Defining Practice

Are you working on a hobby or are you training? Both involve practice.

Share

ECi Software Solutions, Inc.

Featured Content

View More

Takumi USA

Featured Content

View More

.png;maxWidth=45)

DMG MORI - Cincinnati

Featured Content

View More

My wife has been learning Japanese flower arranging (Ikebana) for years and now teaches her own classes. As teaching problems arise, we have discussions in which I have quite a bit to contribute from my experience training new hires, students and customers. It always surprises me how much metalworking and flower arranging have in common. I guess problem solving for creative endeavors is not specific to the endeavor.

In our last conversation about her “rookie” teaching problems, we discussed a situation in which one of her students became frustrated. She let her student create his arrangement, but when it came time for her to “correct it,” she had to tear it down almost completely. When she was finished, he agreed that it looked much nicer. However, he was frustrated that he could not repeat what she had done.

In short, we concluded that she needed to explain to her students the importance of practice and not look to her for technique for every situation. For example, her students needed to practice how to use a twig that curved versus one that is kinked. Early in the conversation, she thought I was “off my rocker” for thinking they somehow would not know the value of practice. She also could not comprehend how they would keep looking to her to prepare them for every color variation and geometric anomaly of flowers, greenery, branches and other natural material.

I explained to her that from my experience, people automatically place me as an authority when I am teaching. I have to tell them, or at least remind them, that I make mistakes and there are plenty of things I do not know. This is often greeted with an expression of, “You sound a bit like me.” Depending on the student, they are either satisfied or put out.

As we discussed it, my wife came around to the view that school, among other institutions in society, patterns our brains to look for teachers before using self-practice to solve problems and develop skills. Teachers are expected to know all and provide us with everything we need to know in any given situation. Do-it-yourselfers are labelled, often self-labelled, as amateurs.

An interesting snippet from the conversation was about our own perception of practice. We notice that if we enjoy practice, it is a hobby, pastime or interest. We do not feel like it is training, and the more time we can spend at it the better. It does not matter whether we have a teacher. With the lack of our knowledge working against us, we gain experience and insight, creating paths forward for ourselves. Many things go wrong when we just try things, but somehow, we find ways to deal with them effortlessly. This is actually practice and training, but it does not feel like it because we are patterned into thinking practice and training are hard and should have an element of boredom or at least onerousness.

If we dislike practice, it becomes grueling training that we perceive as pressed upon us. That is what real training is, isn’t it? The less time we can spend at it, the better, and there has to be a teacher for it or we simply will not do it. We tell ourselves we are stuck without someone to point us to the next objective. Great teachers make learning less painful.

For my son, hockey and piano lessons are examples of hobbies and training. One of the things that really tweaked my brain when thinking about my son is that practice and training is instilled almost dogmatically in sport and merely implied in school. For example, an athlete that makes it to a professional level expects that “getting there” means training harder and more seriously than ever in the past. I wonder how many other professions would benefit from this being patterned into general thinking. It seems that most people go through school with the opposite mindset. That is, once you graduate and bag a job, the training and hard work are finished.

When I look at my past, learning CAD, machining, CNC and CAM were all done informally and mainly on my own time. It was interesting, fun and frustrating at the same time but most importantly, I did not let the times when I lacked a teacher stop me from learning, doing and progressing. Basically, I tinkered my way through things when I did not have someone to guide me. In my 50s, I look back and see that I regimented my own practice, but back then I would have told you I was just goofing around, trying to figure something out.

While great teachers are still great teachers, at this point in my life I feel like some of my worst teachers were my best teachers. For instance, my “worst” teachers made learning unforgiving: If I didn’t learn, they didn’t care. It was up to me to care, to find a way to understand and practice on my own. When I lead training now, I find myself trying to be the worst teacher and not shoulder the responsibility of learning. That belongs to the student.

Students who train, practice and find their own paths are the ones who interest me anyway. I push them to understand the importance of trying things, to come up with three solutions instead of asking questions, etc. As a teacher, I have always believed that I merely create the opportunity for the students to learn. Now that I have a better definition of practice, I feel it is time to pattern their thinking with that, too.

About the Author

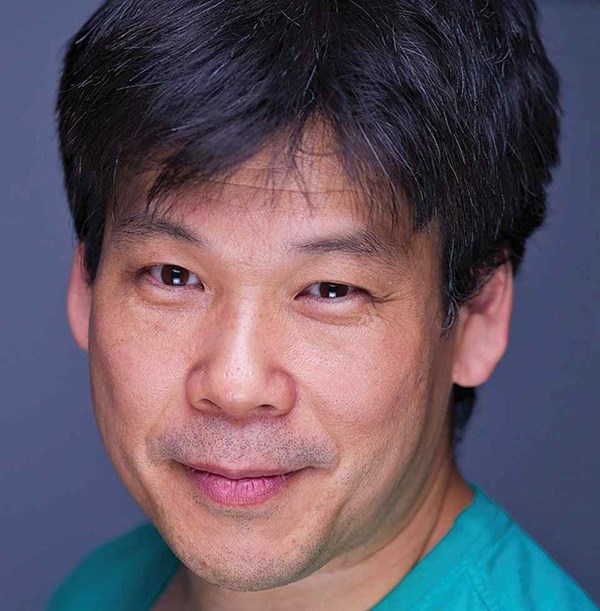

Kevin Saruwatari

Kevin is the owner of Qsine Corp., which was founded in 1968 by his late father, Mick. The custom machine design and manufacturing firm specializes in industrial product development, prototypes and short-run work. More at qsine.ca.

Related Content

How to Pass the Job Interview as an Employer

Job interviews are a two-way street. Follow these tips to make a good impression on your potential future workforce.

Read MoreIn Moldmaking, Mantle Process Addresses Lead Time and Talent Pool

A new process delivered through what looks like a standard machining center promises to streamline machining of injection mold cores and cavities and even answer the declining availability of toolmakers.

Read MoreAddressing the Manufacturing Labor Shortage Needs to Start Here

Student-run businesses focused on technical training for the trades are taking root across the U.S. Can we — should we — leverage their regional successes into a nationwide platform?

Read MoreFinding the Right Tools for a Turning Shop

Xcelicut is a startup shop that has grown thanks to the right machines, cutting tools, grants and other resources.

Read MoreRead Next

Building Out a Foundation for Student Machinists

Autodesk and Haas have teamed up to produce an introductory course for students that covers the basics of CAD, CAM and CNC while providing them with a portfolio part.

Read More5 Rules of Thumb for Buying CNC Machine Tools

Use these tips to carefully plan your machine tool purchases and to avoid regretting your decision later.

Read MoreRegistration Now Open for the Precision Machining Technology Show (PMTS) 2025

The precision machining industry’s premier event returns to Cleveland, OH, April 1-3.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)