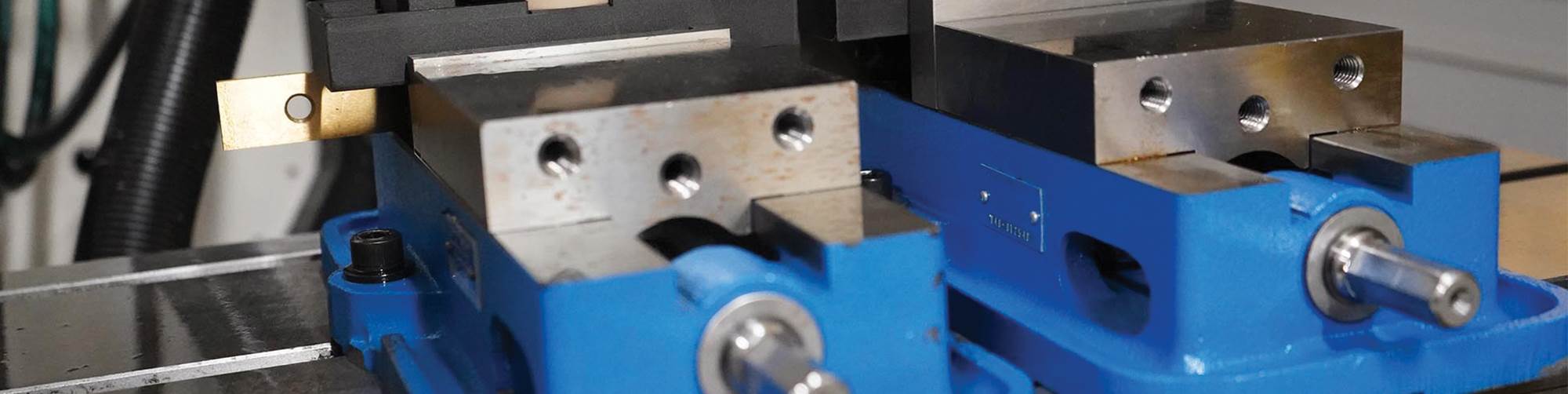

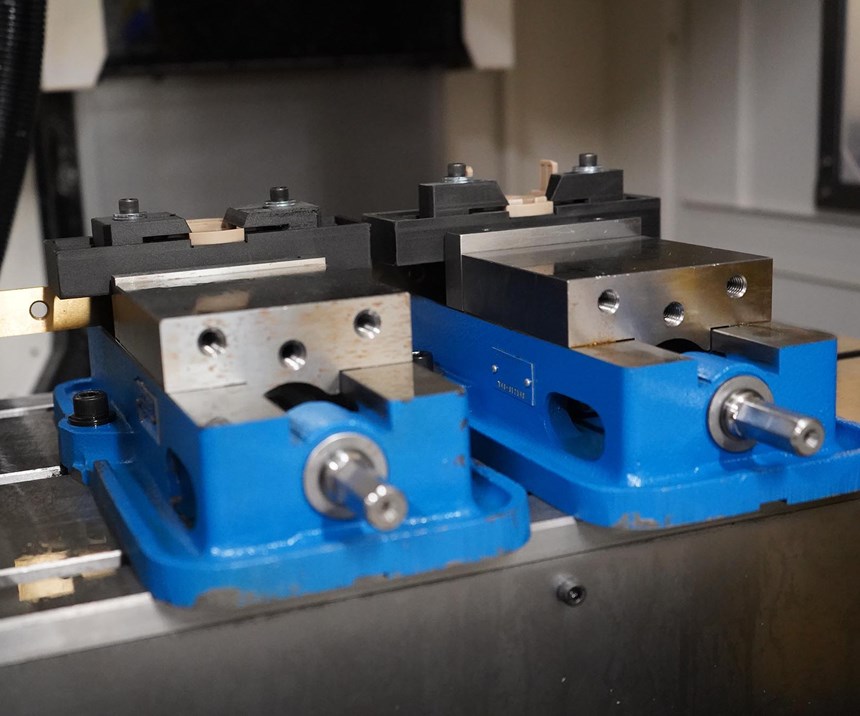

For 40 years, Milford, Connecticut-based PMP has served a range of industries, including medical, defense, microelectronics and commercial. Today the woman-owned shop has 135 employees and is certified to AS9100D, ISO 9001:2008 and ISO 13485:2003 standards, with core capabilities including CNC milling and turning, Swiss-type machining, metal stamping, wire electrical discharge machining (EDM) and light assembly work. PMP traditionally takes on high-volume contracts—a condition that stakes a premium on throughput and spindle uptime—especially for PMP’s variety of three- and four-axis CNC machining centers.

