Keep Your Coolant In Circulation

Retaining fluid can be good! Coolant recycling saves the shop both purchase and disposal costs. Here is a look at the service provided by one recycling contractor.

Share

The argument in favor of recycling used coolant comes down to dollars and cents. Coolant costs money to purchase, then costs additional money in the form of disposal fees to throw away. In short, it costs money coming and going. So when recycling can upgrade old, rank coolant into fresh and reusable coolant that would otherwise have to be purchased new, then this "environmentally friendly" effort may also be beneficial in a more directly meaningful way—by saving the shop money on a potentially significant source of expense.

One contractor providing this service is Fluid Recycling Services, based in Livonia, Michigan. The company primarily recycles coolant, but also recycles washer fluid, cutting oil, and hydraulic oil. In the case of each of these fluids, the recycling process—as well as the rationale—is essentially the same.

The company performs much of its work via "mobile recycling units." These are trucks that visit customer facilities, bringing heaters, centrifuges, and other equipment necessary for removing fluid contaminants. The company has trucks serving metalworking shops in the industrial Midwest and southeastern United States, as well as California and Ontario, Canada. In larger plants, the company also keeps employees on-site to monitor the coolant and coordinate recycling on the customer's behalf. And though a variety of savings can come from having a contracted specialist oversee coolant management in this way, the savings from coolant purchase and disposal costs are much easier to quantify.

Company account manager John Coyle notes that a shop's coolant replacement cost generally ranges from $0.20 to $1.20 per gallon, depending in part on the concentration used. Coolant disposal costs range from $0.10 to $0.90 per gallon. The determining factors here include the shop's location, how much competition there is among area industrial waste haulers, and the severity of the locally applicable regulations.

In general, says Mr. Coyle, coolant recycling is not cost-effective unless the shop or plant disposes of at least 1,000 gallons of coolant per month. However, as the shop's coolant use grows beyond this point, its margin for potential savings grows as well.

Quality Control

One example of a large user of recyclable fluids is the VarityKelsey-Hayes facility in Woodstock, Ontario. This plant, employing about 350, machines automotive brake rotors, brake drums, and wheel hubs. Before contracting with Fluid Recycling Services, the plant was disposing of about 120,000 combined gallons of coolant, washer fluid, and hydraulic fluid per year. Now, the purchase of both of the latter two fluids has been cut in half. And disposal of coolant is only five percent of what it once was.

Fluid Recycling Services keeps a small laboratory here, staffed by two of its employees during the day, and one at night. The lab takes multiple measurements from a coolant sample daily, to determine coolant acidity (pH level) and concentration, and check for the presence of microorganisms.

Plant engineering manager John Bond says this process is more scientific than the plant's previous coolant management system. Before the lab was established, line supervisors would make their own subjective decisions as to coolant quality.

"The supervisor would look at a sample in a refractometer, and decide from that whether the coolant needed an additive of some sort, or water, or more concentrate," Mr. Bond says.

The inevitable result of this was inconsistency in the coolant from one day to the next. This created the danger of a critical breakdown in the chemistry of the coolant, due to the cumulative effects of different daily adjustments.

"No one knew how they were changing the coolant's condition," he says. "Add too much of some additive, and you may alter the pH to a level where it affects the health of the operator or no longer provides good operating conditions. Add too little, and you may promote fungus or bacteria."

Today, the contractor holds the coolant to a more narrow range of parameters, because the lab's measurements allow technicians to work from more specific information. Some additives the plant once used to adjust the condition of the coolant on the fly have been eliminated. And when the condition of the coolant moves too far beyond an acceptable control limit, the lab personnel have it sent to the dirty coolant holding tank. Here it awaits the next visit from the recycling truck.

The Process

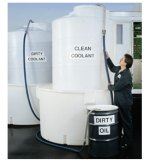

"Dirty" and "clean" holding tanks are features of all of Fluid Recycling Service's customers, whether or not the company also monitors the coolant on-site. A shop draws fresh coolant from the clean tank, while sending fluid from sump changes, drainage, or skimming into the dirty tank. The capacity of each tank is typically 1,000 to 3,000 gallons. In general, the capacity is chosen to provide enough supply to last between recycling visits scheduled once per month.

Coolant in the dirty tank can be contaminated with tramp oil, chips, metal fines, bacteria, mold, or all of the above. This coolant has lost its pastel color, and its fruity scent has been replaced by a sulfury smell more like rotten eggs. To make this fluid usable again, the technician in the mobile recycling unit sends it through a series of decontamination processes.

The first step is to skim off whatever tramp oil is floating on top of the dirty coolant tank. The recycling technician does this before bringing the coolant into the truck.

Once inside the vehicle, the coolant passes through a succession of strainers and graduated filters. The progression is designed to remove smaller and smaller chips, and other contaminants. Free of this large particulate, the fluid is then heated and pasteurized—like milk—to remove bacteria and mold. While the coolant is being heated, it is also spun; it passes through a centrifuge, which removes whatever tramp oil is left, as well as any metal fines that proved too small for the filters. The fluid is then cooled and routed to the clean tank. It is tested for concentration and purity, and supplemented with additional water, coolant concentrate, and/or biocide as needed. Thus the shop receives usable coolant, cleaned to those conditions agreed upon in the contract with the recycling service. The recycling technician leaves a written report of the latest fluid analysis after every visit.

The process is not waste-free. The tramp oil, for example, must be disposed of using a licensed waste hauler. There is also the solid waste from the filters, which may or may not require special handling. However, the combined disposal costs for these two byproducts should be tiny compared to the previous cost of disposing of this same material along with all of the coolant. A third byproduct of coolant recycling is the metal fines drawn out by the centrifuge. These can be added to whatever system the shop already has in place for recycling chips.

To Each His Own

Mr. Bond sees another advantage to fluid recycling beyond the cost savings. Because his plant keeps employees of the recycling contractor on-site, he is not required to think much about fluid management himself. Nor are any of the plant's employees.

"We no longer rely on our own refractometer readings; we don't have to," he says. "Instead, we focus on our specialty—machining brake parts—and let a different specialist worry about our coolant."

Read Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)