Valtech Corp. manufactures mounting beams to hold these silicon ingots during the slicing, or wafering, process, before the silicon is further refined for use in smartphones and other electronics. The company uses older machine tools that have large work envelopes in order to run dozens of parts at once.

Of all the technology we overlook in our daily lives, the silicon chip still reigns supreme. If we bother to think about them at all, we consider silicon chips to be an ingredient, like wheat in bread, for electronics technology that is completely native to our environment.

Which is partly why a visit to the Valtech Corp. earlier this year — just before the world shut down — was so eye-opening. Valtech, which began in 1989 as a specialty chemical manufacturer of adhesives, molded polymers and aqueous detergents for the electronics industry, today is one of the country’s leading manufacturers of the ingot slicing beam — a single-use fixturing tool for various semiconductor materials in preparation for the slicing, or wafering, process.

A stack of mounting beams — single-use fixturing tool for various semiconductor materials such as silicon — produced by Valtech Corp.

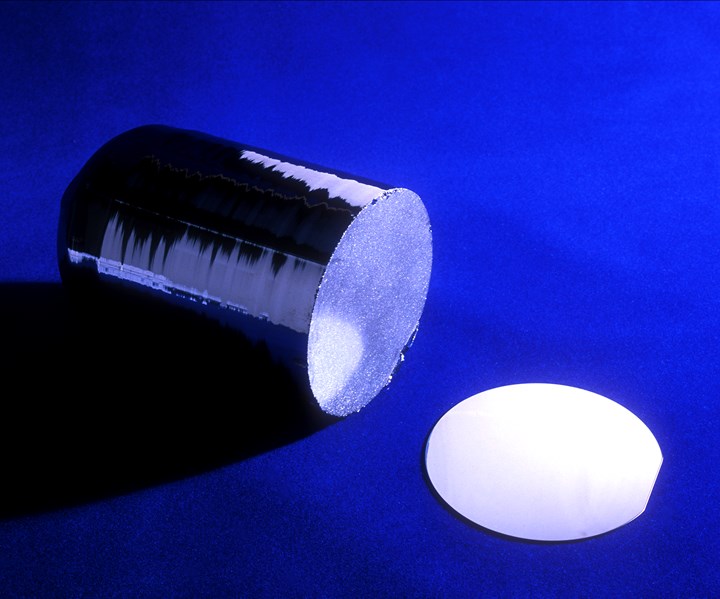

While the beams are relatively simple in shape, companies that manufacture silicon wafers use them to hold raw ingots of silicon or photovoltaic material as they are cut into thin wafers via slurry wire slicing, diamond wire slicing or ID saw slicing.

During the early aughts, Valtech, based in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, watched the ingot slicing beam side of its business slip away to foreign competition that continually undercut the company’s prices. Valtech had been molding its home-brewed slicing beams and sandblasting them to net shape — achieving mixed success at a significant cost, as only half of the product passed the company’s own QC processes.

Up against the wall when the Great Recession hit, one day a few of the company’s engineers began spit-balling an idea: Rather than molding and sandblasting, what if they over-mold the beams and machine them to net shape?

Ten years later, Valtech has a robust, lean CNC machining operation that the company has fine-tuned through a mix of continuous improvement and creative ingenuity. Beginning from the ground floor of CNC machining, Valtech has resourcefully outfitted its production facility with massive, older model machining centers — four Haas CAT40 HS2s and a CAT50 Kitamura HMC — that it uses to dry-machine up to 48 parts on a single tombstone with precise accuracy.

Every aspect of Valtech’s machining operations — from its extensive library of custom tools, to dust collection, to work planning, to creative solutions for ongoing maintenance — has helped the company reach automation-level production volume with used machine tools and a lean, nimble staff. Its product may be a niche, but the lessons that Valtech has learned while ramping up machining operations are universal.

Valtech’s row of Haas HS2 machining centers, older machines that the company uses because of the unusually large work envelope and X-axis travel.