Like many shops, the bottleneck that PMP routinely encountered was centered around tooling, specifically the labor-intensive, costly and time-consuming process of creating custom workholding devices. From design to finish, PMP’s custom fixtures often required a week or longer to manufacture, all for a typically one-off part. “Thinking back now, that's how we had to do it," says PMP Project Engineer Rich Scanlon. “The engineer would get the drawing and then have to figure out the workholding method. Then I’d have to design it for manufacturing, buy the material, find all the clamps and hardware, and find the time for the toolmakers to fit it into their schedule. It took a long time to go from concept to reality.”

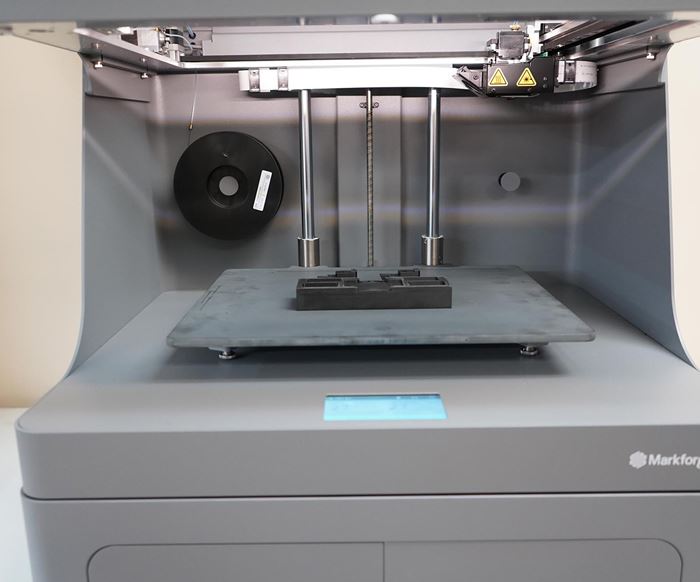

If you already have guessed how PMP bypassed this bottleneck, you might have read similar articles in this magazine about 3D printing as a solution for custom workholding challenges. But last fall, when the company purchased a Markforged X7 3D printer to address this problem, no one assumed that additive manufacturing could disrupt the status quo of its business operations.

Bypassing the Toolroom

In the fall of 2017, Mr. Scanlon and PMP Vice President Sean O’Brien attended an open house hosted by Methods Machine Tools, a Massachusetts-based supplier of machine tools and additive manufacturing equipment. As they arrived, the shop’s workholding bottleneck problem was front of mind. By the time Mr. O’Brien and Mr. Scanlon left the open house, they had come to a verbal agreement with Keith Carlisle, Methods’ additive and government sales and support manager, regarding the purchase of a Markforged X7: If Methods could create a few sample fixtures and parts that met the shop’s standards, consider the X7 sold. And it was.

More than a year later, the two men have integrated the X7 squarely into the company’s workflow for tooling and fixturing. Methods provided the initial training on the machine, which is capable of extruding 50-micron layer heights with plastics that are reinforced with carbon fiber, Kevlar or fiberglass—materials that have a higher strength-to-weight ratio than 6061 aluminum in some cases. PMP has been printing almost exclusively with a proprietary Markforged material called Onyx, a nylon thermoplastic infused with chopped carbon fiber.

In other words, 3D-printed material strength for tooling purposes has not been a top concern at PMP.