The Design Is a Freak

The first two things to know about Valtech’s ingot slicing beams is that they are composed of the company’s proprietary catalyzed epoxy along with functional additives that kick up a lot of dust during machining, and that flatness is critical for finished parts. Valtech CEO Bob Girard says that the company’s transition from molding to net shape to machining was driven by yield requirements — requirements that molding and sandblasting lacked the precision to achieve. Mark Shumaker, now Valtech’s global plant engineer, initially joined the company to help expedite the epoxy mixing process and speed up overall production. But after experimenting with a Sharp vertical knee mill to prove out a machining process, Mr. Shumaker, Mr. Girard and others at the company became convinced that CNC machining was going to be the solution.

In 2010, Mr. Shumaker signed up for a CNC programming crash course offered by Haas. He began scouring the market for used machine tools, eventually buying the company’s first used Haas HS2RP — an HMC capable of 38-inch travel along the X axis — for 20 cents on the dollar. “Haas stopped making these in 2003, but most parts are still supported,” Mr. Shumaker says, “and you will not find a CAT40 pallet-changing horizontal with 500-millimeter pallets that has such huge spindle travel and a large work envelope. The design is a freak.”

Valtech worked with Chick Workholding Solutions Inc. to custom design and create two, four-sided tombstones as well as dual-station vises that can each hold up to six parts. The vastness of the work envelope also enables Mr. Shumaker to program CNC subroutines to run from 16 defined locations and make location-specific offset adjustments without editing the main program’s G code.

Valtech press operator Walter Snyder prepares to run 16 parts on a custom tombstone in the Haas HS2.

Based on its success with the first Haas, Valtech outfitted the production floor with three more HMCs — two additional Haas HS2s and a Kitamura, for parts that required larger tools.

Over time, Mr. Shumaker learned to design and produce custom-designed, lightweight fly cutter tools for the Haas machines that increased the range of part sizes each machine could handle. A few years ago, the company added another Haas HS2 — the shop floor’s fifth spindle — and Mr. Shumaker says that the team was able to increase output by 25% without adding additional labor.

Ask the Dust

The shop floor of Valtech is surprisingly clean for a room in which parts composed partially from talcum powder are dry-cut for 20 hours a day, five days a week. Valtech’s early experience using coolant found that the mess was worse — thick, ivory-colored mud instead of dry dust. Today while a centralized dust collection system keeps the ambient environment clean, conditions inside the machines are very different. Dust creeps into every nook and cranny. It covers every internal surface. Maintenance is critical and complicated.

“Even the Haas mechanics who would come out — and I am not trying to knock on Haas — but some of the guys would want to come here just to see these machines,” says Valtech’s shop supervisor Henry Zavala. “Because some of the technicians are younger guys who have never seen these models before. To them, seeing these machines is like being in a museum.”

Jeff Lance is Valtech’s maintenance engineer, CNC expert and original catalyst for the idea that CNC machines can produce the finished shapes. He’s also the man chiefly responsible for keeping the company’s machining equipment reliability at almost 90%. Mr. Lance says that the toughest issue he has faced was with the HS2’s tool changing system, which contained a critical flaw.

The Haas HS2 tool changer umbrella and several custom tools designed by Valtech engineer Mark Shumaker, including the fly cutter in position 19.

Turning the HS2’s huge carousel during tool changes requires heavy torque while the swing arm moves the umbrella in and out. Mr. Lance says that the entire system, weighing hundreds of pounds, was originally held together by a 0.8-inch set screw. “A little tiny set screw,” he says. “It was the only thing keeping that swing arm tight, which basically held the whole system. It has concentric cams on the rollers that roll out, and when it started banging and shifting, they would snap and then the entire thing would fall off inside the machine. It would take three of us to lift it out and put it back on.”

The solution? Completely redesign and rebuild the coupler as one component that connects the front end of the motor to the gearbox. “We drew it up, I gave it to Mark, he banged it out on his CAD system and handed it to our machine shop guys. We welded it in place and since then, it's never been a problem.”