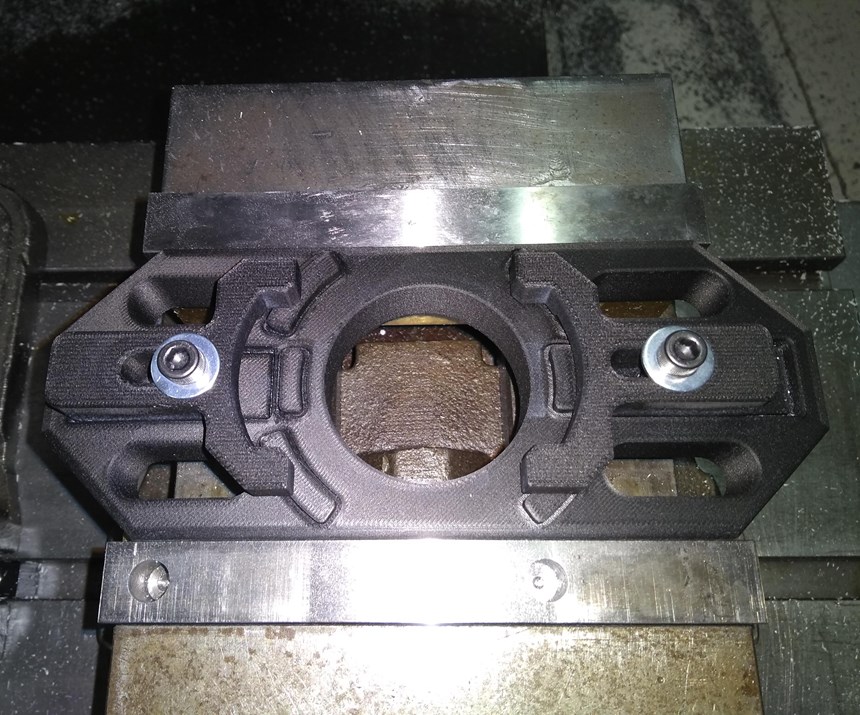

Instead, the biggest adjustments at the shop have centered around the design and workflow processes for tooling, namely, the adjustment of severing thought patterns around tooling from the constraints of the toolroom. Additive, Mr. Scanlon says, required “thinking outside of the normal way of doing things.” The process used to involve finding time on a toolmaker’s schedule to track down clamps and other hardware, then designing the piece for milling or grinding processes using machine tools that could otherwise be making parts.

The process is so different now that Mr. Scanlon laughs at the sound of it. “We use Pro Engineer to basically mold our design of the fixture over the part, draw up a couple of clamps and throw it over to the printer,” he says. “When I left work last Friday, I started a print on my way out the door. It’ll be ready for next week’s craziness by Monday morning.”

A Basket Case

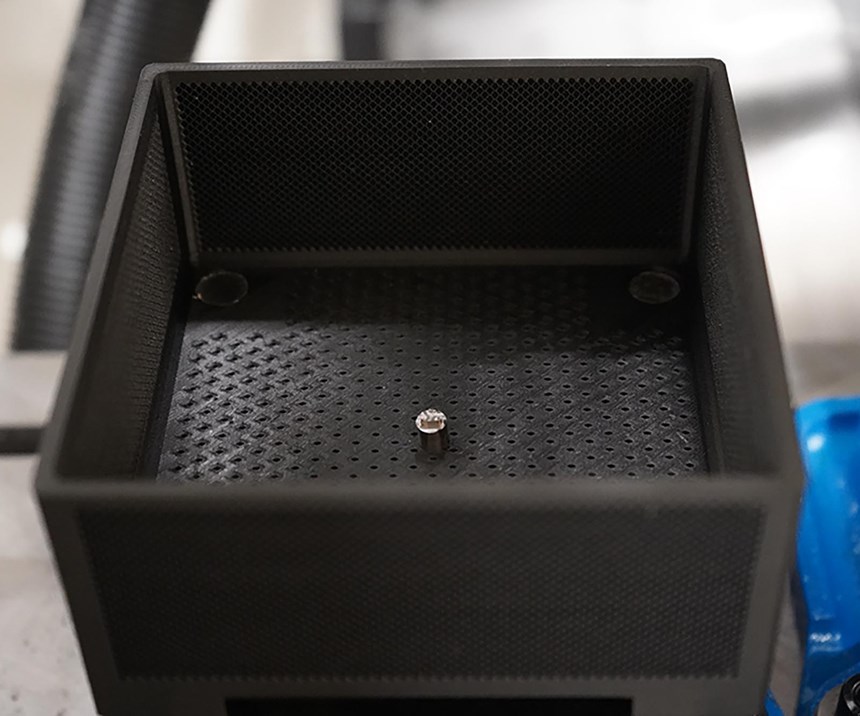

Here is what Mr. Scanlon means by “craziness.” PMP is a high-volume supplier of a round 17-4 stainless steel medical device that measures less than a tenth of an inch in diameter. The tooling for the workpiece, which itself is only 0.25-inch in diameter, was not much more difficult for the shop to create than tooling for larger workpieces: The process would have involved two or more setups, CNC programming, special fixturing and wire EDM. The challenge—the craziness—arose during the CNC machining process in which the force of the coolant would blast the part out of the vise and into the back of the machine.

The solution to this problem didn’t come in the form of 3D-printed soft jaws, but in a 5 by 5 by 3-inch 3D-printed box. Scanlon designed all five walls of the box (one side was left open) with a dense array of flood-coolant slots—hundreds of small triangles that form a screen to enable the coolant to flow through. The workpiece snaps vertically into a 0.5-inch hole located in the middle of the box, enabling the spindle to access all sides of the part within the confines of the box.

To keep the box itself secure, Mr. Scanlon printed an encasement in each lower corner to house a total of four magnets. Together, the magnets help secure the box to the metal vise. As machining takes place and as each part is cut free from the stock—five parts per slug—one by one the parts fall into the box, often attaching themselves to one of the four magnets that are fixed in the corner as the coolant evacuates through the flood slots.

The ability to additively manufacture tooling and fixtures has inspired this kind of “craziness” at numerous shops like PMP. But there, the benefits of 3D printing may inspire a foundational change to a core aspect of the shop’s business model.

Turning Down the Volume

Over its four-decade history, PMP typically has manufactured parts in mid- to high volumes. The greater flexibility with custom fixture lead times for high-volume production plays a large role in that decision—a decision that additive manufacturing is calling into question. The shop is seeing an uptick in requests for low-volume production work for the aerospace industry, work that the shop is in a much better position to accept today. “The ability to print your fixturing is key when you have high-mix, low-volume parts,” Mr. Scanlon says. “Instead of getting hung up making fixtures in the toolroom, now we just use our imagination, decide on the material and print what we need. That's been quite fun, and I suspect it represents a change around here.”

So far, the 3D-printed materials the shop has used are holding up for low-production work, including the box he created for the small medical device, which has performed well throughout dozens of operations. Because of that and similar custom workholding solutions he has created, PMP is getting parts to its customers “faster than anyone expected,” he says. “For the last short-run project we had to create fixtures, clamps and all kinds of items to be able to get that part to the customer faster. And we killed it. Now we’ve kind of let out the secret that we have this printing technology, and that’s helping us build customer confidence toward being able to achieve quick lead times.”

“As we go deeper into 3D printing, I’m sure it will be utilized more and more here,” Mr. O’Brien adds. The company is eyeing metal additive manufacturing technology to possibly bring in house, he says, and might make a decision on that front soon. For now, there is still untapped potential with the X7, including the benefits of custom-printed workholding that PMP is already creating. “We're still finding new ways to use the X7 nearly every week,” he says. “We’re continually having ‘aha’ moments and saying, ‘Let's try this.’ But even now, we feel like we’re way ahead of the game.”

Related Content

Five Common Mistakes Shops Make with ER Collets (And How to Prevent Them)

Collets play a crucial role in the machining process, so proper tool assembly and maintenance is important. Here are five potential pitfalls to avoid when using ER collets.

Read MoreThe Future of High Feed Milling in Modern Manufacturing

Achieve higher metal removal rates and enhanced predictability with ISCAR’s advanced high-feed milling tools — optimized for today’s competitive global market.

Read MoreHow to Accelerate Robotic Deburring & Automated Material Removal

Pairing automation with air-driven motors that push cutting tool speeds up to 65,000 RPM with no duty cycle can dramatically improve throughput and improve finishing.

Read MoreLean Approach to Automated Machine Tending Delivers Quicker Paths to Success

Almost any shop can automate at least some of its production, even in low-volume, high-mix applications. The key to getting started is finding the simplest solutions that fit your requirements. It helps to work with an automation partner that understands your needs.

Read MoreRead Next

Setting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read MoreBuilding Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)