The most pervasive issue when it comes to maintenance is the dust that results from dry-cutting the ingot beams. The dust naturally migrates to the bottom of the machines, but the constant back and forth Z motions also spread it to each corner and everywhere in between. The dust settles against servo motors. It knocks out switches. It creates maintenance headaches with anything less than constant upkeep.

The solution was a centralized dust-collection system, but that alone was not enough.

Dry machining in Valtech’s Mitsui Seiki HMC. The dust creates s different set of challenges than coolant.

The dust found its way into the machines’ steel way covers — into the accordion-shaped folds that trapped dust between each layer. Mr. Lance removed and replaced the steel covers with plastic covers made from common plastic tarps that he buys from his local hardware store. He hand-ties them together and installs them to the machine with tek screws. It costs next to nothing.

50 Parts to 500

“Walk with me,” Mr. Zavala says as we head across the shop floor toward an HS2. “The more I load up that spindle, the better it is for me, the better it is for the company, and the better it is for all of my guys. We can load a machine and walk away and do something else. Instead of having a tombstone come out every five minutes, ours stay in for hours.”

Mr. Zavala manages the five HMCs like a conductor, moving machine components between them to ensure that his philosophy — “the spindle needs to run” — rules the day. Any machine scheduled to run that has room for one more job is loaded with jaws out of an idle machine to max its capacity. It is not a groundbreaking strategy, Mr. Zavala says, it is a mindset. “So what happens?” he asks rhetorically. “By doing that over time, you become very flexible. You maintain balance.”

The precision needed to maintain parallel dimensions on the ingot beam grooves requires minimal deviation between the cutting tool diameters. The grooves cut into each beam need to stay within a couple of thousands of an inch parallel to each other, a fact that disallows the use of multiple inserts on any given cutting tool. Even minimal wear on one insert will result in variances outside of tolerance when a new insert is used. Instead, Mr. Zavala says that insert diameters need to be constantly measured and touched up to maintain consistency.

“If have to replace a tool, as soon as the machine stops, I jump right in, measure, get the offset numbers, touch off the end mill, pop it back in and keep it going,” he says. “Usually a tool change takes only three or four minutes and that's it. While my guy is loading the tombstone, I've already got the tool in, touched off and ready to run.”

Without betraying Mr. Shumaker’s age, it should be noted that he was well into the middle phase of his professional career when he attended his first CNC machining class. Over the course of 10 years, he has not only learned to program CNC machines and design custom tools for Valtech’s unique product, but also to look for efficiencies across the entire chain of operations for the company’s shop.

From left to right: Mark Shumaker, Brent Donaldson, Henry Zavala and Walter Snyder.

When Mr. Zavala noticed that the tool that cut the finish radius on one of the larger beams was only lasting 100 cycles inside the spindle, Mr. Shumaker modified the mold to make the part more compact. The result is that, with less material to cut, the cutter now lasts up to 140 cycles. Overall production efficiency also has drastically improved, from 50% first-pass quality to 95%. Staffing has gone from 30 employees to 20 as the number of HMCs has increased, all while the company has gone from making 50 different parts numbers per year to 500.

Mr. Shumaker and Valtech CEO Bob Girard believe that the potential exists to increase machining operations, which currently represent about 25% of the company’s bottom line, to a broader range of products and a more significant source of business.

“When we started to look at the results at the beginning of our machining experience, it was a ‘wow’ moment,” Mr. Girard says. “It changed the entire yield perspective for us overnight in a very competitive niche market. And the fact that we're able to do so much with so few people is one of the secrets to our being able to compete and win.”

Related Content

10 Lean Manufacturing Ideas for Machine Shops

In addition to the right mix of traditional strategies, a lean manufacturing toolkit can make high-mix, low-volume machining faster, more predictable and less expensive.

Read MoreRead Next

For Many Machining Facilities, the Mindset Now Must Be “Radical Automation”

What if there will never, ever be enough talent in your local labor pool to meet the still-growing demand for skilled manufacturing employees? The real challenge might lie in our expectations about how much skilled labor we need. Let IMTS 2018 be the beginning of facing this challenge.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)